From the Constitutional Convention onward, the issue of slavery was hotly contested. Southern states relied on this brutal institution to grow and harvest cash crops like cotton and tobacco. In the early 1800s, the expansion of slavery into new territories prompted political battles between abolitionists and supporters of slavery. The election of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln as president in 1860 led the South to secede and form its own country, the Confederate States of America. After the devastating American Civil War, one of the first industrialized wars in human history, the Confederacy lay defeated. The victorious Union, also known as the North, had to figure out how to reunite the country and protect newly-freed formerly enslaved people.

The Political Situation in the 1850s

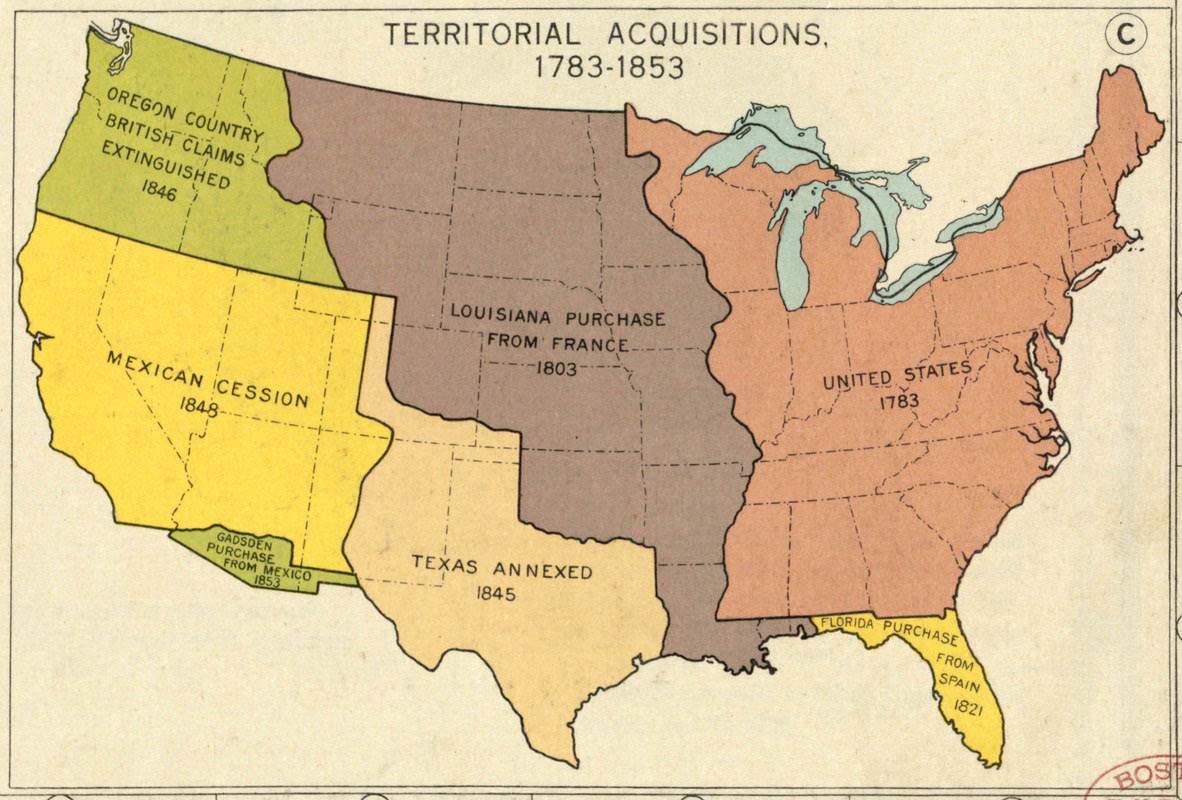

In 1848, the US emerged victorious in the Mexican-American War (1846-48). The Mexican Cession granted the United States vast amounts of territory between Texas–which became a state in 1845 and prompted the war–and the Pacific Ocean. Immediately, debates raged about whether this new territory would allow slavery. The South, which ranged from Texas to Florida and up to Virginia, allowed slavery. The North, which spanned from Maryland up to Canada, did not.

Slavery was controversial for many reasons, and many Americans opposed it for its moral and ethical violations. However, the South clung firmly to the institution, insisting it needed free labor to grow and harvest cash crops like cotton and tobacco. In the early 1800s, as the North industrialized and urbanized during the Industrial Revolution era, a social, cultural, and political divide grew between the two regions. Compromises were continually made to keep the peace between the North and South, with the Compromise of 1850 disallowing slavery in the new territory won from Mexico…but cementing it as a permanent institution within the United States.

1860: The South Decides to Secede

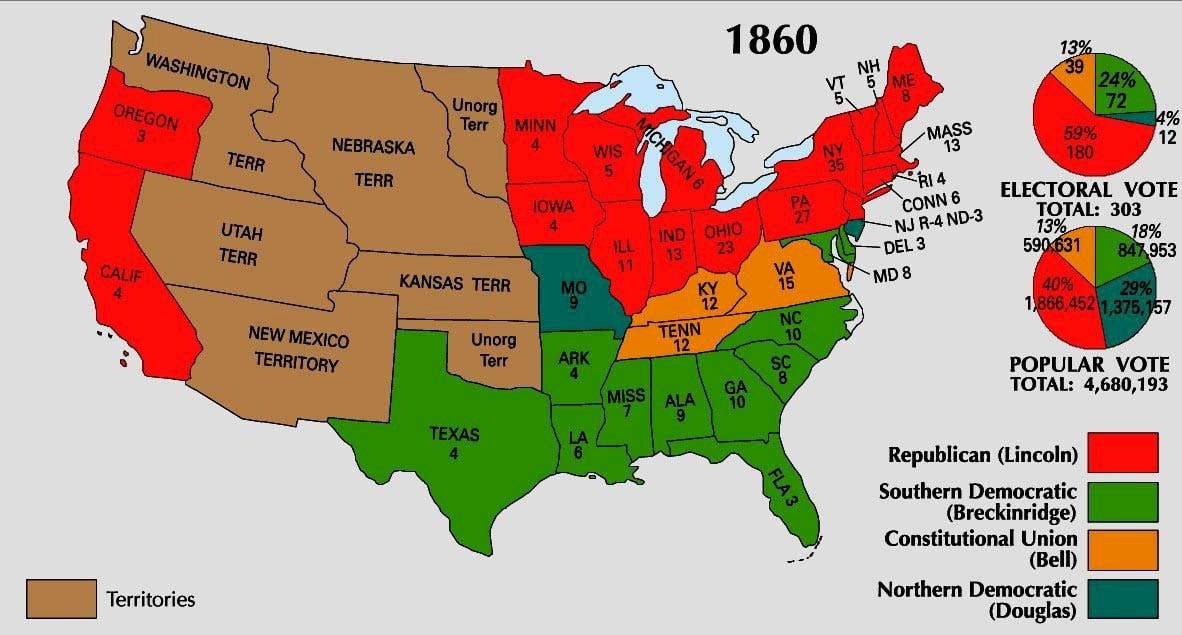

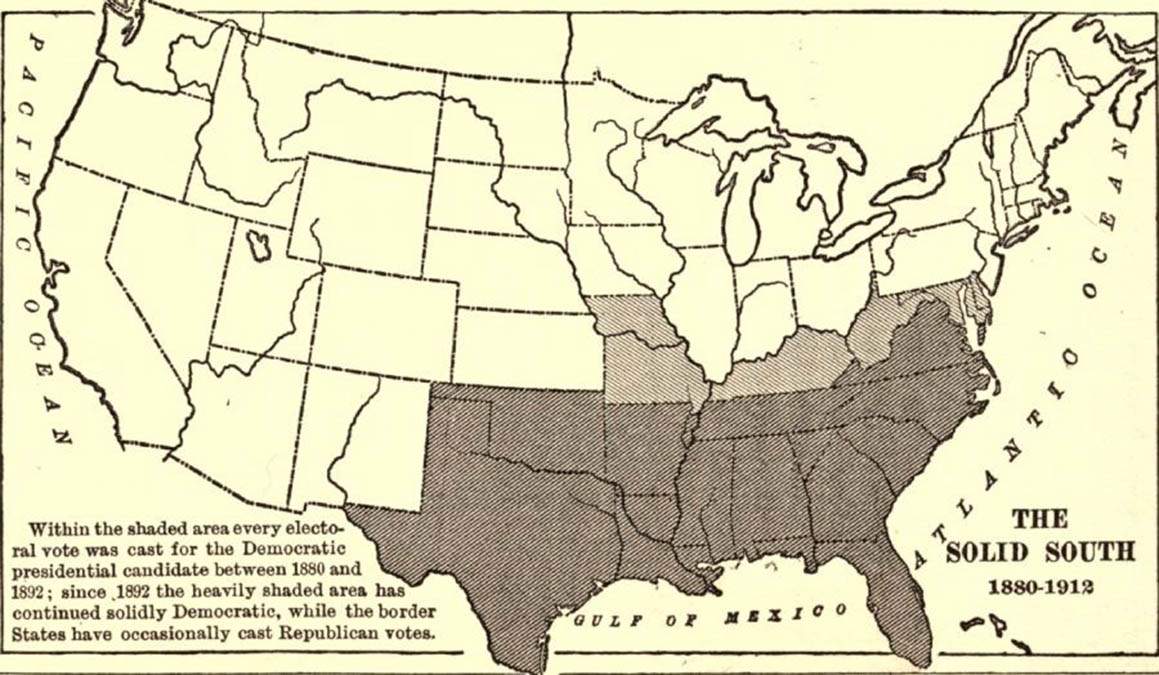

In 1860, Illinois politician Abraham Lincoln won the Republican Party presidential nomination. The party platform was firmly opposed to slavery. Southern states voted strictly Democratic, and the nine states of the “Deep South” did not even allow Lincoln’s name on the ballot! Nevertheless, Lincoln won both the popular and Electoral College vote due to the overwhelming population advantage of the North. Seeing that it could no longer influence presidential elections, the South chose to secede from the Union.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

On December 20, 1860, the first Southern state seceded even before Lincoln’s inauguration as president. Within months, other Southern states had joined South Carolina and formed a new nation: the Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederacy. Often referred to simply as “the South,” the CSA affirmed that it was separating from the United States on April 12, 1861, when South Carolina forces fired on US Navy ships coming to resupply the garrison at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. Thus, the Battle of Fort Sumter began the brutal American Civil War (1861-65).

Politics During the American Civil War (1861-62)

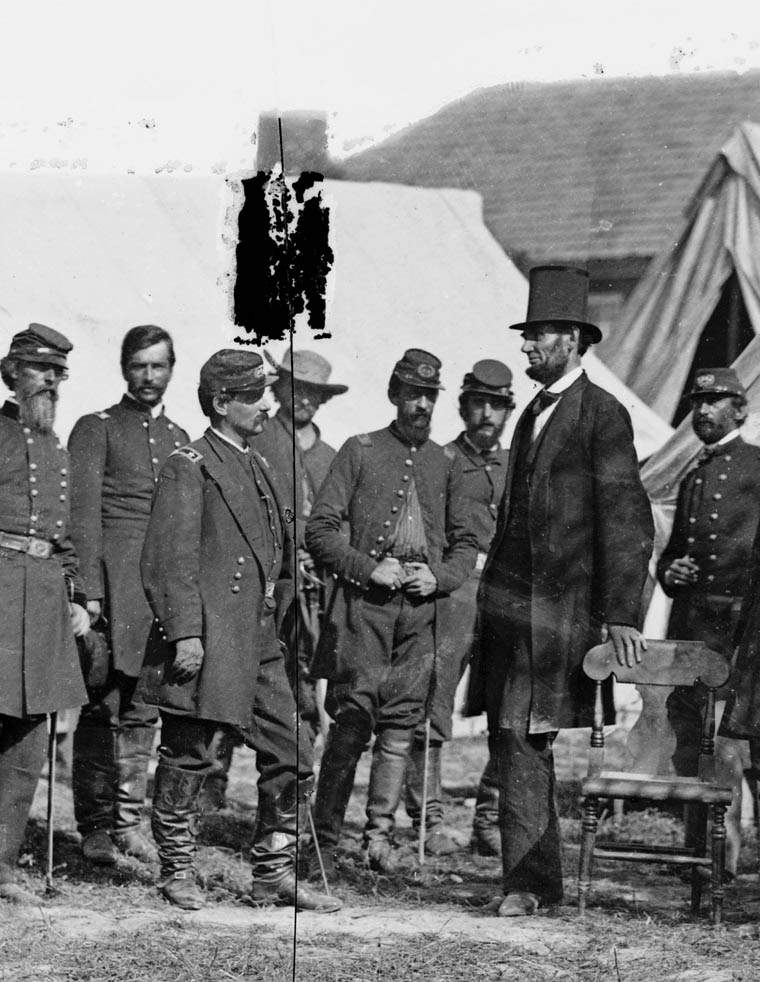

Abraham Lincoln and his administration found themselves in a difficult position: ending the rebellion of the South (hence, the popular term rebels for Confederate forces) while not utterly destroying the South. Lincoln wished to reunite the nation, not destroy a foe. This presented some difficulties: How hard should the Union fight to defeat the Confederacy? Although the North had a much larger population and the vast majority of the nation’s industry and railroad lines, the South was able to fight a less-taxing defensive war and could wear down the North’s political will through high casualties.

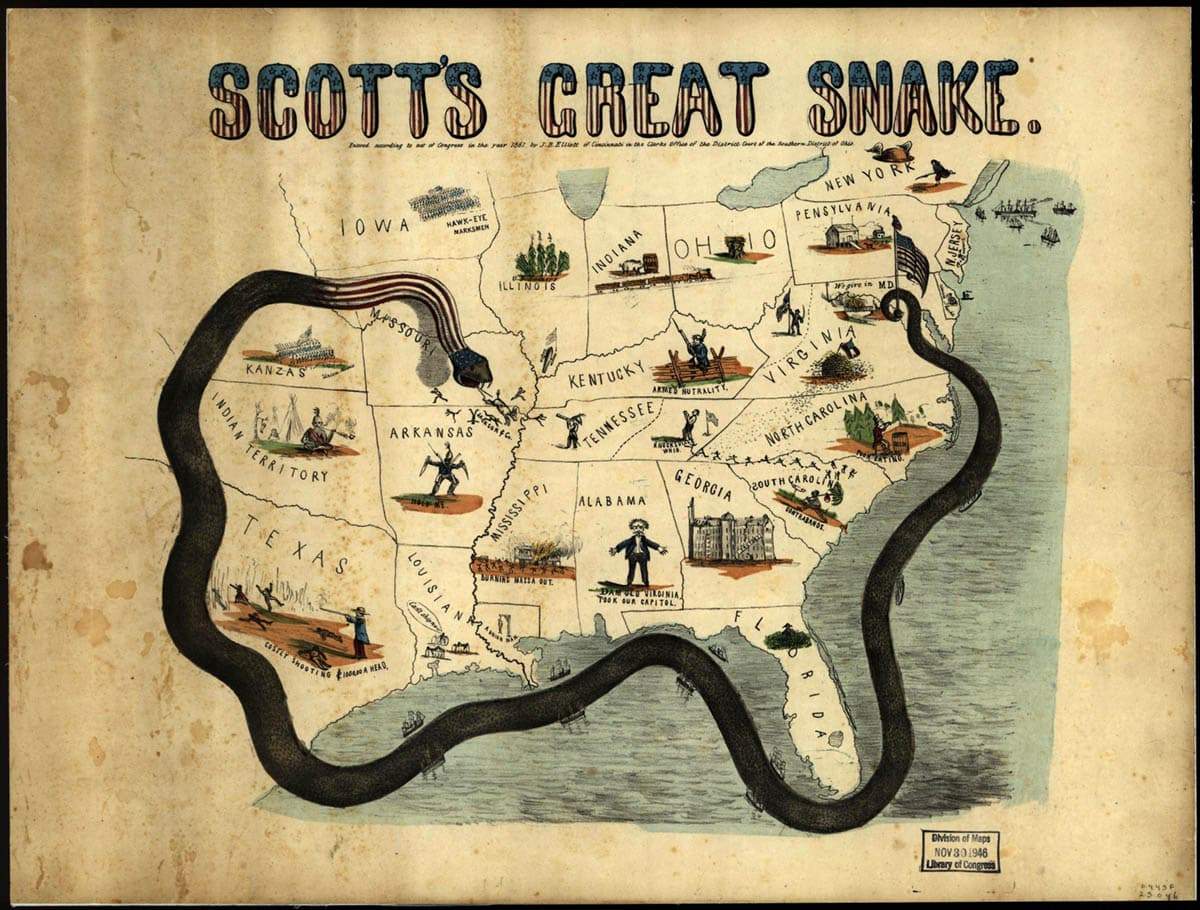

To avoid high casualties and decimating the South’s infrastructure through physical fighting, the North used a naval blockade, often dubbed the “Anaconda Plan,” to slowly strangle the South economically and diplomatically. The plan was that the CSA would surrender once it could no longer sell cash crops to Europe or hope to gain diplomatic recognition from France or Britain. During this period, the Union chipped away at the Confederacy’s frontier and seized coastal cities like New Orleans. Lincoln did not free the enslaved people during the first year of the war in order to keep slave-owning border states like Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri in the Union.

Politics During the American Civil War (1862-65)

The war entered a new phase in September 1862 with the Battle of Antietam. In this battle, the South invaded the North in order to scare the North into an armistice. Confederate General Robert E. Lee marched into Maryland in hopes of sowing panic close to the Union capital of Washington, DC. However, Union general George McClellan won the engagement, and president Abraham Lincoln made a fateful speech at the battle site on September 22. In his famous Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln declared that all slaves in states still in rebellion against the Union on January 1, 1863, would be legally free.

Although Lincoln’s speech did not sway the South, the Emancipation Proclamation had important political ramifications for the rest of the war. First, it added a moral and ethical component to the war besides simply holding the Union together. Second, it established the political precedent that slavery was unacceptable in the United States. Third, it reminded European powers like France and Britain that the Confederacy strongly supported slavery, reducing the likelihood that those two anti-slavery nations would recognize the Confederate States of America as a separate nation. Finally, it marked the turn to a more aggressive Union military strategy against the Confederacy.

Politics at the End of the American Civil War (1864-66)

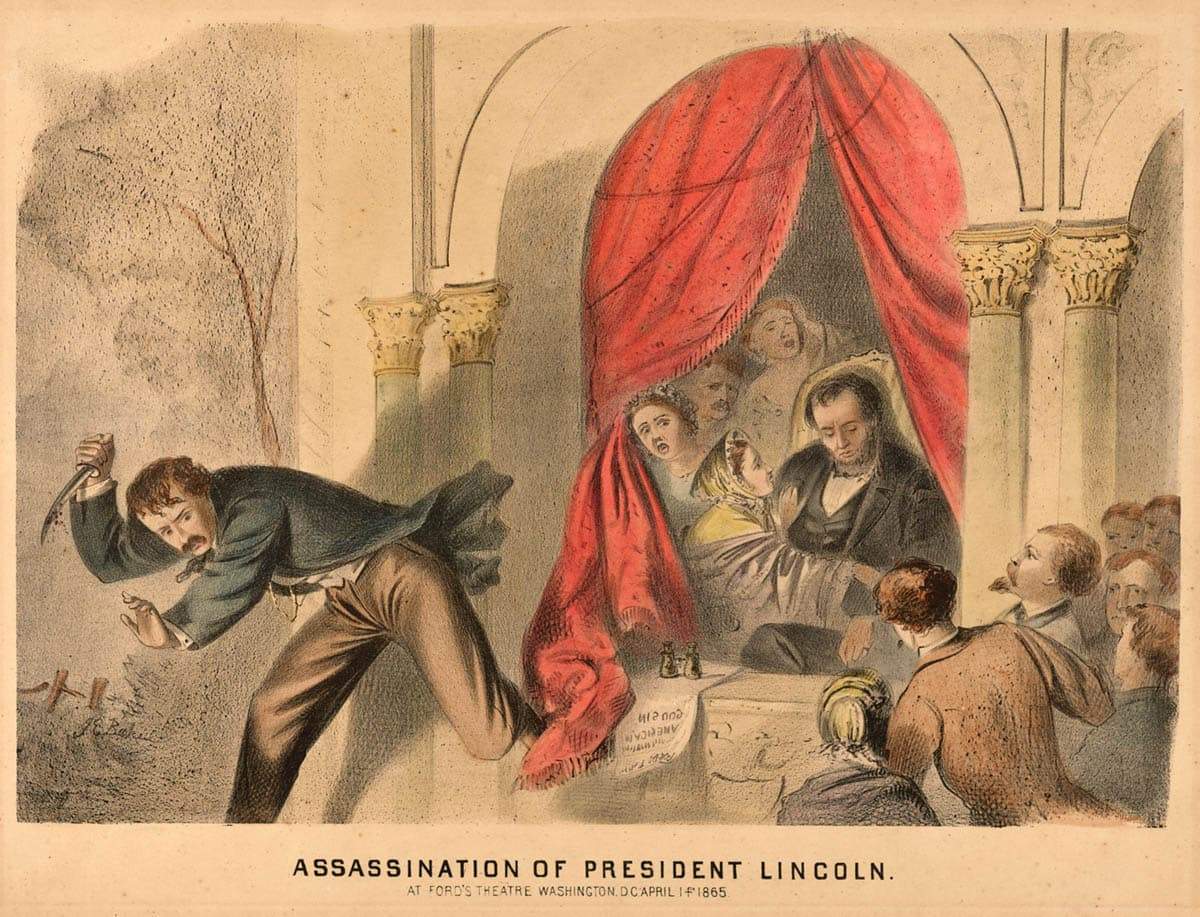

By 1864, the Union was on an inevitable path to decisively win the Civil War. After Antietam, the South attempted to invade the North again in 1863, resulting in the Battle of Gettysburg. This battle was the largest of the war and is often considered the “high tide of the Confederacy.” Defeated, the Confederates retreated south from Pennsylvania and spent the rest of the war on the defensive. Abraham Lincoln won re-election in the autumn of 1864 and looked forward to the end of the War. Unfortunately, he was assassinated by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth on April 15, 1865, while watching a play at Ford’s Theater in Washington DC, only weeks before the final surrender of the Confederacy.

The assassination of Lincoln and the inauguration of his southern vice president, Andrew Johnson, revealed the deep-rooted challenges of reforming the South. Although the North had easily won militarily, freeing the enslaved people by force of arms, many southerners showed little desire to repudiate racial segregation, agrarian lifestyles, and strong support for state rights over federal unity. Thus began an era of intense political struggle over how to treat the former Confederate states: should their rights quickly be restored, or should the Union govern them to ensure fair treatment of formerly enslaved people? In 1865 and 1866, President Johnson dealt leniently with the South, and those states quickly passed Black Codes to restrict the freedoms of former slaves.

Radical Republicans & Reconstruction (1867-76)

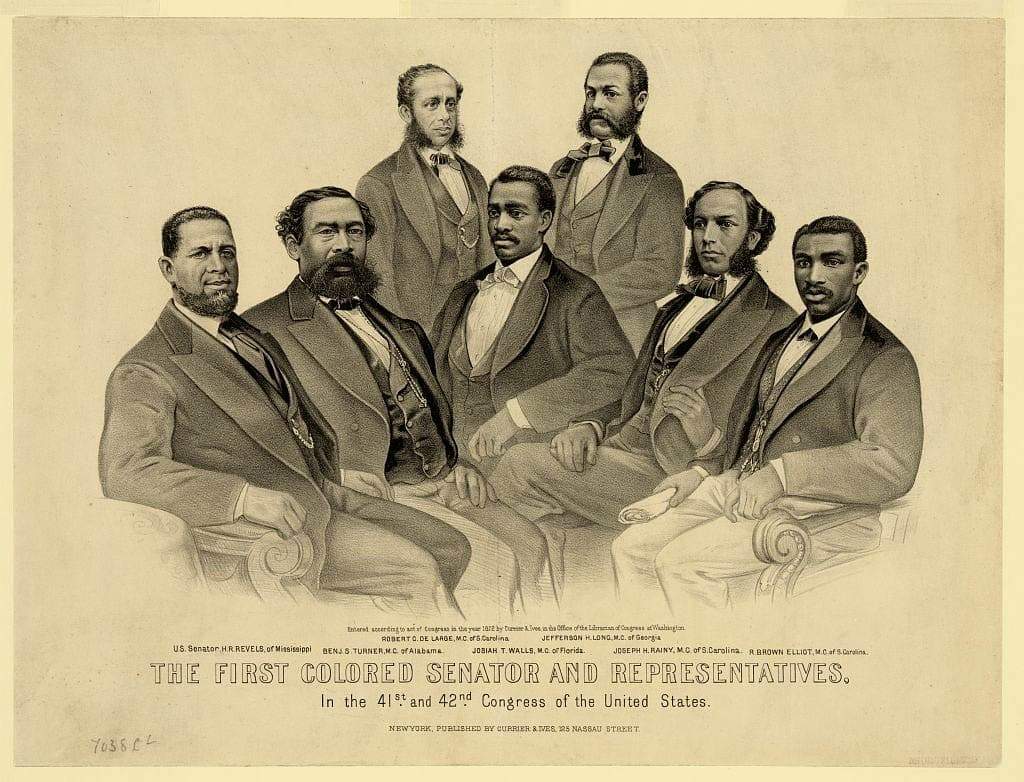

In 1867, Radical Republicans took control of Congress and held such an advantage that they could override any vetoes of Reconstruction legislation by president Andrew Johnson. Essentially, Congress took control over Reconstruction, which was the period of political reform during which the South was “reformed” in order to re-join the United States. During the late 1860s, the Freedmen’s Bureau worked to ensure that freed slaves were treated fairly in the South, representing a significant increase in federal control over the states.

With the South not represented in Congress during early Reconstruction, the three Reconstruction Amendments to the US Constitution were passed: the 13th Amendment (1865) abolished slavery, the 14th Amendment (1868) granted citizenship, and equal rights to all citizens, and the 15th Amendment (1870) granted the right to vote to Black men. Unfortunately, these Amendments did not change the attitudes of many southerners. By the early 1870s, many in the North were becoming weary of maintaining Reconstruction and keeping the South under federal military occupation.

End of Reconstruction (1876-1877)

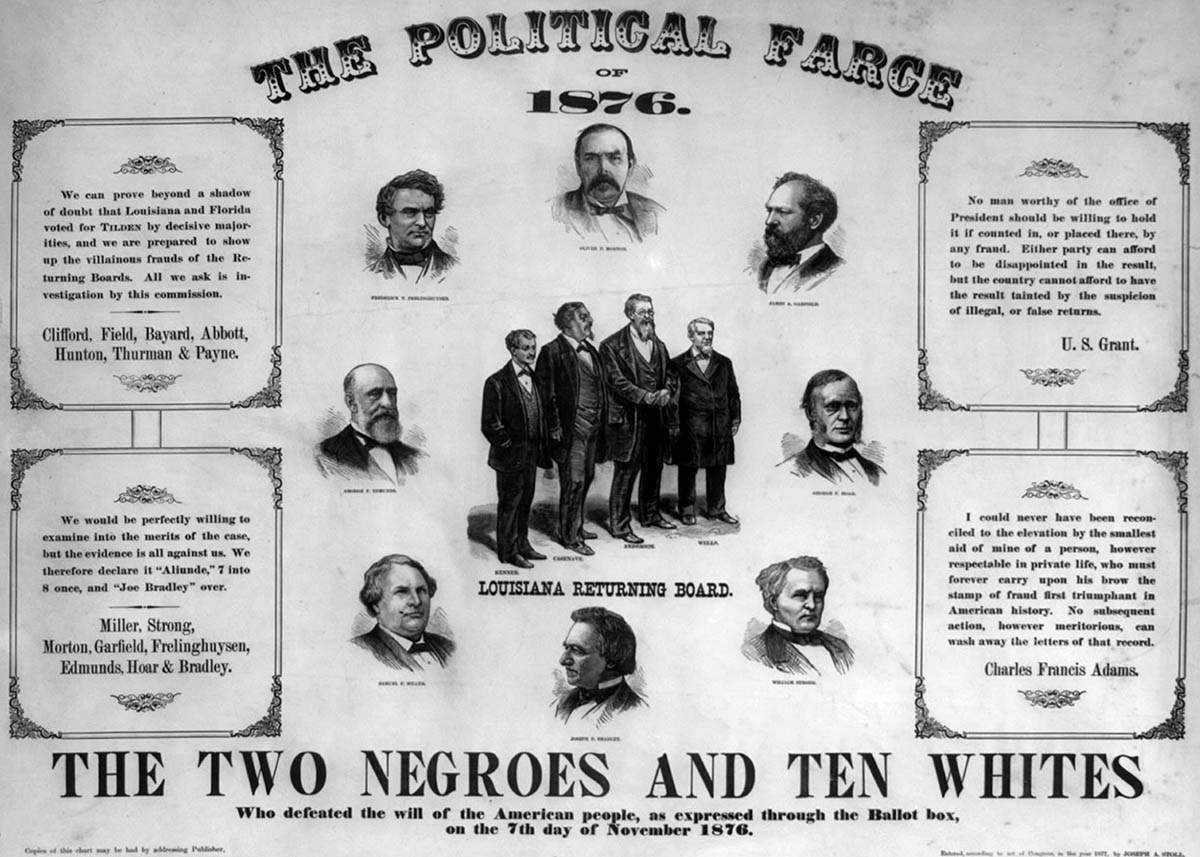

The political difficulties of Reconstruction came to a head in 1876. Despite the federal government’s attempts to reform the South, racist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan terrorized Black citizens. Local and state governments worked to prevent racial minorities from exercising any political power by suppressing the right to vote. As a result of voter suppression in the South, the Republican Party was no longer guaranteed political victory now that the southern states had all been re-admitted to the Union. Republican presidential candidate Rutherford B. Hayes lost the popular vote to Democrat Samuel Tilden, but neither man received a majority in the Electoral College, allegedly due to corruption and voting irregularities from both racist voter suppression and federal troops suppressing southerners’ votes.

With no candidate winning in the Electoral College, a commission of congressmen and Supreme Court justices was convened. Eventually, Hayes was awarded the disputed electoral votes, allegedly in exchange for a deal with Democrats: he would remove federal troops from the South. In 1877, upon taking office, Hayes removed troops from the South, officially ending Reconstruction. Unfortunately, the absence of troops in the South allowed southern states to engage in voter suppression and segregation for the next eight decades.

Political Party Evolution: Republican Party

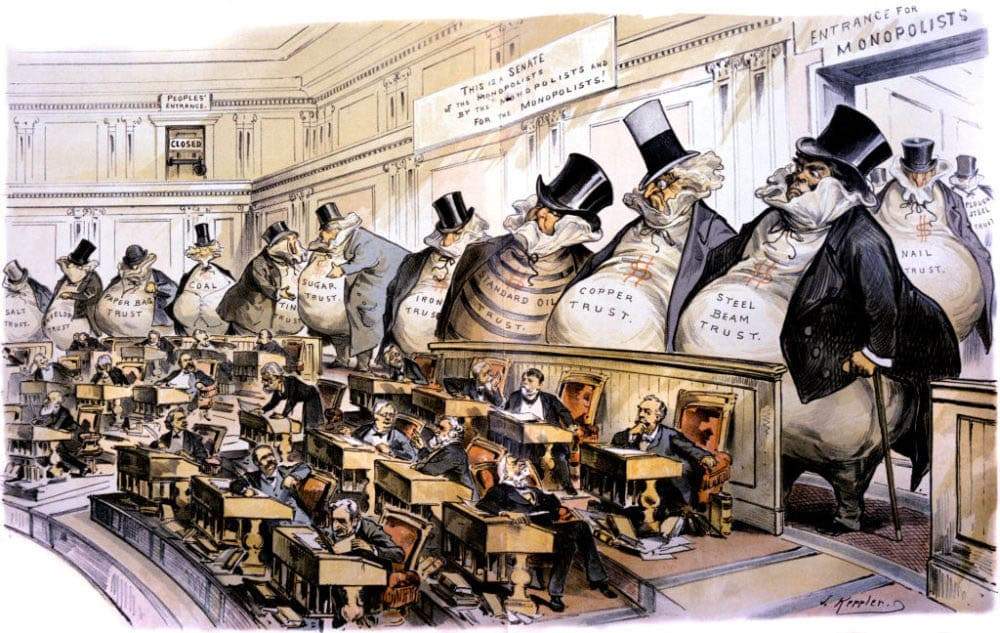

Immediately prior to the Civil War and during the early years of Reconstruction, the Republican Party was committed to the abolition of slavery and civil rights for African Americans. During and after the War, the Republican Party became fondly known as “the Party of Lincoln” and received much praise for abolishing slavery and preserving the Union. However, political weariness over Reconstruction led to the Republican Party replacing civil rights with economic growth and pro-business policies as its primary platform.

As the political party of the North, and with president Lincoln having used federal government power to temporarily nationalize the railroads and telegraph lines during the Civil War, the Republican Party was in the position to be the party of industry and building infrastructure. Indeed, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 under Republican president Ulysses S. Grant helped solidify the Republican Party as the party of industrial growth during the Gilded Age (1865-1890).

Political Evolution: Democratic Party

While the Republican Party enjoyed national dominance after the Civil War, the Democratic Party was severely wounded. When the Radical Republicans in Congress overruled president Andrew Johnson and imposed harsher terms during Reconstruction, many Democrats were ineligible for political office due to their wartime support for the Confederacy. In repudiation of the North, voters in the South became extremely loyal to the Democratic Party. So many voters were so devoted to the Democratic Party, which was pro-segregation at the time, that the term “yellow dog Democrat” was coined: voters would rather vote for a yellow dog than any Republican.

Democrats controlled the South, especially the rural areas, until the 1960s. Beginning in the 1940s, however, cracks appeared in the Democratic Party, which had been dominant nationwide since the Great Depression. While most of the nation supported the liberal fiscal policies of Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt, many Southern Democrats began feeling that FDR and urban Northern Democrats were far too liberal on social policies and civil rights. In 1948, the Dixiecrat Party emerged briefly in opposition to the pro-civil rights policies of national Democrats, pledging its own support for continued racial segregation in the South.

Long-Term Political Effects: Stronger Federal Government

The Civil War saw a significant increase in central government power. Although this tends to occur during every war, the fact that this war occurred on American soil and was arguably the world’s first industrialized war made swift federal action extra important. Abraham Lincoln was a very active commander-in-chief and used his powers to nationalize railroads and telegraph lines, institute a draft, and suspend habeas corpus (the right to a trial) in border states.

Government action also censored the news, subsidized railroads, and provided land grants to help settle the western frontier (and prevent Confederate expansion). Although the nationalization of industries was temporary, the precedents set by suspending habeas corpus, censoring the news, subsidizing industries, and providing land grants would be used in later decades. The Civil War had a lasting political effect of proving that the central government in Washington DC would not hesitate to use physical force to enforce the law and uphold public order.

Long-Term Political Effects of the American Civil War: Slow March for Civil Rights

While the Civil War did see rapid political advancements in terms of central government power, the South saw little political change at the state and local level after Reconstruction. Unfortunately, the Compromise of 1877 saw civil rights erode in the South until the renewal of civil rights action at the federal level after World War II. While slavery could not be restored due to the 13th and 14th Amendments, southern states actively enforced racial segregation of public facilities, allowed private businesses to engage in segregation, and used discriminatory laws to suppress racial minorities’ ability to register to vote.

Although some cities in the South attempted to “northernize” by developing industry and commerce, embracing the New South philosophy, most of the region remained primarily rural and agricultural. Unable to vote in meaningful numbers and denied public sector jobs of any importance, Black citizens had virtually no political power. This system remained stagnant until the 1950s when Supreme Court decisions began setting up new conflicts between a pro-integration federal government and pro-segregation Southern states.