What is a shoebill?

Depending on your perspective, a shoebill either has the same goofy charm as the long-lost dodo or it looks like it might go on the attack any moment.

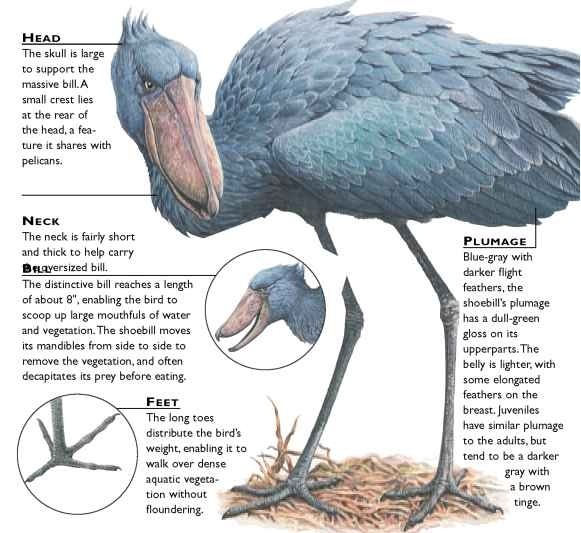

What makes the aptly named shoebill so unique is its foot-long bill that resembles a Dutch clog. Tan with brown splotches, it’s five inches wide and has sharp edges and a sharp hook on the end. Its specialized bill allows the shoebill to grab large prey, including lungfish, tilapia, eels, and snakes. It even snacks on baby crocodiles and Nile monitor lizards.

At first glance, shoebills don’t seem like they could be ambush predators. Reaching up to five feet tall with an eight-foot wingspan, shoebills have yellow eyes, gray feathers, white bellies, and a small feathered crest on the back of their heads. They also have long, thin legs with large feet that are ideal for walking on the vegetation in the freshwater marshes and swamps they inhabit in East Africa, from Ethiopia and South Sudan to Zambia.

Shoebills can stay motionless for hours, so when a hapless lungfish comes up for air, it might not notice this lethal prehistoric-looking bird looming until it’s too late. The birds practice a hunting technique called “collapsing,” which involves lunging or falling forward on their prey.

Shoebills are in a family all their own, though they were once classified as storks. They do share traits with storks and herons, like the long necks and legs characteristic of wading birds, though their closest relatives are the pelicans.

Though they’re mainly silent, shoebills sometimes engage in bill-clattering, a sound made as a greeting and during nesting. They keep cool with a technique called gular fluttering—vibrating the throat muscles to dissipate heat. Chicks sometimes make hiccup-like sounds when they’re hungry.

Reproduction

Shoebills reach maturity at three to four years old, and breeding pairs are monogamous. These birds are very solitary in nature, though, and even mating pairs will feed at opposite sides of their territory. Breeding pairs build nests on water or on floating vegetation, and can be up to eight feet wide. Females lay an average of two eggs at the end of the rainy season.

As co-parents, both birds tend to the eggs and young. This includes incubating and turning eggs, and cooling them with water they bring to the nest in their large bills. Hatching occurs in about a month. Chicks have bluish-gray down covering their bodies and a lighter colored bill. Only one chick typically survives to fledge.

Conservation

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature estimates that there are only between 3,300 and 5,300 adult shoebills left in the world, and the population is going down.

As land is cleared for pasture, habitat loss is a major threat, and sometimes cattle will trample on nests. Agricultural burning and pollution from the oil industry and tanneries also affect their habitats. Shoebills are hunted as food in some places, and in others, they’re hunted because they’re considered a bad omen.