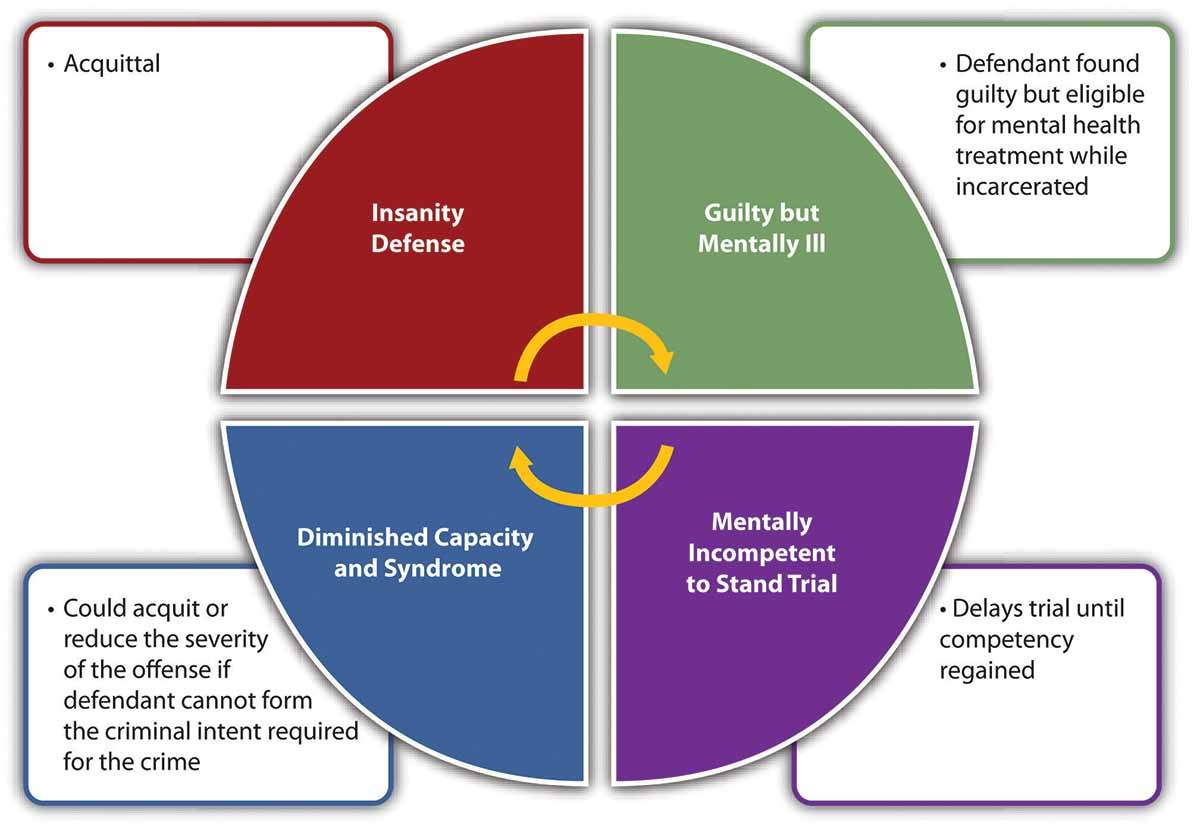

Thousands of crimes are committed every day, and most cases are “open-and-shut,” meaning there is little to dispute. The vast majority of criminal defendants plead guilty, typically facing undeniable evidence. Occasionally, however, a defendant tries to argue that they are not guilty by virtue of diminished mental capacity. This means that they are not guilty because a situation occurred that prevented them from knowing that the actions committed were wrong. Diminished mental capacity can be a mitigating factor in determining punishment or even allow a defendant to be found not guilty by reason of insanity. Here is a look at some controversial defenses arguing that the defendant had diminished capacity.

Setting the Stage: Mental Capacity & Guilt

The debate over what constitutes criminal guilt has raged since the dawn of human misbehavior. Today, mental capacity is the common term for one’s ability to understand the wrongness of one’s actions and control one’s behavior. However, both of these abilities exist on a spectrum in the real world due to the myriad of personality traits, intelligence quotients, and potential personality or mental health disorders experienced by individuals. Fortunately, the vast majority of people fit within a reasonable person standard in terms of their ability to understand the wrongness of actions and control their behavior.

But what of those who do not fit within the parameters of a “reasonable person?” In 1843, English courts began using the M’Naghten Rule. Daniel M’Naghten was found not guilty by reason of insanity, meaning he lacked the capacity to determine right from wrong. In the late 1800s, courts in the United States began using similar standards. In 1929, US courts began using the more expansive “irresistible impulse test” to acquit those who were, by reason of mental defect, unable to stop themselves from acting even if they knew their action was wrong. Periodically, new rules were refined for determining mental capacity and criminal culpability.

Setting the Stage: Temporary Insanity

The original “Twinkie Defense,” an umbrella term for an unconventional legal defense argument for diminished mental capacity, was temporary insanity. In popular media, ranging from books to television shows, criminals of horrible crimes are often depicted as trying to scheme their way out of conviction by pleading temporary insanity. The argument is often difficult, as “temporary” insanity means evidence is usually lacking after the fact. Almost always, this defense is used for violent “crimes of passion,” where the defendant was so enraged by a situation that they (allegedly) lost the ability to distinguish right from wrong and refrain from acting illegally.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Not surprisingly, the defense of temporary insanity has long been controversial, with people angered that someone who committed heinous acts is able to go unpunished. However, the defense is not usually successful. Sometimes, attempts to argue temporary insanity may be helpful to the defense in that they show the crime was not premeditated, which can reduce punishment. Some states allow a “middle ground” determination of guilty but mentally ill, where the convicted defendant receives mental health treatment either before or in conjunction with incarceration.

Historical Uses of Temporary Insanity Defense

In 1859, a congressman from New York named Daniel Sickles shot and killed an attorney who was allegedly having an affair with Sickles’ wife. Sickles was charismatic and popular and quickly won over the court of public opinion. Dramatically, Sickles’ legal team argued that the congressman was unable to control his passion, which made him not culpable for his actions. It was more generous than previous arguments of temporary insanity, such as those in England that required the defendant to have the capacity of a “wild beast.” Sickles’ defense argued that he retained his higher functioning but was so outraged at the immoral actions afoot that he could not stop himself.

Sickles was quickly acquitted and later served as an officer during the US Civil War (1861-65). Another famous acquittal under the insanity defense went to John Hinckley Jr., the attempted assassin of US President Ronald Reagan in 1981. However, because Hinckley’s insanity was not temporary, he was remanded to a mental hospital for treatment and was only released in 2022. Hinckley’s acquittal and avoidance of prison were controversial at the time, with many viewing insanity defenses as false attempts to pretend mental incapacity.

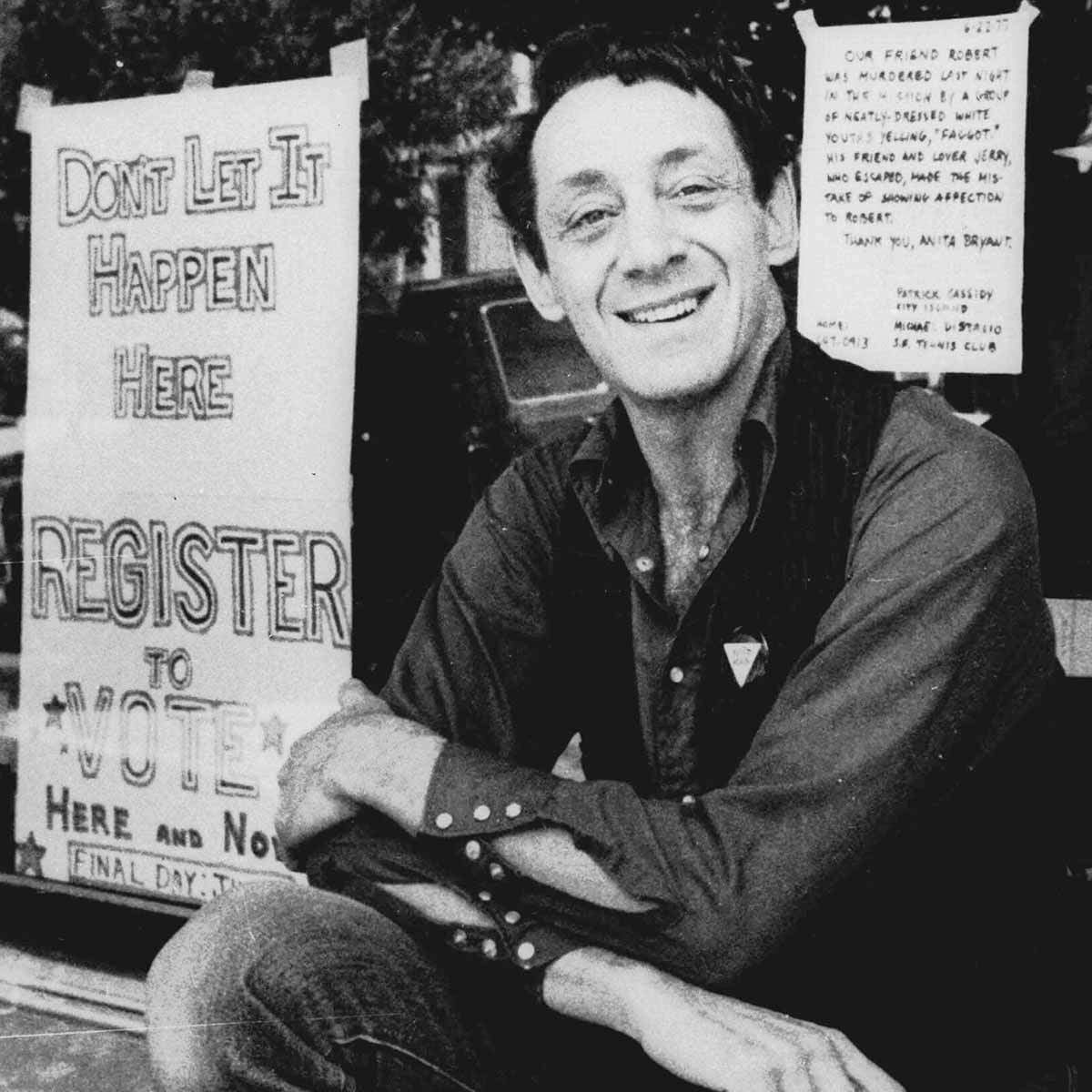

1979: The Twinkie Defense

The term “Twinkie defense” comes from the seemingly outrageous argument offered by the defense of Dan White, the San Francisco politician who shot and killed his former colleague, Harvey Milk, and the city’s mayor in November 1978. Milk was the first openly gay elected official in the United States. After killing mayor George Moscone, White went to the other end of the building and killed Milk, allegedly committing both murders in revenge for losing his seat as a city supervisor. White quickly surrendered to police officers afterward, leaving little question as to whether he had committed the murders.

White’s defense alleged that he had diminished capacity due to depression and mental illness, with these conditions being caused by his excessive consumption of junk food…such as Twinkies. A popular misconception is that White’s team alleged that the sugar itself caused White’s behavior, while the link is actually less direct. The jury agreed that White’s mental state did reduce his capacity and convicted him of voluntary manslaughter rather than murder. This resulted in outrage among the LGBTQ community; many felt that White’s seven-year sentence was insufficient. Shortly after being released from prison, White committed suicide in 1985.

1998: Gay Panic Defense

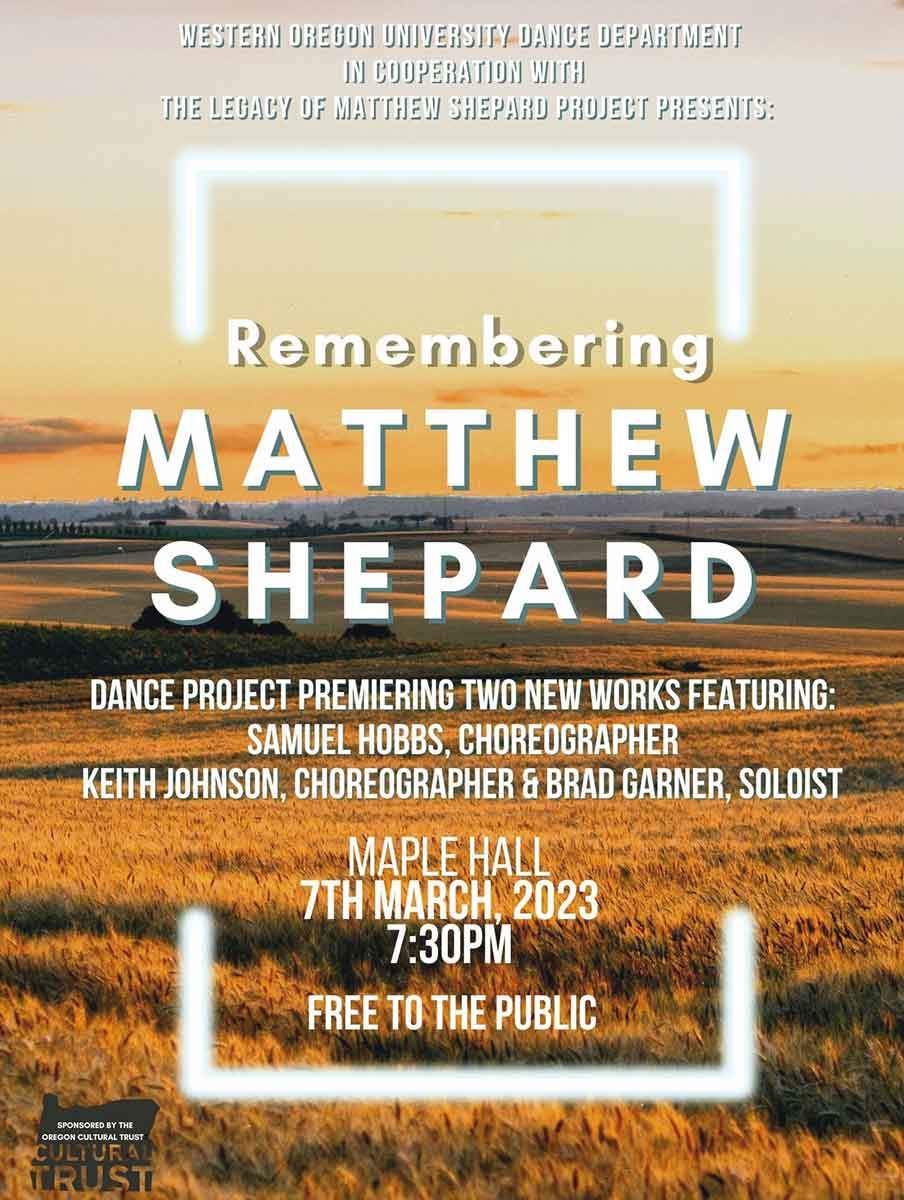

Another controversial criminal defense that has been considered a “Twinkie defense” is the gay panic defense and other iterations of it, such as the trans panic defense. This term stems from the trial after the 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard, a gay man in Wyoming. Shepard was beaten and left for dead near Laramie, Wyoming, his body tied to a fence. The two defendants originally alleged that they had reacted in a “panic” after Shepard allegedly came onto them. The trial judge rejected this defense, and some state legislatures have banned its consideration in court.

Despite claiming that they had acted in “self-defense” after being confronted with homosexual advances, the two defendants’ statements indicated that they had intended to rob Shepard. In the years after the murder, Colorado, California, and Illinois banned the use of the gay panic defense, followed by several others after 2017. Legislation to expand this ban is pending as of 2023 in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. As of 2017, iterations of the gay panic defense had been used in about half of US states, though they were typically unsuccessful.

2010s: “Affluenza” Defense(s)

In 2013, a Texas teenager killed four people while driving under the influence of alcohol. Instead of receiving a substantial prison sentence, as was expected by many observers in the tough-on-crime state, the teen received two years in a counseling program and probation. The teen’s lawyers successfully argued that the young man had diminished capacity to understand consequences due to “affluenza,” or a lifestyle of wealth and little discipline. Unsurprisingly, the public was outraged. Many equated it with preferential treatment for wealthy defendants, similar to white-collar criminals who received little punishment for financial crimes like embezzlement and fraud.

The 2013 intoxication manslaughter case was followed quickly by other alleged examples of “affluenza defenses,” typically arguing that the defendant would do poorly in prison and that imprisonment would destroy a promising future. The latter argument has controversially been applied to college athletes, with sexual assaults committed by male college athletes often considered a hidden epidemic. Star athletes accused of crimes may be defended with arguments that equate their highly competitive and risk-taking natures with diminished capacity for understanding boundaries and consequences.

Bad Science for Prosecution: Phrenology

But it’s not just defendants who have a penchant for using (alleged) pseudoscience: prosecutors and law enforcement have also dabbled in dubious data to provide “evidence” of guilt. Phrenology was a popular science in the 1800s that studied the link between physical characteristics, often of the head and skull, and behavior. Criminologists thought crime could be predicted, as those with certain physical characteristics would be more likely to commit it. The most famous proponent of this school was Cesare Lombroso, an Italian theorist who studied the alleged hereditary nature of criminality.

Despite the science being quickly discredited, phrenologists did bring about some positive ideas, such as the goal of rehabilitating and reforming criminals rather than simply punishing them harshly (as was common in the early 1800s). However, this “progressive” view often came with much paternalistic discrimination and stereotyping. Social Darwinists of the 1800s and early 1900s believed that many groups and cultures were less fit to engage in civilized government than others and extended this view to criminality as well. Many felt that people from poorer countries and demographics were more naturally suited to criminality, creating and reinforcing harmful stereotypes.

While physical traits were often discounted as a sign of criminality by the 1900s, authorities began to use new technology to try to measure defendants’ internal conditions. In the 1920s, the polygraph, often called the lie detector test, was invented. Polygraph machines did not detect lies but rather simply reported changes in bodily functions like respiration and heart rate. However, observers would use this real-time data to interpret that a tested subject was being deceptive. Polygraphs are typically inadmissible in court and cannot be used by private employers, though they may be used by law enforcement agencies to screen – and deny employment to – applicants. Many critics argue that polygraphs can both be “beaten” by very calm defendants and can give false positives of guilt to stressed and nervous defendants.

In the 1960s, the discovery of the XYY chromosomal anomaly, where males have an extra Y chromosome, renewed interest in the biological influence on crime. Both researchers and defense attorneys took to the new XYY discovery, with some wanting to test masculine-looking men for an additional Y chromosome so they could be monitored for aggression and defense attorneys arguing that XYY syndrome meant their clients were less culpable for their actions. Ultimately, research revealed little link between XYY syndrome and criminal aggression.

Highly Technical Defenses & Bench Trials

Both “Twinkie defenses” and highly technical evidence may confuse jurors, leading certain defendants to seek a bench trial rather than a jury trial. In a bench trial, the judge decides guilt rather than a jury. This can be advantageous to the defense when a case is highly complex, such as those involving temporary insanity or diminished capacity. A judge is more likely than a layperson to understand the complex evidence and its proper relationship to the law. Additionally, a judge is more likely to be dispassionate (unbiased) and rule based strictly on the evidence and the law rather than on emotion or public opinion.

Many defendants who choose a bench trial do so in order not to risk an angry jury. This often includes cases of temporary insanity or reduced mental capacity in the commission of violent crime. The jury may become inflamed and more prone to vote guilty based simply on the nature of the crime and media commentary, which would include media criticism of supposed “Twinkie Defenses.” Thus, even legitimate uses of defenses that seem implausible could backfire when subject to the decisions of lay jurors.

The success of “Twinkie Defenses” is often embroiled in the constant debate over bias and discrimination in the justice system. From crimes being reported from arrest to determining guilt to sentencing, suspects and defendants who are of the dominant groups in society, plus those who are physically attractive, are advantaged. Critics of the judicial system argue that poor and minority defendants are rarely given lesser sentences or acquitted on the grounds of mental incapacity, despite wealthy and white defendants often receiving such benefits.

One point of contention is access to mental health experts to testify on behalf of defendants. Although the US Supreme Court has ruled that indigent (low-income) defendants must be given a court-appointed mental health practitioner if one is requested, wealthy defendants are far more likely to have a psychiatrist testify to their incapacity at trial. Privately hired psychiatrists are more likely to actively assist the defense in making a defendant appear mentally incapacitated at the time of the crime, thus making wealthy defendants more likely to receive lesser punishments on the grounds of being less culpable for their actions. Therefore, “Twinkie Defenses,” at least successful ones, are only likely to be attempted by wealthier defendants.