When we think of ancient artifacts, we usually think of the objects that people held dear. But if you really want to get the dirty details of daily life in antiquity, you should check out the things that have been discarded.

There is perhaps no better example of this than the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, a ground-breaking collection of texts (amounting to at least half a million fragments), that were discovered in ancient Egyptian trash heaps at the end of the 19th century. From food orders to sacred scriptures, the discoveries at Oxyrhynchus paint a picture of ancient life that might surprise you.

The Ancient City of Oxyrhynchus

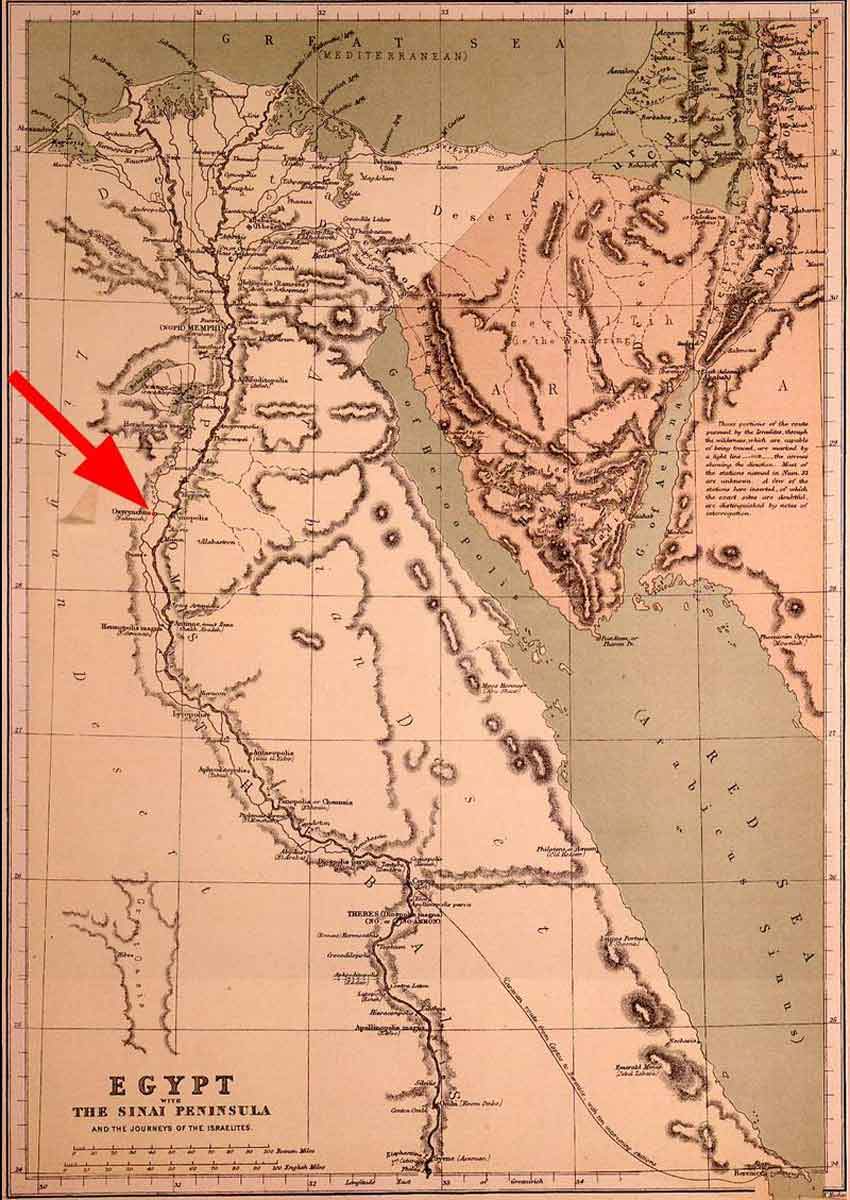

In Egypt’s Western Desert, on the bank of the Bahr Yussef, sits the site of the ancient city Oxyrhynchus. Once called Per-Medjed, after the sacred elephantfish of the Nile, the city was the capital of the 19th Upper Egyptian nome.

When Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in 332 BCE, Greek citizens populated the city, and renamed it Oxyrhynchou polis, “City of the Sharp-snouted Fish.” The city remained a flourishing regional capital throughout the Ptolemaic era and during Roman rule. The town had a grand theatre, public baths, a gymnasium, and temples to gods such as the Greco-Egyptian deity Serapis. It was surrounded by farmland and irrigated by the annual flooding of the Nile. As Christianity took hold across the region in the 1st century CE, Oxyrhynchus also became known for its many churches and monasteries.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

The city steadily declined throughout the Byzantine and Arab periods, eventually falling into ruin. Most of its structures were built over and transformed into the modern village of el-Bahnasa. But the glory days of Oxyrhynchus were not entirely behind it. During the British occupation of Ottoman Egypt in the late 1890s, two young archaeologists made a discovery that thrust Oxyrhynchus into the global spotlight and secured its place as one of the most significant sites in history.

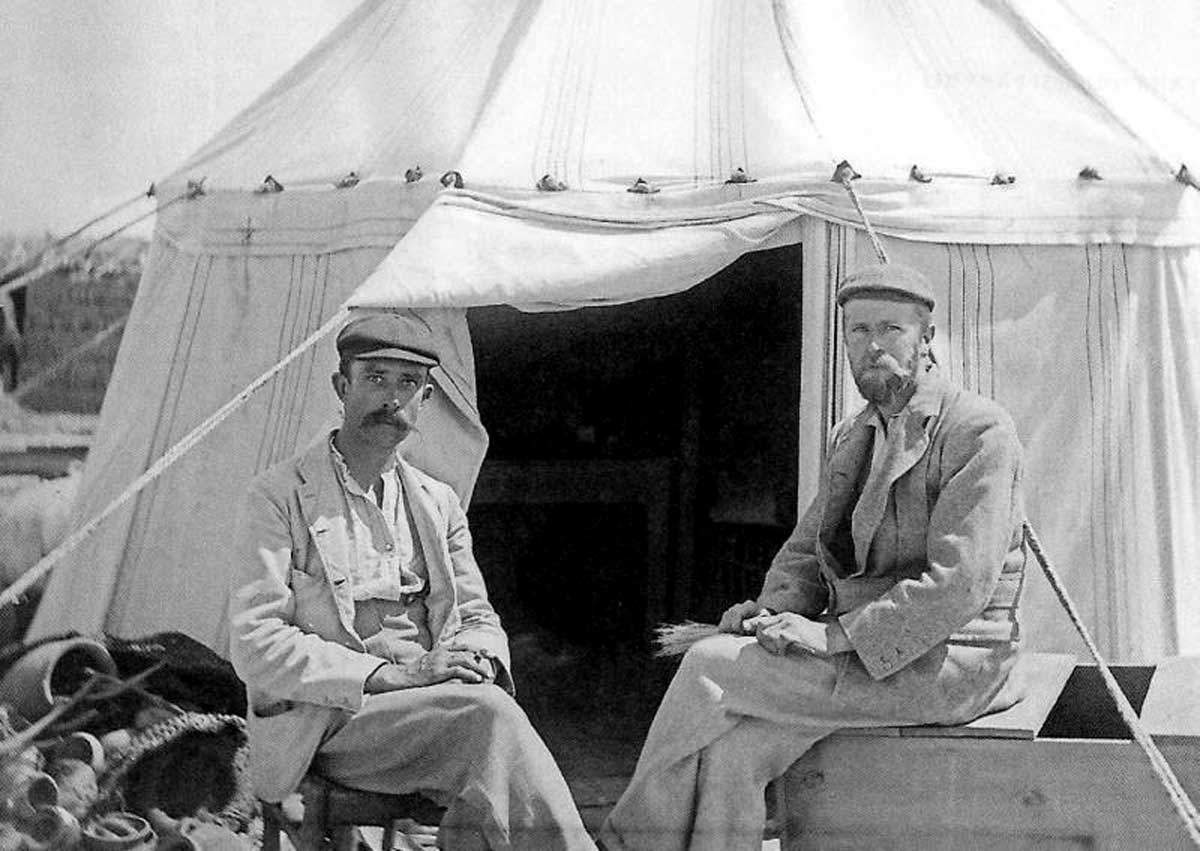

The Excavators: Dreaming of Papyri

Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt of The Queen’s College, Oxford dreamed of uncovering great Greek masterpieces lost to time. Backed by the new Greco-Roman branch of the Egypt Exploration Fund, they set their sights on Oxyrhynchus.

Grenfell had an inkling that it was a promising site for Greek manuscripts. Since it was a prominent capital city, it must have been home to many wealthy people who could afford to keep libraries of literary texts. It was also possible that they might find some early Christian literature, given the number of churches and monasteries once present at the site.

When Grenfell and Hunt arrived at the site in the winter of 1896, it did not look as promising as they had imagined. The surviving structures of the town were not well-preserved. Most of the houses and buildings were cleared down to their foundations and were not likely to turn up anything valuable. They hoped to find something exciting in the Greco-Roman cemetery to the west of the town. Some of the most exceptional Greek literary rolls had been found buried with their owners in their tombs. Unfortunately, their excavation of the cemetery did not live up to their expectations.

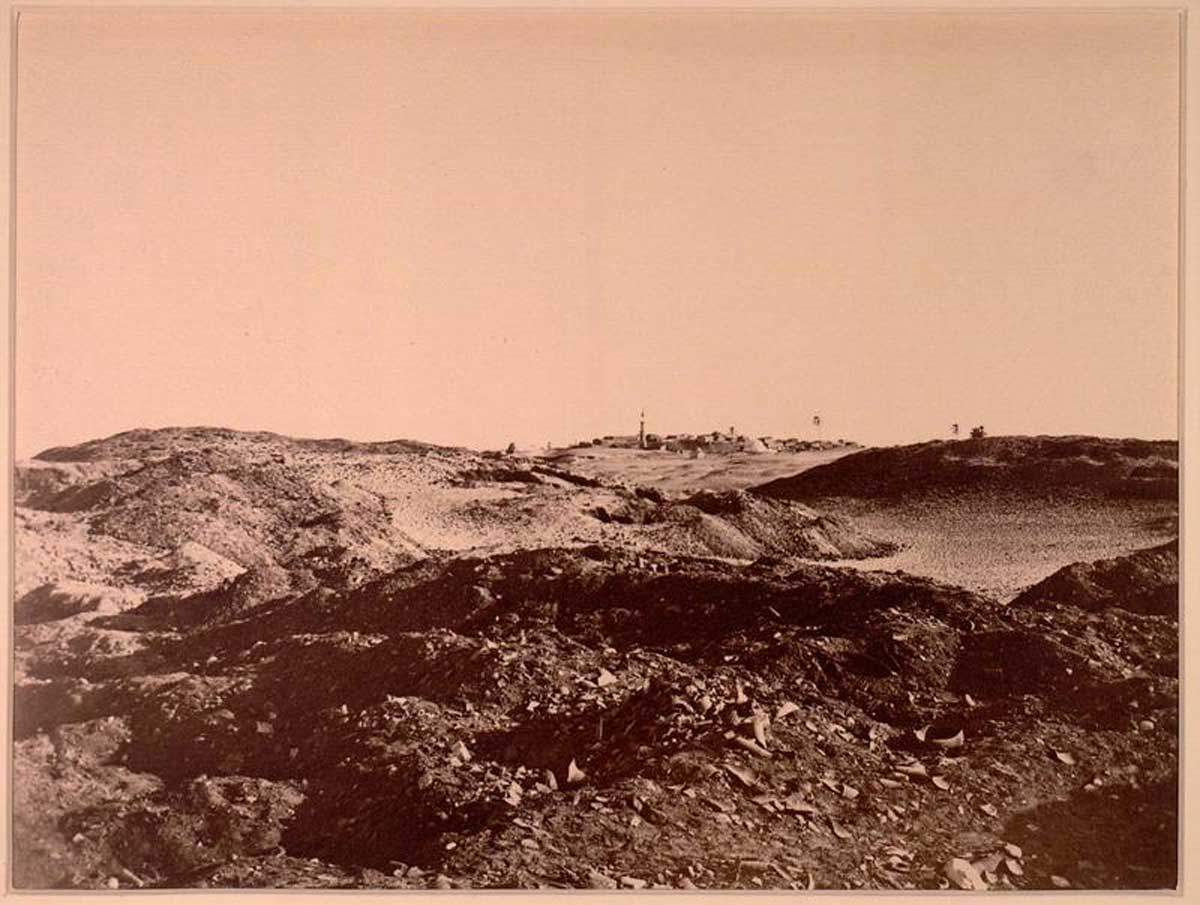

Their next best bet was to dig into the mounds just outside the town, where the city’s ancient occupants dumped their trash. The findings in these mounds were likely to be less valuable, and in worse condition, due to the simple fact that they had been purposefully discarded. However, they soon discovered that these rubbish mounds were far more impressive than your average garbage dump.

The Excavation: A Torrent of Papyri

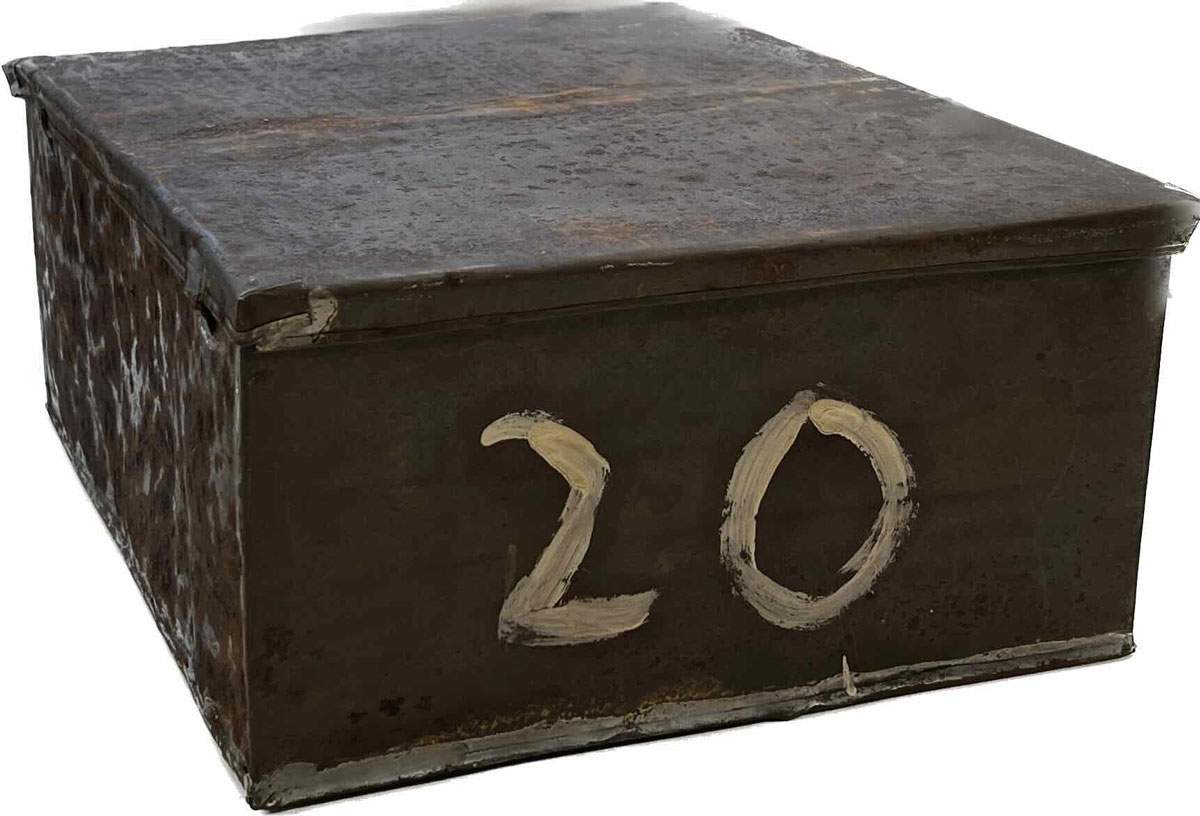

Grenfell and Hunt set local workers to work digging trenches in the side of one of the low rubbish mounds. That’s when the papyri started flowing. In his archaeological report of their excavations, Grenfell famously wrote that “the flow of papyri soon became a torrent which it was difficult to cope with.” They had two men begin to make metal tins to keep papyrus fragments found in the same area together. For the next ten weeks, the men making the tins could hardly keep up with the number of papyri uncovered from the mounds.

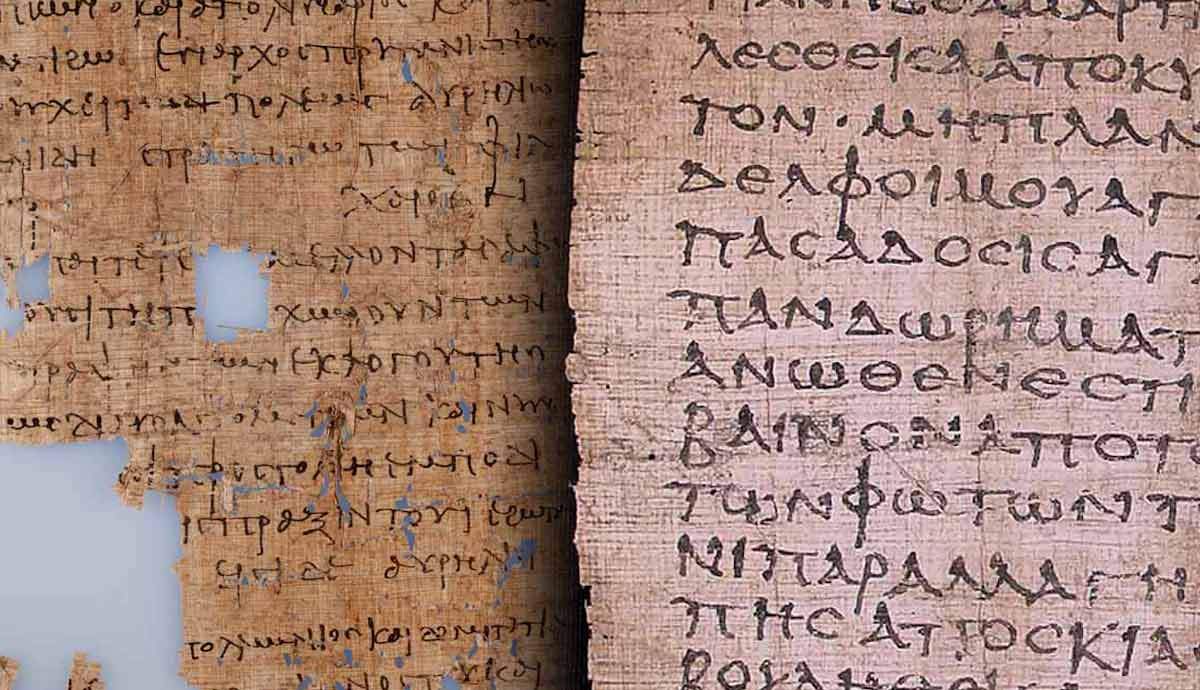

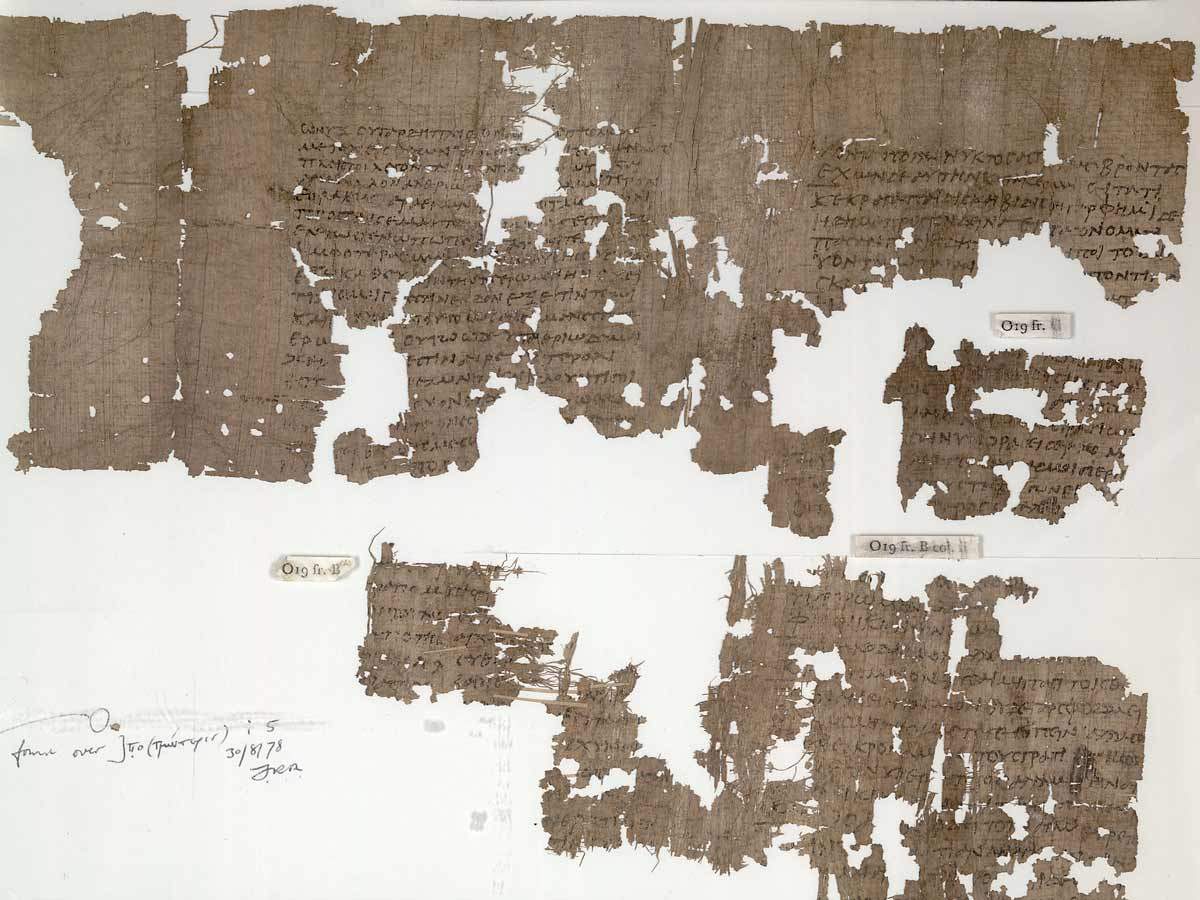

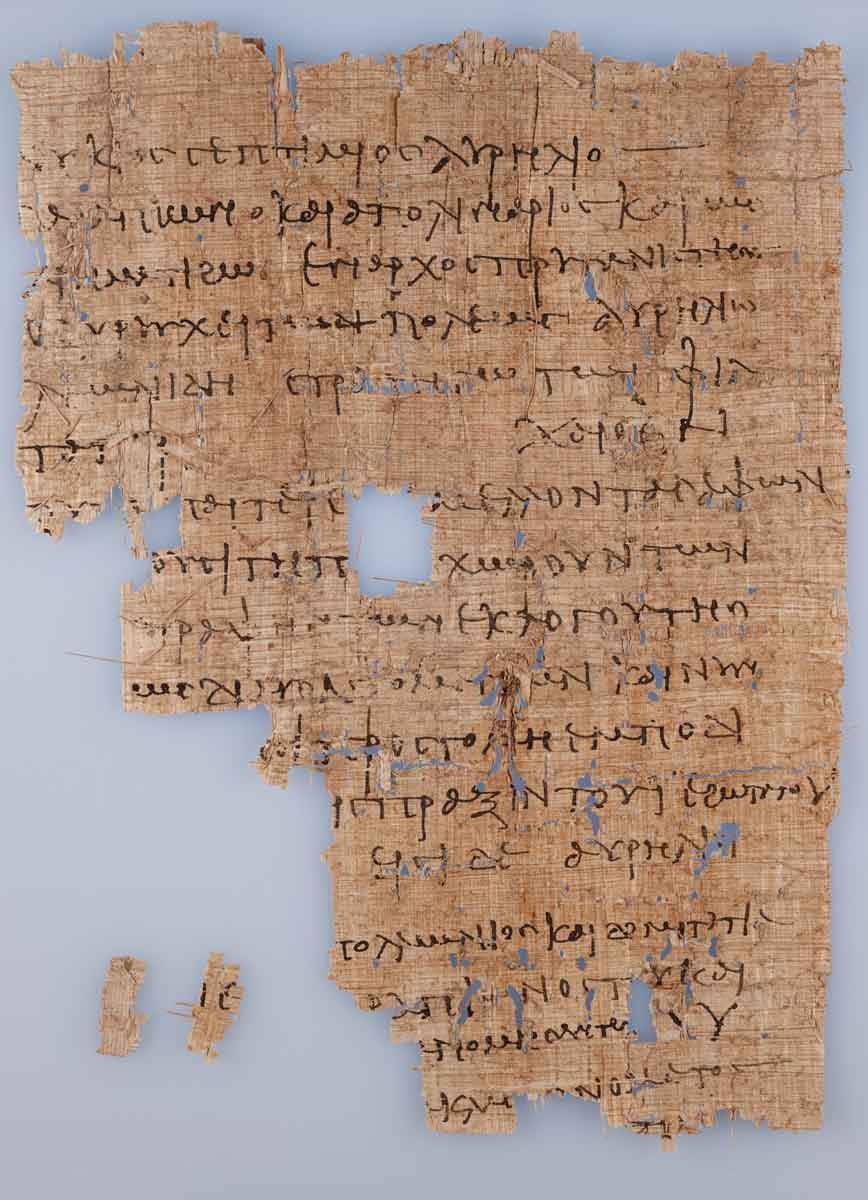

The region’s dry climate, combined with the sheer amount of material dumped there over time, had preserved an unprecedented amount of ancient papyrus. Throughout the course of their work between 1896 and 1907, Grenfell and Hunt’s excavations uncovered about half a million papyrus fragments, from small scraps to full-sized rolls. Most of the collection is written in Greek, but other languages present include Latin, Coptic, and Arabic. It is the largest collection of ancient papyri in the modern world.

The Literary

It is safe to say that Grenfell and Hunt fulfilled their dream of unearthing great masterpieces of Greek literature. The literary papyri, which only make up about one-tenth of the entire collection, consist of both well-known Greek classics and a few long-lost works. The roster of ancient poets, mathematicians, historians, and dramatists includes household names such as Homer, Plato, and Aristotle. The mounds at Oxyrhynchus also revealed several previously unknown texts, lost in the Middle Ages, and greatly expanded versions of works we know and love. We can thank Oxyrhynchus for the comedies of Menander, the poetry of Sappho, and one of the oldest extant diagrams from the father of geometry, Euclid.

The Theological

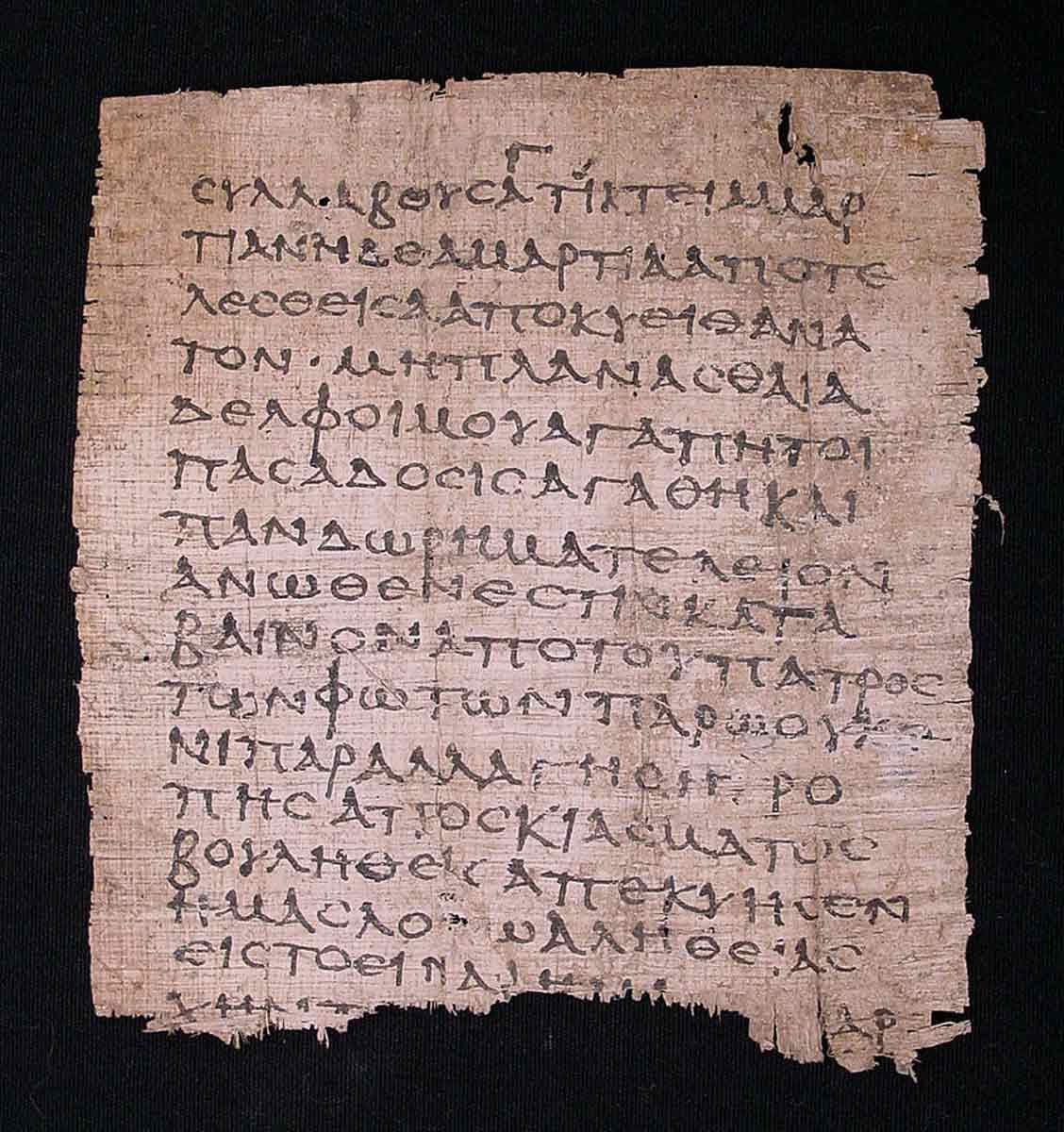

There were also a great number of theological texts uncovered at the site, including fragments from the Septuagint, the New Testament, and apocryphal texts. The discovery of these texts has been hugely influential for the field of New Testament and early Christian studies. They are some of the earliest Christian texts ever discovered and they shed light on ancient scriptural traditions.

One of the first significant finds from Grenfell and Hunt’s excavations was a leaf from a book containing sayings of Jesus, some of which had never been seen before. There are fragments from the four canonical gospels of the New Testament, as well as extracanonical literature like the Gospel of Thomas, the Acts of Peter, the Acts of Paul and Thecla, and The Shepherd of Hermas. There is also an abundance of other Christian material, including prayers, amulets, and letters.

The Non-Literary

Most of the texts that have survived from antiquity are precisely the kind of impressive works that Grenfell and Hunt were hoping to find at Oxyrhynchus. Popular literature, scripture, and accounts of powerful people survive through the years because they are copied and circulated so often or are purposefully preserved. However, one of the things that makes the Oxyrhynchus Papyri so unique is that most of the collection is comprised of non-literary documents, detailing the mundane affairs of ordinary people.

The non-literary items discovered at the site are vast and varied. They are an assortment of nearly every kind of document composed in public and private spheres across the centuries: receipts, registrations, orders, disputes, wills, personal letters, school exercises, horoscopes, and more. Grenfell reported certain mounds where the quantity of papyri was so great that it is likely evidence that portions of the local archives were thrown away in bulk. These documents have provided scholars with a uniquely in-depth picture of this ancient city, from the structure of government, to the routines of ordinary people.

Government documents such as edicts, court-orders, and tax records supply scholars with invaluable information concerning the political and economic landscape of the region. More private correspondences, such as letters and invitations, provide a glimpse into the social scene at Oxyrhynchus. One such invitation from the 2nd or 3rd century CE reads, “Ammonios asks you to dine at the banquet of the lord Serapis in the dining hall of the Serapeion on the 9th, beginning from the 9th hour.” Though these non-literary documents are certainly less showy than the literary and theological texts of Oxyrhynchus, they are no less important to the study of the ancient world.

Impact: The Value of Garbage

Grenfell and Hunt published the first texts from the Oxyrhynchus Papyri in 1898. Since then, people have continued to uncover, analyze, and publish the fragments unearthed from the mounds of Oxyrhynchus. The papyri were distributed by the Egypt Exploration Fund (now Society) but much of the collection resides in Oxford’s Art, Archaeology, and Ancient World Library.

Modern scholarship on the Oxyrhynchus Papyri reflects a major shift in the fields of Classics and New Testament studies. Many scholars are reassessing questionable trends in their fields, such as the privileging of certain texts over others based on their significance in modern culture and religion. What does it mean that sacred texts and beloved classics were thrown away in the same mounds as wheat orders, corn payments, and registrations of goats and sheep?

By placing the glamorous works of history in the context of a garbage dump, scholars can study ancient texts on their own terms, with less bias toward works with modern influence or sanctity. For example, AnneMarie Luijendijk, a New Testament scholar and papyrologist, is interested in what she calls “the death of the codex,” or “the damage, disinterest, and disposal of Christian manuscripts” at Oxyrhynchus. This incredible collection of papyri continues to open up exciting new avenues of study, which demonstrate both the treasures to be found in the trash and the trashy side of modern treasures.