New discoveries from dinosaur fossils show that in Canada millions of years ago, meat-eating dinosaurs hunted smaller plant-eating dinosaurs.

According to Reuters news agency, scientists on December 8 reported unearthing the fossil of a young Gorgosaurus dinosaur – about 5-7 years old – with a length of 4.5 meters. In particular, this fossil has its stomach intact, preserving its last meal.

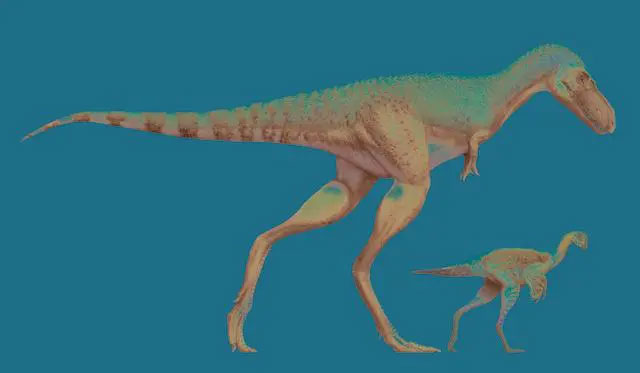

The Gorgosaurus dinosaur belongs to the same genus of carnivorous tyrant dinosaurs as the famous T-Rex that existed several million years later. Gorgosaurus walked on two legs, had short arms with two-fingered hands, and a giant skull 1 meter long. Full body length up to 9-10m and weight 2-3 tons.

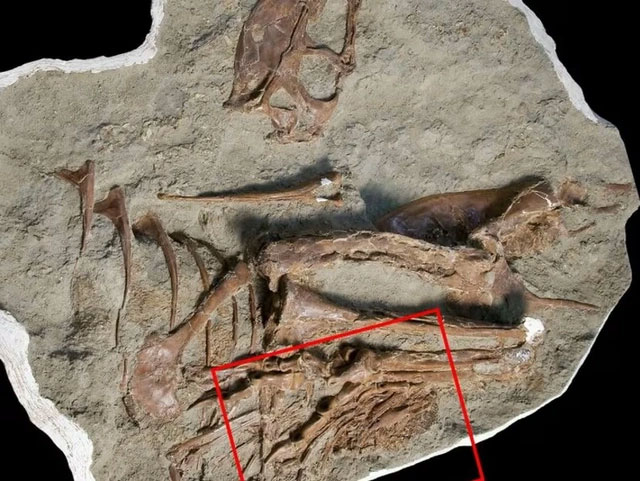

Prey remains intact in the stomach of a dinosaur fossil. (Photo: Reuters).

Prey remains intact in the stomach of a dinosaur fossil. (Photo: Reuters).

Gorgosaurus had a huge prey base and so could also be picky about its meals. 75 million years ago, in what is now the province of Alberta – Canada, they chose a plant-eating dinosaur named Citipes, with feathers and the size of a turkey, as prey.

Fossils show that Gorgosaurus cut up and ate only the legs of Citipes , ignoring the rest of the meat. The predicted reason is because the prey was too big to swallow whole, so this Gorgosaurus chose the meatiest part to eat.

Based on tooth marks left on prey bones, it can be concluded that adult Gorgosaurus could hunt dinosaurs even larger than Citipes.

The fossil was unearthed at Dinosaur Park in southern Alberta province – Canada. This area during the Cretaceous period was a forested coastal plain, near the western shore of a vast inland sea that divided North America in half.

This is the first tyrannosaur fossil with prey intact in its stomach.

Size difference between a Gorgosaurus and a Citipes. (Photo: Reuters).

Size difference between a Gorgosaurus and a Citipes. (Photo: Reuters).

This newly unearthed fossil has provided deeper information about the ecology of this dinosaur genus. It can be seen how the foraging and diet of tyrannosaurs changed significantly throughout their life cycle.

A study published in the journal Science Advances led by François Therrien, curator of dinosaur paleontology at the Royal Tyrrell Museum (Canada), has shown that different species within the tyrannosaur genus occupied maintain different ecological circuits at different times in the life cycle. This means that young tyrannosaurs did not need to compete with adults for prey.