The most consequential political organization in American history didn’t get its start in a party headquarters or a smoke-filled room. It began when a few working-class kids designed a costume, which grew into a movement and ultimately an army. And it ended with a civil war. In between, the story of the Wide Awakes of 1860 helps explain how politics can evolve, step by step, into violence.

Edgar S. Yergason is not who you imagine when you consider who started the Civil War. Not a president, or a general, or an enslaver, Eddie Yergason was a gawky 19-year-old textile clerk. But using his skills as a designer—and as a thief—he became the accidental founder of what the New York Tribune would call “the most imposing, influential and potent political organization” in American history.

Yergason was living in Hartford, Connecticut, on February 25, 1860, at the start of the state’s spring gubernatorial race. It all seemed fairly ordinary: Local Republicans were running a well-known incumbent candidate, had a famous speaker in town to give a campaign speech, and were planning a torchlit parade afterward. But 1860 was no ordinary year. National tensions over slavery were already boiling over when, a few months earlier, John Brown launched a raid on Harpers Ferry, hoping to spark a slave uprising. It ended with his body swinging from a Virginia gallows—pushing Americans further into their political corners. Many expected an ugly year culminating in a chaotic and potentially violent presidential election in November.

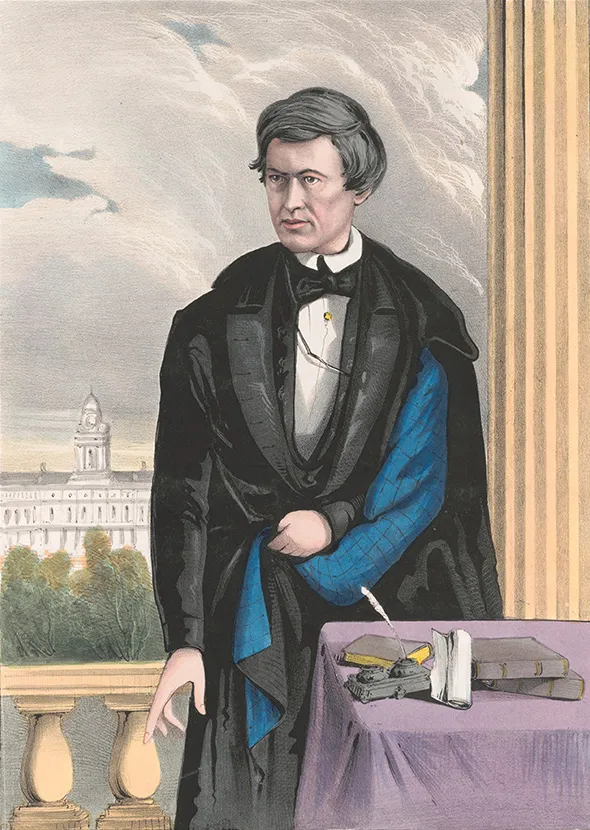

The speaker that February night was Cassius Marcellus Clay, a bold and brawling Kentucky abolitionist, equally skilled with a stump speech and a bowie knife. Clay had famously fought off six brothers who had attacked him with guns, daggers and cudgels at a political debate, killing one with a knife. In Connecticut in 1860, he was promising to launch “an insurrection” against slavery.

Yergason wanted in. He especially wanted to participate in the parade after Clay’s speech. But he knew that in the haphazard marches common at the time, torches went fast, grabbed up and rarely returned. So he spent much of the afternoon perched in front of Talcott & Post’s textile shop. He was supposed to be working. Mostly he was watching as crowds gathered and employees at Hank’s lighting store piled oil-filled metal torches on a wagon parked tantalizingly close.

Then Yergason made his move. He shot forward, snatched a torch from its long pole, stuffed it under his new coat, and disappeared into Talcott & Post’s textile shop. Inside the dim, rambling building—past rows piled with Persian rugs, hoop skirt frames and rolls of French velour—Yergason found his fellow clerks. Opening his coat, he displayed his prize, the stolen torch, but also a slick of oil staining his new garment. The clerks chuckled at Yergason’s luck. Grumbling, he marched to the rolls of fabrics and cut himself a yard and a half of waterproofed black cambric. Working carefully, he threaded a cord onto a long steel needle and began to sew.

Decades later, Yergason would brag that the garment he invented was “something very novel for a political campaign.” His friend Harold P. Hitchcock agreed, but added that Eddie’s democracy-disrupting design got its start “quite accidentally,” all because “some of us young fellows with fastidious ideas” wanted to keep torch oil off their clothing.

Yergason’s fastidious fellows got to work, too. Soon each was stitching his own garment, stealing his own torch and jamming it onto a six-foot curtain rod. As Clay wrapped up his talk across the street, five Talcott clerks threw flashing black capes over skinny shoulders and stepped out into the February darkness.

Clay had delivered, framing Connecticut’s gubernatorial race as a kickoff to an antislavery crusade, to culminate with Republicans winning the presidency in November. He focused on how slavery imposed on everyone—even the primarily white voters up in Connecticut, who might think they were distant bystanders.

A propulsive account of our history’s most surprising, most consequential political club: the Wide Awake antislavery youth movement that marched America from the 1860 election to civil war.

Few of these voters were outright abolitionists, but they resented that the interests of enslavers took precedence over those of the Northern majority. Indeed, white Southerners made up barely one-quarter of the American population, and enslavers numbered fewer than 400,000 in a nation of 31 million people. Their capture of the political system undermined the very fundamentals of democracy. For example, the Three-Fifths Compromise inflated the political influence of enslavers by counting 60 percent of enslaved populations in their congressional apportionments (while denying all enslaved people the right to vote, of course). By 1860, this had allotted 30 extra congressmen to Southern states, which gave them extra votes to add additional slave states—whether by force, as in the Mexican-American War, or by breaking longstanding agreements to keep the Kansas and Nebraska territories free. Even the supposedly independent Supreme Court fell under this nefarious sway. When the court decided, in 1857’s Dred Scott decision, that African Americans could not be citizens of the United States, and questioned the federal government’s power to limit slavery, five of the nine justices were enslavers themselves.

Perhaps as dangerous, Clay and other antislavery Republicans argued, pro-slavery forces were abusing their power to stifle dissent. In the South, antislavery voices were driven out of communities. The offices of abolitionist newspapers and lecture halls hosting antislavery speakers were attacked by mobs, even up in Philadelphia and Boston. On the floor of the U.S. Capitol, the abolitionist senator Charles Sumner was beaten nearly to death for giving an antislavery speech.

Slavery was not a distant evil. It was a menace to democracy, a nationwide “Slave Power” conspiracy silencing the American majority using dirty tricks and open violence.

After two and a half hours of speechifying, Clay led 1,500 fired-up men and women out into the night. The crowd chattered and gossiped. A young Republican named George P. Bissell shepherded them into order, standing atop a wagon and waving a floppy white hat. Republican volunteers handed out torches. Then Bissell spied five young clerks standing at attention, with lit torches on long poles, wearing … shimmering black capes? Bissell hollered his compliments to the Talcott boys and, with his white hat, waved them to the front of the march.

Eddie Yergason made $50 a year. He slept on a cot deep in that rambling textile store. In his spare time, he sketched cartoons and wrote to his parents in rural Windham, Connecticut, about his homesickness. His fellow cape-wearers were little better off—in their early 20s, living in cramped boarding houses or with their parents, taking orders from Mr. Talcott and Mr. Post all day. Now they were uniformed men, leading Hartford’s prominent Republicans down Main Street.

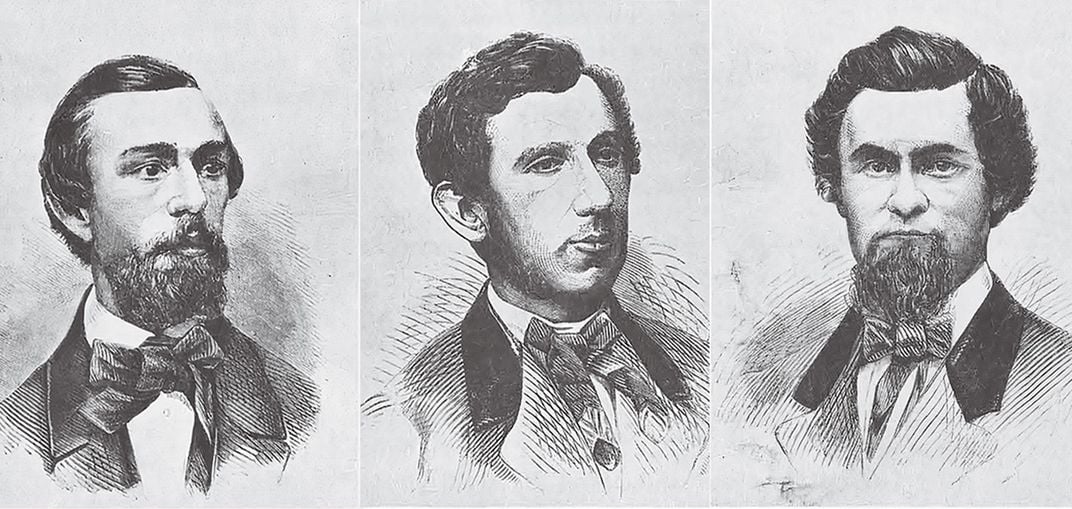

But the brutal realities of antebellum politics broke the spell. Hostile Democrats gathered in the darkness. Though many once respected the party, Republicans now called them “Shamocrats,” a pathetic imitation of their former glory, goons doing the Slave Power’s bidding. Now they attacked the marchers, rushing into the crowd and grabbing at torches. One young Republican was knocked down and came up with a gash on his forehead. Others dove into the fray, pushing back Democratic brawlers and recapturing their torches. A short but solid Republican, with flaring eyebrows and a jutting goatee, became an instant legend for fighting back ferociously.

It was a minor fracas by the standards of 19th-century political warfare, but it looked like proof of everything Clay had warned against. Slavery was not just a matter of plantations in Georgia or Texas. The Slave Power and the Democratic Party imposed on everyone. The fight for democracy would play out in the streets of Hartford.

The march ended at Clay’s hotel. He went to bed. Workers collected torches. Yergason carefully folded his makeshift cape, a bit of drapery on its way to becoming an artifact of a movement that would remake American democracy. Another young man, an editor for the Hartford Courant, put together his article on the evening. In 1860, he cheered, Republicans were finally “Wide Awake.”

Hartford was a funny place to launch “an insurrection.” It was perhaps the most prosperous city in America, the prim capital of the nation’s richest state per capita. The whole town exuded a settled, Yankee order, anchored around a tidy Main Street planted with elm trees and church spires. But Hartford was also the center of a titanic manufacturing boom, especially famous for its gun factories. Eighty percent of the nation’s firearms were manufactured in the region. The clatter of gunfire from Colt and Sharps factories periodically shattered the New England calm—a hint at what was coming.

Hartford’s settled atmosphere was broken by the boys buzzing around downtown. Although an old elite controlled the state, much of the daily work was done by the young clerks who kept the city’s gun factories and insurance brokers and publishing houses in business. Yet many of those lads and ladies agreed with the newspaperman Joseph Hawley, who complained about the “awful, awful, awful fogyism of Connecticut.” The small state was dominated by a few old Puritan families, conservative in business and in politics, making it difficult for a young generation to rise. Those buzzing clerks were primed to go off.

Connecticut also sat on the northern edge of the so-called doubtful states, where the future of slavery would be decided. To the north, across New England and the Upper Midwest, antislavery Republicans held sway. But in a band running from Pennsylvania to Connecticut, and from New Jersey to Illinois, voters were still making up their minds. This largest bloc of the electorate could go Republican or Democratic, deciding everything. Many of those primed clerks had heard about the Clay march and Yergason’s cape. They talked about it over quick lunches at Cooley’s Coffee Room or chowder suppers in Mrs. McClaffin’s boarding house. A quarter century later, one of them recalled their shared sense that “there was real danger ahead.” And so they decided—in typical Yankee fashion—to hold a meeting about it.

One week after the Clay march, 36 young men squeezed into the shabby third-floor apartment of J. Allen Francis, above the City Bank where he worked. Usually, the boys gathered in Francis’ rooms to talk politics and sing, accompanied by his jaunty melodeon. But on March 3, 1860, they came to launch a movement. Most were between 18 and 24 years old at a time when the voting age was 21; few had yet voted in a presidential election. Certainly, none had done anything like this.

But they got to work, voting to organize a club, adopt a spiffed-up version of Yergason’s shiny black cape as a uniform and elect a captain. Most agreed it should be James Chalker—the combative, goateed Republican who fought Democrats so fearlessly a week earlier.

Now the boys had to pick a name. A political club’s title could signal its background and intensions. There were elite organizations with names like the “Young Men’s Republican Club” and violent street gangs like “the Dead Rabbits” or “the Blood Tubs.” The Hartford boys chose a middle path. Citing the article in the Courant, 22-year-old Henry P. Hitchcock—always creative and always loud—shouted: “Why not name it ‘Republican Wide Awakes’?” The phrase “Wide Awake” was a popular expression at the time, used for anyone who was standing up for themselves. It fit with Republican rhetoric about an aggrieved majority finally pushing back.

But it contained another message, a dog whistle that later generations might overlook. During the 1850s, the anti-immigrant Know Nothing movement had often called their crews “Wide Awakes.” They even favored floppy white hats, also called “wide awakes,” as a kind of gang sign. These nativists persecuted Irish Catholic immigrants especially, convinced that they were part of a conspiracy by the pope to control American democracy. It was utter nonsense, but many young Protestants believed it. Some of the boys in Francis’ apartment had troubling associations with that bigoted old movement. George Bissell had even waved the boys in capes to the front of the parade with a floppy white hat. Now, with the Know Nothing movement puttering out, some of these boys were finding a new political use for the term “wide awake.”

What did anti-immigrant conspiracy theories have to do with antislavery Republicans? First, both narratives targeted a common villain: the Democratic Party, accused of welcoming the pope’s Irish Catholic foot soldiers, on the one hand, and enforcing the Slave Power’s anti-democratic rule on the other. On top of this, both narratives blamed small, discrete groups (Catholics and Southern enslavers) for conspiring to steal the political birthright from the North’s growing, Protestant, native-born majority. The key difference was that only one of those fears was based in fact.

There is no defense for this bigotry, and Republican leaders such as William Seward were working to clear such xenophobia from their ranks. But the youths who formed the Wide Awakes linked it all in their minds, building a new movement to fight what they saw as multiple conspiracies against democracy. That the organization that would help destroy slavery grew from such ugly roots is a useful reminder that these young Wide Awakes were neither heroes nor villains but a fascinating and troubling mix. They were not simply fighting an earlier battle in what may feel to us like a perpetual culture war that continues to this day. The coalitions that make up politics scramble radically over time, and the political conflicts of that era are not ours.

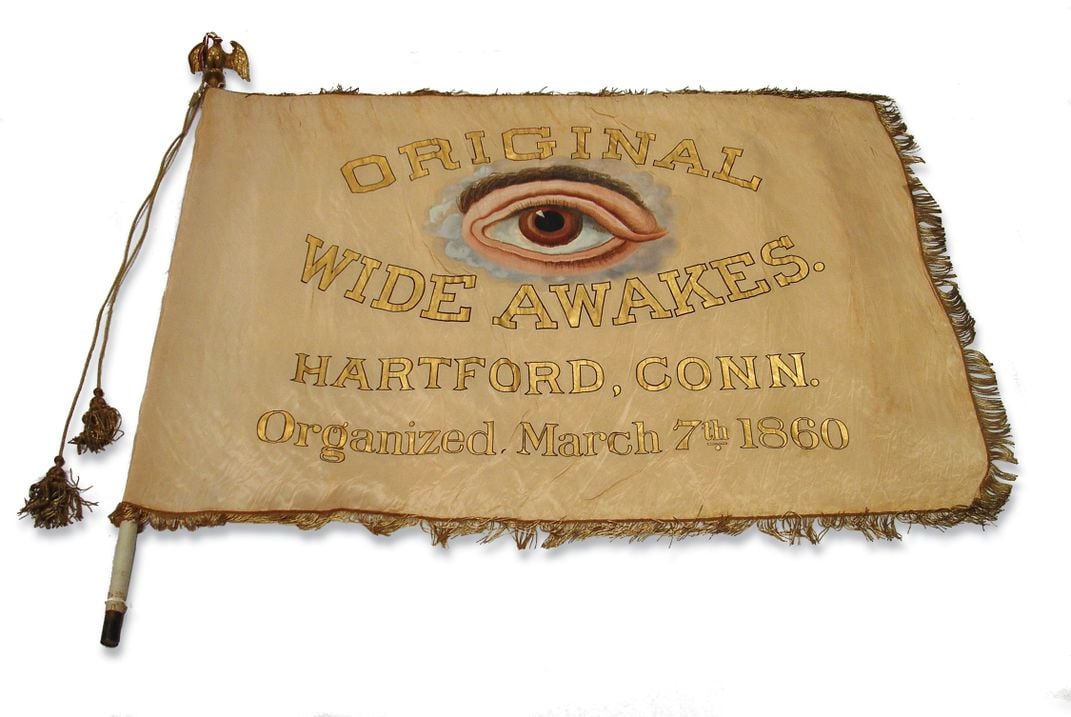

The 36 original Wide Awakes left Francis’ apartment with a uniform, a leader and a name. Yergason wrote his mother the next day. They had 50 members, he boasted, already up from 36, each with “a Black Oil Cloth Cape to go over the Shoulders A Black Cap & torch, all alike, there will be 2 or 3 hundred in it I presume.” Not long afterward, he wrote home again, announcing that there were “over 500 in our Company.” Then something even more impressive happened. Yergason’s club met Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln was not a household name in early 1860. That spring, the lanky Illinoisan was on a Northeastern speaking tour in the run-up to the Republican nomination contest. Hartford was his sixth stop in little over a week. Yet Lincoln gave a tremendous speech, packing its City Hall and warning that slavery was “a venomous snake” poisoning the nation. Afterward, he stepped out into the bracing Connecticut night for a procession back to his hotel. With so many events in one week, he had met his share of local dignitaries and bumpy rides.

But in Hartford, something unusual stepped out of the darkness—stern young men wearing black soldier’s caps and black capes. Each clutched a lit torch on a long staff. Each was silent. This corps encircled Lincoln’s carriage and began the march. They were sober, dignified, even soldierly. Torchlight flickered on Lincoln’s bemused face as he assessed the uniformed boys around him. He could not have imagined how this strange new force would become entangled with his destiny, nor that almost exactly one year later, hundreds of members of the same movement would follow him down Pennsylvania Avenue to his inauguration.

That was all in the future. In March 1860, Hartford’s boys had work to do. They began growing their club, first among the clerks working downtown, then with the pistol-makers at Colt’s factory. Soon, Chalker, as captain, took their show on the road. One hundred black-caped Wide Awakes rode a special train to a Republican rally in Waterbury, Connecticut. In the town square, “a howling mob” of Democrats disrupted the speakers, shouting, throwing rocks and even rolling a flaming barrel of tar down the street.

As they hollered, Chalker lifted his head. “About face!” he commanded. One hundred uniformed Hartford boys spun around, facing the mob. Then he shouted, “Wide Awakes, do your duty. … Charge!”

With that, columns of Wide Awakes launched into the motley hecklers, swinging their torch staffs and clearing the square of some 200 troublemakers. Waterbury’s Republicans got the message. At the next meeting, they converted their respectable Republican Club into a Wide Awake fighting force.

Hartford’s invention spread. Yergason updated his mom that clubs “have sprung up all over the State patterned after us, are in New Haven and in Waterbury and in New Britain and in Bristol & all around & every time we Come out We make New Republicans of the Democrats.” He even recruited his brother Henry, formerly a Democrat.

As the clubs grew, they evolved. The Waterbury fight hinted at this new direction. Wide Awake clubs started practicing military drills, borrowed from Lieutenant Colonel William J. Hardee’s Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics. They were showing publicly that Republicans would no longer be imposed upon. Not by local Democrats. Not by old fogies. Not by enslavers in the South.

When Yergason designed his cape, it was meant to keep torch oil off his new coat. But the meaning of those capes became something more assertive. It was the militaristic air of the uniformed, trained and officered boys who wore them that really appealed to wide-awake young people across Connecticut. Their companies marched in silence, punctuated by coordinated cheers. They forbade drunkenness or cigar-smoking in their ranks. In an age of raucous, boozy public politics, they were not, in all honesty, much fun. But recruits were looking for something beyond a political party.

The Wide Awakes gave off what one Southern observer called an “air of bayonet determination.” This was part of the movement’s appeal. In addition to the creeping power of slavery, many Americans worried about street-level chaos. Wild public assaults, called “mobbings,” gripped the nation, with at least 1,218 recorded between 1828 and 1861. Targets ranged from abolitionists to immigrants to labor organizers. Election days often devolved into riots. Vigilantes fought in gold rush California, in “Bleeding Kansas,” in abolitionist Boston, even in the nation’s capital. And often, it seemed that pro-slavery Democrats led the mobs, and antislavery Republicans or abolitionists bore the brunt.

In fact, Southerners had long mocked Northerners as cowards. “You may slap a Yankee in the face, and he’ll go off and sue you, but he won’t fight,” one South Carolina politician joked. Now an apparent army was rising in mild old Connecticut, asserting order and stomping through Democratic neighborhoods like a partisan infantry. They did not look like cowards. Yet neither did they resemble wild-eyed abolitionist “fanatics” like John Brown. The Wide Awakes offered an appealing alternative—a moderate, organized and proud majority finally waking up.

Young ladies, perhaps surprisingly, were among the biggest fans of this militaristic movement. Many women held strong partisan beliefs but were often put off by the violent, drunken messiness of antebellum politics. The Wide Awakes, by contrast, organized public spectacles that could be sober and orderly and still thrilling. Connecticut women, like the 25-year-old schoolteacher Kezia Peck, traveled great distances to attend Wide Awake rallies, hollering slogans and waving handkerchiefs.

Thousands of new recruits had joined the movement by early April, when Republican governor William Buckingham won re-election. Yet it was news of these Wide Awakes, not the governor’s race, that really traveled, a flashing black flag catching the attention of newspapers from San Francisco to London.

The Hartford boys added one last symbol to their repertoire, which began to appear on membership forms, banners and broadsides: an enigmatic open eye, a fitting emblem for the awakening that was taking place.

If Yergason began the club with sewing skills, and Chalker trained it into a fighting force, Henry T. Sperry transformed it into a national franchise. Sperry was tall and grave, a 24-year-old railroad employee and a budding writer. His literary skills won him the office of corresponding secretary for the Hartford Wide Awakes. In spring 1860, the kid who took tickets at Hartford’s train station began to receive a flood of letters from Republicans across the North, asking how to start their own Wide Awake companies.

Sperry sent out hundreds of replies, doing more to orchestrate the Republicans’ campaign than almost any other man. Finally, he printed up a form letter explaining how to organize a club, elect a leadership, design a uniform and march at night. Trying to capture the movement’s combative verve, the young writer bragged: “Wherever the fight is hottest, there is their post of duty, and there the Wide Awakes are found.”

The fight was hot across the North. The club was spreading like a viral contagion. It was easier to transmit the Wide Awakes’ visual style than it was to articulate just what should be done about slavery, or who in the territories should decide whether a new state was slave or free. The movement activated all the knotty issues of the last decade, turning them into something people could do. Many young, working-class Republicans eagerly formed companies, but a vibrant newspaper network also spread the word. One Indiana paper asked its readers: “Cannot our young men, who admire that kind of grit, organize a ‘Wide Awake Club’ in this city?”

In Chicago, home to the Republican Convention that May, party members enlisted as many Wide Awakes in ten days as the Connecticut boys had over the entire spring. No one in town seems to have seen a Wide Awake themselves, but they modeled their clubs on Sperry’s letters and newspaper articles, demonstrating the power of the Wide Awakes’ commodified style. And the Chicago clubs made an important alteration. In a city where a whopping 52 percent of the population was born overseas, the Chicago companies insisted: “Young men of all nationalities are cordially invited to become members.” Germans, Scandinavians, Bohemians and even a handful of Irish joined up. The Hartford club’s nativist roots were falling away, hinting at the movement’s adaptability.

When 25,000 Republicans visited Chicago—a city of just 100,000—in May, the convention became a vector for Hartford’s design. Delegates tried on Wide Awake capes and marveled at torchlit processions. Lincoln’s unexpected nomination only boosted the movement, since many Americans associated Lincoln with a youthful, working-class energy symbolized by the Wide Awakes themselves. Republicans returned home to Bangor and Brooklyn, St. Paul and San Francisco, eager to form their own companies. From the biggest Eastern cities to the smallest Western settlements, recruits formed new clubs, designing uniforms, electing captains, writing aggressive constitutions. “How long must the South kick us,” asked one fired-up Wisconsin speechifier, “before we shall all be Wide Awakes?”

Back in Hartford, Chalker, a textile salesman by day, shipped at least 20,000 Wide Awake capes to new companies across the country, but soon he couldn’t keep up. Teams of women stitched makeshift capes in garment districts; newspaper ads hunted for waterproofed fabric for capes. Sperry responded to 400 letters of inquiry within a month. The club lost count of new companies around 900.

Newspaper articles and other accounts make clear that, by the end of the summer, Americans believed the country held 500,000 Wide Awakes. That number is almost certainly too large. In reality, the movement likely had between 100,000 and 250,000 members at its height, but the shared sense of a burgeoning partisan army mattered more than the actual number. Either way, adjusted for today’s population, the Wide Awakes comprised millions of members, dwarfing nearly every other mass movement in American political history.

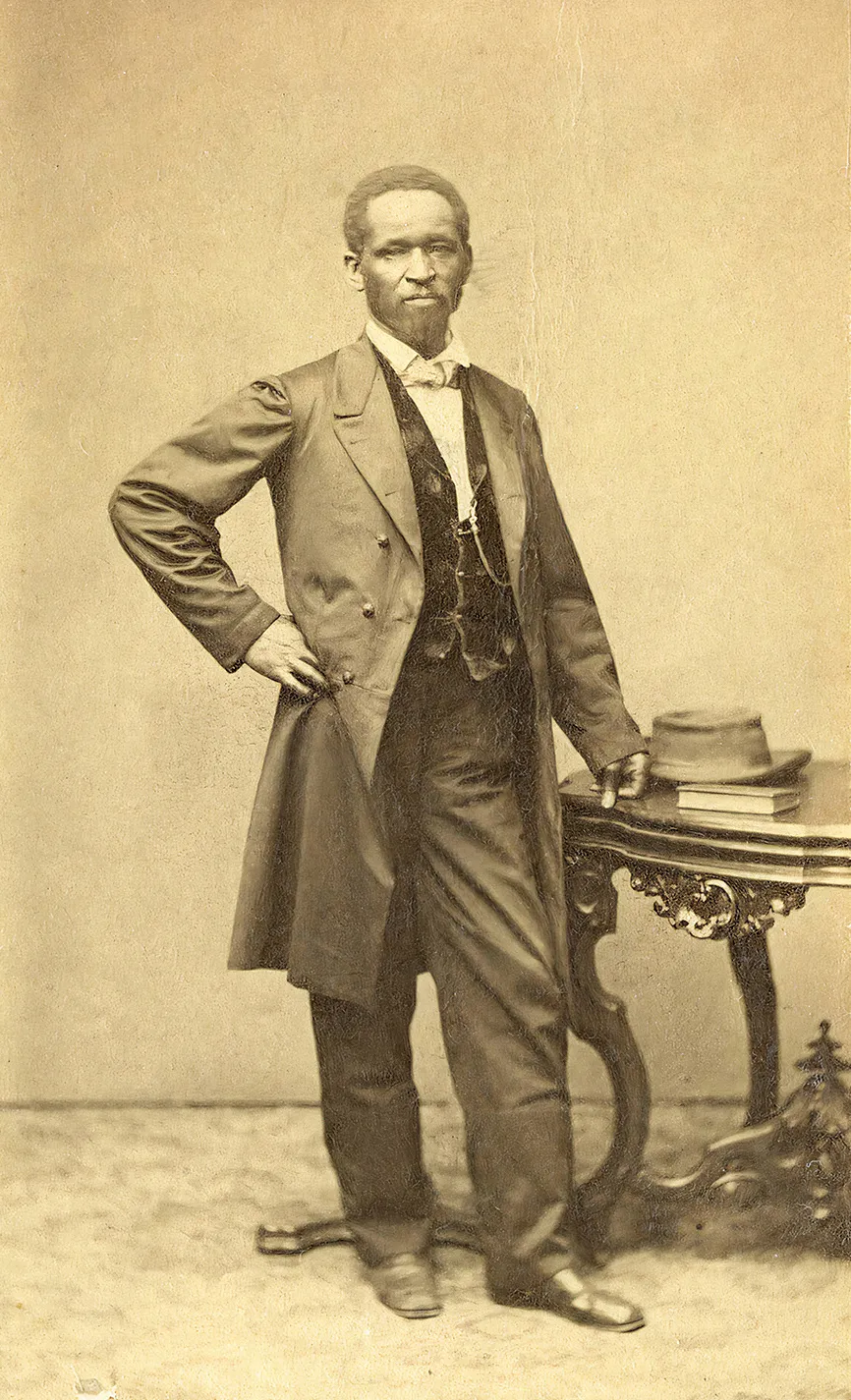

As the club grew, it embraced a startling diversity. Large numbers of immigrants began to join, including Germans and Swedes, Lutherans and Jews, and even some Catholics. Here and there, young women formed “Wide Awake auxiliaries.” Brave Republicans organized companies in cities like Baltimore, St. Louis and Washington, D.C. that were notorious for their violent, pro-slavery street gangs. Perhaps most surprisingly, African American men started to join. At a time when virulent racism tainted even the antislavery Republican Party, this was a bold step. Black leaders formed a new company in Oberlin, Ohio, and fugitive slaves and abolitionist leaders launched another in Boston. Centuries later, with the benefit of many hard-won civil rights victories, modern Americans can hardly grasp how jarring and powerful it must have been to see columns of African American men marching in military uniforms down Boston’s midnight streets.

Yet few of these Wide Awakes seemed to grasp the full impact of their movement. Most focused on power struggles with local Democrats and barely considered what their fellow citizens in the South might think, viewing that distant part of the country as a Slave Power abstraction. They certainly didn’t empathize with those who worried about the rise of uniformed political militias in the North. One California newspaper dismissed such worries, writing that the whole movement came from “some shrewd Yankee, who invented a cheap uniform,” insisting “there is no warlike intention whatever in the movement.”

But millions of Southerners saw an army of destruction training in the night, fears inflamed by the country’s partisan newspaper networks, which spread deliberate disinformation and secessionist plots. As the election heated up in September and October, Southern papers began to fret about this massive midnight rising, creating a hysteria about the Wide Awakes. In Virginia, one editor insisted that Wide Awakes hid rifles under their capes. In Georgia, another alleged that they were plotting “wild orgies of blood, of carnage, lust and rapine.” Young men in Charleston, New Orleans, Baltimore and even Washington, D.C. began to form their own paramilitary companies, calling themselves “an offset” to the Wide Awakes.

Trying to explain to Northerners how ominous the movement seemed, Kentucky-born New Yorker George N. Sanders published a warning days before the November election. It didn’t matter, Sanders insisted, that Lincoln was a moderate politician. Nor would it matter, in the event of his victory, whether he chose conservatives for his cabinet. “The South looks to your military and militant Wide Awakes, to your banners, your speeches, your press and your votes, and not to what Mr. Lincoln may say or do after his election,” Sanders wrote.

Up in Hartford, Eddie Yergason barely noticed. He was no longer a lowly 19-year-old clerk. He was a “Hartford Original.” As the campaign raced toward Election Day, his company was feted at parties, and he wrote home bragging about grand receptions and giant frosted cakes served by local ladies. “They think every thing of the Original Wide Awakes,” he beamed. Enjoying the attention, Yergason had little sense of what was coming.

November 6, 1860, was probably the most significant Election Day in American history. It drew among the highest turnouts ever recorded—81.2 percent of eligible voters went to the polls, and tens of millions more people watched anxiously from the sidelines. Wide Awakes welcomed the dawn with fireworks and cannon fire, then spent the day “patrolling” polling places across the North. Depending on how you planned to vote, they were either protecting democracy—or intimidating rivals.

When all was done, Lincoln sat anxiously in the telegraph office in Springfield. Companies of Illinois Wide Awakes stood at attention outside. News came slowly along the wires. Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut and nearly every “doubtful” state had voted Republican.

Lincoln had won an awkward 39.8 percent plurality of the popular vote in a four-way race, but fully three-fifths of the Electoral College. Frederick Douglass called it a revolution. For generations, he wrote, “the masters of slaves have been masters of the Republic.” But Lincoln’s victory had “broken their power. It has taught the North its strength, and shown the South its weakness.”

And that Northern strength, to many, looked like the Wide Awakes. The Republicans, after all, had performed best in states where the movement was largest, among exactly the kind of young, laboring moderates the Wide Awakes mobilized. In the final assessment of the New York Tribune, the most popular Republican newspaper, the election was decided by the Democratic Party’s internal divisions and by the massive Wide Awake movement. That organization “embodied” the Republican cause, the Tribune argued, becoming a concise symbol for millions who hated the Slave Power.

No wonder, then, that the companies also became a useful symbol as the nation hurtled from election to war. As some Southern states began to reject the election’s outcome and prepared to secede, leaders invoked the hated club from Hartford. In the U.S. Capitol, Texas Senator Louis Wigfall accused his Republican colleagues of organizing the “politico-military, John Brown Wide Awake Pretorians to sweep the country in which I live with fire and sword.” According to some secessionists, the Wide Awakes had already broken the compact that held the states together. A democracy in which such a movement won elections was not worth staying in, the argument went. When South Carolina seceded, a little more than a month after Lincoln’s victory, members of its secession convention invoked “the Wide Awakes of the North” on their way out of the Union.

Meanwhile, the Wide Awakes refused to melt away like campaign organizations were supposed to do. Some Republicans talked about continuing to meet on “a permanent political basis.” Others looked at the thousands of trained, uniformed young partisans and saw an actual army, not a symbolic one. As Republicans worried about attacks on Lincoln’s inauguration, Wide Awake hotheads talked of going to Washington to protect their candidate. One letter to Lincoln promised: “If you say the word, I will be there with from 20 to 1,000 men … organized and armed.” That note came from George Bissell, who had first admired Eddie Yergason’s cape. He was again sending them to the front with a swing of his floppy white hat.

Lincoln wisely discouraged this escalation. He sent a letter to Sperry, thanking the Hartford Wide Awakes for their “great services,” but implied their work was done. The organizer of Lincoln’s trip from Springfield to Washington publicly asked Wide Awakes to disperse. Lincoln’s young secretaries put the word out to their friends among the Springfield Wide Awakes: Don’t go to Washington. The threat to Lincoln’s life, as history would prove, was real; another leader might have eagerly marched to the capital with tens of thousands of partisan fighters. But the president-elect prioritized maintaining the union and not ostracizing moderates, and he left these bodyguards at home.

And yet, as the inauguration neared, strangers with Yankee accents (and revolvers in their pockets) started to appear in the capital’s boarding houses. When Lincoln finally rode down Pennsylvania Avenue to accept the presidency and deliver his stirring inaugural address in March 1861, hundreds of plainclothes Wide Awakes filled out the crowds around him, including James Chalker, the Hartford Originals’ fighting captain.

Just over a month later, Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor. That bombardment sparked the war but killed no one. The first real bloodshed came from two clashes involving the Wide Awakes. On April 19, 1861, the National Volunteers, a pro-Southern Democratic militia organized in Baltimore and Washington in response to the Wide Awakes, attacked Massachusetts troops marching through Baltimore, killing several. Not long afterward, armed Wide Awakes in St. Louis captured all 800 members of a Democratic militia who were accused of Confederate leanings, and fired on the crowd around them, killing 30 people.

Wide Awakes raced to join the Union Army. Whole companies enlisted together in the war’s first weeks. Estimates are shaky, but perhaps three- quarters of the nation’s Wide Awakes fought in the war, exceeding the 50 percent of Northern men who served. The Hartford Originals were the epicenter. Sperry, Bissell, Chalker and about seven-tenths of their company’s officers enlisted, many right as the war began in April and May 1861. Four of the five Talcott boys fought.

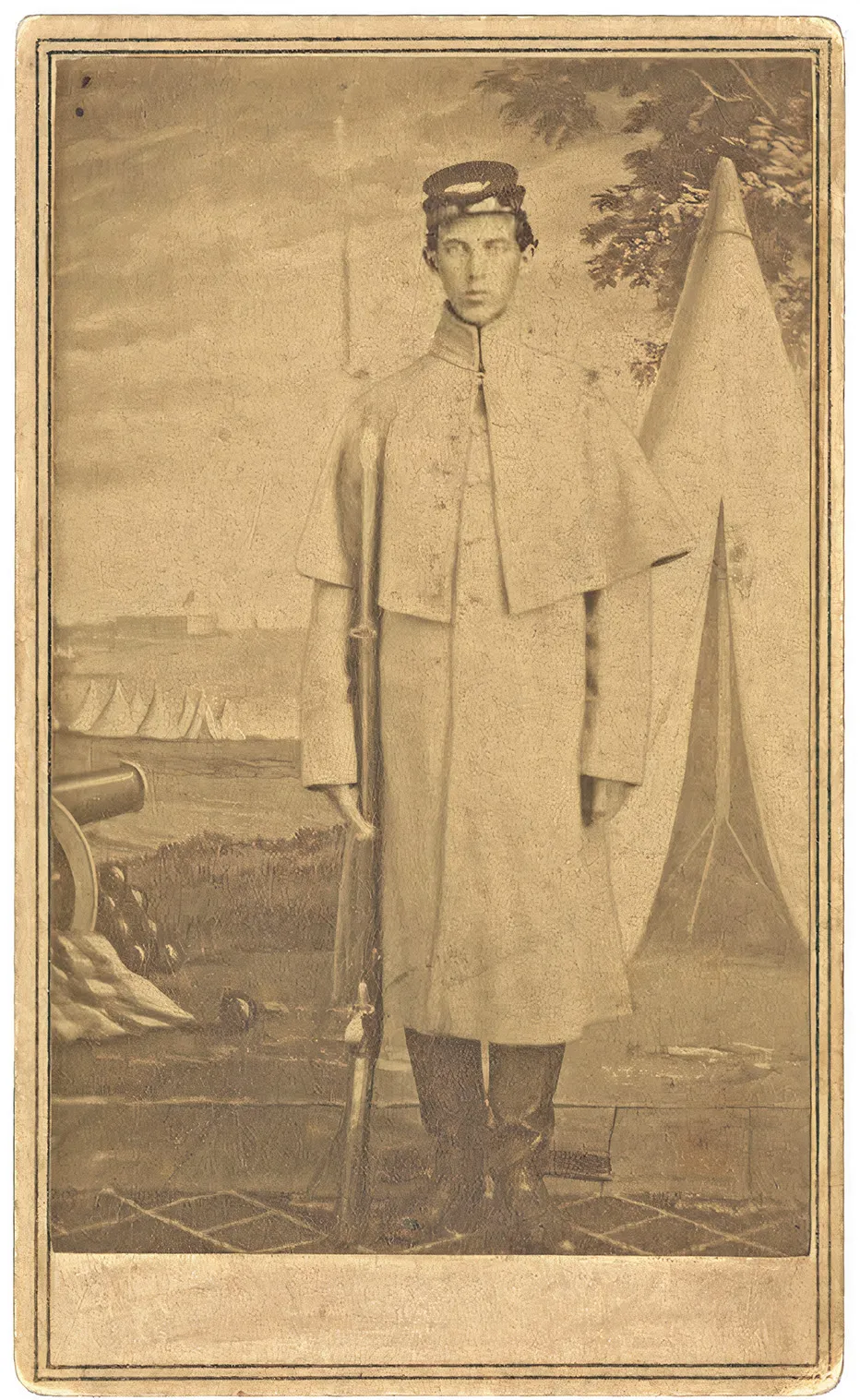

And Eddie Yergason? He wrote to his mother that he planned to enlist. She wrote back a stern letter, telling him not to “do anything rashly,” pleading for him to “appreciate your mother’s feelings, no one on the broad earth cares for you as much as your mom.” He waited a year, then enlisted in Connecticut’s 22nd Regiment. A photograph shows him as still basically a kid, a skinny wraith with piercing dark eyes swallowed up by an army greatcoat.

The Union Army benefited from the Wide Awakes, but their service also unmade the movement. During the chaotic and conspiratorial 1850s, Wide Awake militarism made sense. It was orderly in a mob democracy, vigilant in a world haunted by cabals. But with the nation fighting an actual war, who would want to play dress-up as a soldier?

The movement left a legacy, though. For a half-century after the 1860 election, uniformed and torch-bearing marching companies became the dominant form of campaigning for all political parties. The club’s style remade American democracy as participatory and performative, an accessible spectacle anchored in mass partisanship. And it all grew from a handful of symbols: capes to unify diverse coalitions, torches to light the dark corners against conspiracies and marching orders sending masses off against a common enemy.

It took decades for Yergason to fully grasp what he had done. After creating the first cape, he fell into the background of the original club, not old or well-established enough to win election as an officer. But at Gilded Age reunions, he could finally appreciate his contribution. He started to show off the original cape he had sewn and published letters in the Hartford Courant, explaining that “I was the first one to wear a cambric cape … with four other young men—we originated the Wide Awakes.” Other members affirmed Yergason’s version of events.

And who was this Edgar S. Yergason, writing to editors, reminiscing at banquets? He no longer slept on a cot in the Talcott & Post’s store. The young man with an eye for the striking visual detail had risen to become one of America’s most successful designers. He curated interiors for Theodore Roosevelt and Thomas Edison. President Benjamin Harrison, who was also said to have been a Wide Awake, invited him to redecorate the White House. Yergason enlivened that old mansion with electric lighting, bold color schemes and modern window treatments. Can it be a coincidence that the boy who launched such a visually composed political movement grew up to be a celebrated designer?

Not many people remember Yergason, unlike the generals who fought the war and were memorialized afterward. Recalling the Civil War in purely military terms has helped Americans distance themselves from the hardest questions it posed: how citizens could go to war with each other, how racism poisoned our republic, how the political system we herald led to such carnage.

But Yergason and his cape are apt reminders of how our political symbols capture both what is most motivating, and most terrifying, about our democracy. The young clerk looked around a textile shop and found the tools to express the hopes and fears of millions of Americans. Most of the time, people can distinguish between a symbol and a threat. For a democracy on the brink, that distinction vanished. Perhaps more than any icon in the history of American politics, Eddie Yergason’s cape fit.

Adapted from Wide Awake by Jon Grinspan. Copyright © The Smithsonian Institution, 2024. Used by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing.