On March 20, 2023, Ducks Unlimited Canada hosted a panel of wildlife and ecosystem experts in a one-hour webinar to celebrate bird migration, conservation and the official start of spring. The recording can be viewed online, and the following are 10 of our favourite FAQs and facts from the talk.

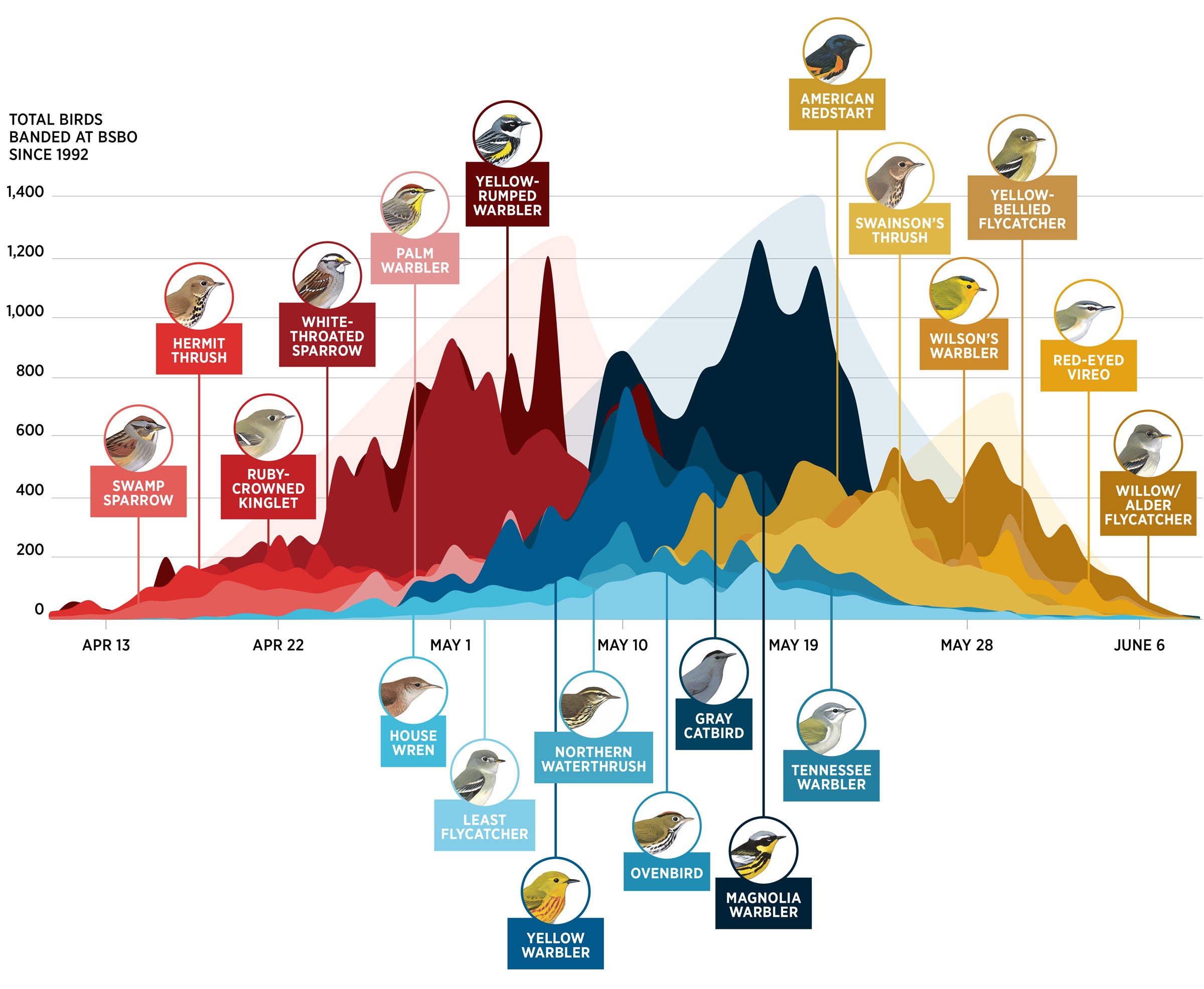

- What’s the best time of day for birding? Most migratory bird species migrate at night. For this reason, the best time of day to observe birds is often early morning, when the birds have completed their night flights and are landing to rest and feed. Paula Grieef, resident naturalist at the Harry J. Enns Wetland Discovery Centre at Oak Hammock Marsh, recommends the first hour or two after sunrise as prime time for birding.

- For some species with relatively risky migrations, young birds may take a different migration route than adults with migration experience. Erica Geldart, Motus coordinator and project specialist with Birds Canada, points to the example of the Ipswich sparrow. This species breeds exclusively on Sable Island in Nova Scotia and winters along North America’s Atlantic coast. Young Ipswich sparrows choose a safer but notably longer migration path than their adult counterparts, taking a detour to the mainland to avoid some of the longer ocean crossings on the way.

- Some birds can migrate extremely far distances without taking a break. The record holding bird species for non-stop active flight is the bar-tailed godwit. Many members of this shorebird species migrate between Alaska and New Zealand. They make a few stops along the way during spring migration, but in the fall they can fly more than 11,000 km without stopping, which can take up to 10 days.

- Why do birds migrate when it puts them at risk and requires lots of energy? James Paterson, research scientist at DUC’s Institute for Wetland and Waterfowl Research, says the most common reason is to access greater food availability. For example, birds that spend the summer in the boreal forest have access to millions of flying insects—but that food resource is temporary, and when the bugs disappear in the fall, the birds that rely on them need to find a reliable food source elsewhere.

- The observations you contribute to community science projects are full of potential to help biodiversity research and conservation. According to James Pagé, species at risk and biodiversity specialist with the Canadian Wildlife Federation, the data is also used by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) to help assess the conservation status of certain species. Recent examples of assessed species using community science data include the barn swallow, American bumblebee and grapple tail dragonfly.

How do birds find their way during migration? Migratory birds are good at navigating—some can even find their way back to exact locations from previous years. Depending on the species, they use a combination of cues like the position of the sun, the stars and magnetic fields (like a compass). They can also use visual cues like mountains as landmarks, to understand where they are in relation to the landscape. Just like people use highways, birds like ducks and geese often follow specific pathways—called flyways—to get from one area to another. Research using bird bands was used to define four migratory flyways in North America: Pacific, Central, Mississippi and Atlantic. These flyways have some overlap, and some bird species will use a different flyway to travel north in the spring than they take to fly south in the winter. We know that most birds migrate at night. But why do some birds migrate during the day? Some birds, like most of the soaring species (like vultures, eagles and hawks), take advantage of the warm air that rises from the ground during the day, to help them glide along their migratory routes.

Other species that are highly social rely on visual cues, and therefore daylight, to help keep their flocks together. Community science has been helping birds for a long time! The Christmas Bird Count, one of the longest standing community science initiatives, was started in 1900 by the Audubon Society, with 27 birders who recorded 90 species. The event is now run in Canada by Birds Canada, with tens of thousands of volunteers participating. In 2022, 3.5 million birds from 294 species were recorded at 473 individual counts in Canada alone. Migratory birds—along with other migratory species like dragonflies and pollinator species—pose a unique conservation challenge. These species rely on finding suitable habitat in multiple and distinct locations, for their breeding sites, migration stopovers, over-wintering and everything in between. The 2022 State of the Birds report shows ongoing declines in many migratory species’ populations—and their future relies on us to work across borders, taking a continental approach to habitat conservation.

Ready to learn more? Watch the recording of Nature’s Incredible Journeys for more facts and sign up for the DUC Migration Tracker project on iNaturalist today! Your observations will help raise awareness and support for the critical habitat migratory birds need to survive and to continue heralding the return of spring.