Few faces are as iconic as that of Nefertiti. The bust uncovered in 1912 cemented her as one of the most recognizable historical figures to ever live. However, behind that image is one of the most fascinating and unique players in Egyptian history. Her story is every bit as enchanting as the timeless art that has made her so famous but also one that is mired with uncertainty and differences of interpretation, which means no two reconstructions of her life are the same. However, we can draw a general picture of this fascinating woman.

Married to the legendary heretic Pharaoh Akhenaten, together they instituted a religious revolution that cast aside Egypt’s old gods and favored the exclusive worship of the Aten sun disc. Although the revolution did not long outlast its instigators, Nefertit’s actions endured as one of the most controversial and hotly debated periods of Egyptian history.

The Beautiful One Has Come

The uncertainty begins with her origins. Nefertiti’s name means ‘The Beautiful One Has Come’, but come from where?

The only concrete thing we know about her childhood is that she had a wet nurse named Tey. Tey was the wife of a prominent courtier called Ay, whose name should be familiar to anyone who has delved into this period before. Ay began his career under Amenhotep III and continued through Akhenaten and his successors, becoming a vizier under Tutankhamun and finally pharaoh after the boy king’s death. Some historians posit that Ay was the brother of Queen Tiye, which explains his high rank and access to the corridors of power.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

It has been proposed that Nefertiti was Ay’s daughter. Inscriptions relating to Ay’s son Nakhtmin imply the existence of an earlier wife who could be Nefertiti’s mother as well. This first wife might have died in childbirth, explaining her absence from the historical record, and Tey took up the role of raising Nefertiti. Additionally, Ay proudly bore the title of ‘God’s Father’, which had often been held by the father of the Queen.

Having Ay as her father would explain how Nefertiti secured such a prestigious marriage while having Nefertiti as his daughter explains Ay’s continued prominence in the royal court.

A Path to Revolution

Wherever she came from, Nefertiti managed to secure a betrothal to Amenhotep IV, the man who would soon become Akhenaten.

Nefertiti first appears in tomb artwork for prominent court officials within the first few years of the reign. These early depictions were already adopting the characteristic features of the Amarna style, such as misshapen skulls, extended limbs, wide hips, and bulging paunches. It was the first hint of the changes to come.

Queens had a duty to provide Pharaoh with children, and Nefertiti was no slouch on that front. Their eldest daughter, Meritaten, was born before the end of year two, and their second, Meketaten, by the end of year four. Their names are a clear sign of their parents’ devotion to their solar deity.

Where this devotion to the Aten came from is unknown. Amenhotep III had favored the Aten towards the end of his life, but Akhenaten’s obsession was peculiarly intense. One might speculate that Nefertiti, the new variable introduced to the royal scene, could be behind it. Alternatively, Akhenaten might have been nursing his intense devotion quietly until he came to power and then unleashed it upon the country.

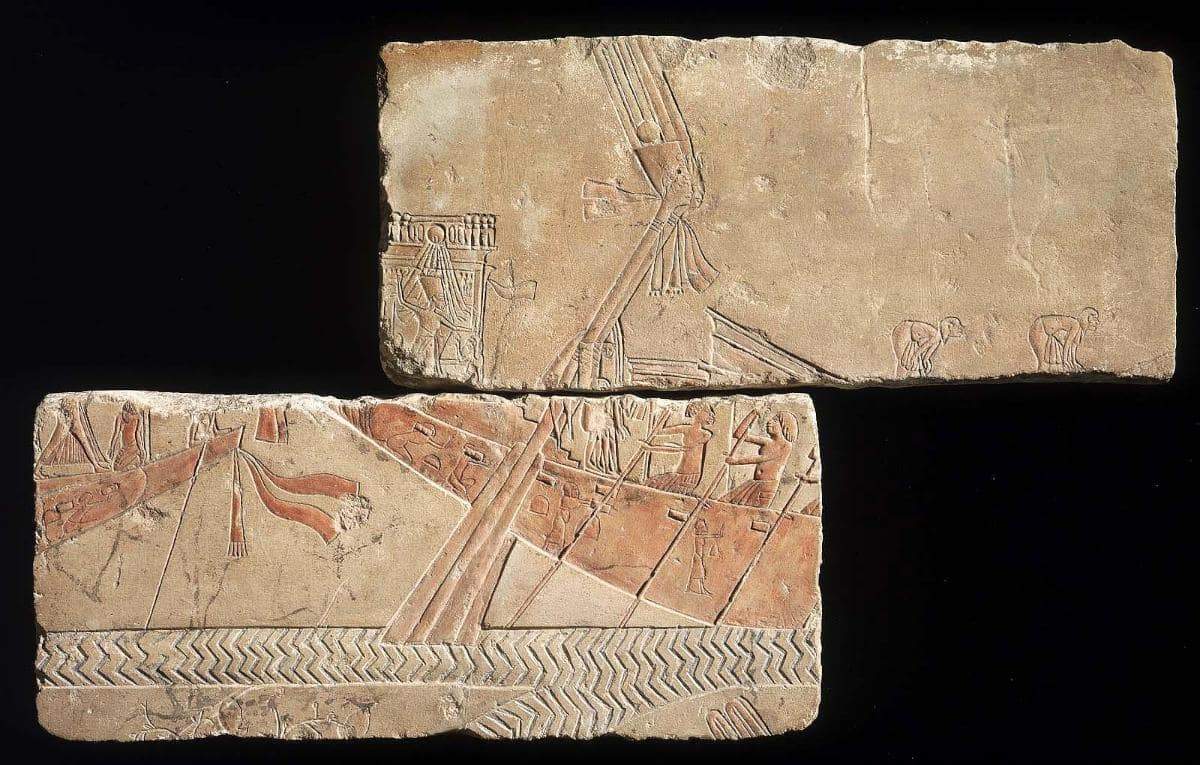

It’s possible that the royal couple was making a statement against the powerful priesthood of the god Amun, which by this point controlled vast amounts of land and wealth. Around year four, they erected a temple to the Aten named the Gem-pa-Aten inside Amun’s sacred temple complex at Karnak. It was a blatant intrusion of the other god’s domain, a snub towards the priests, and a signal that the Aten superseded all other deities.

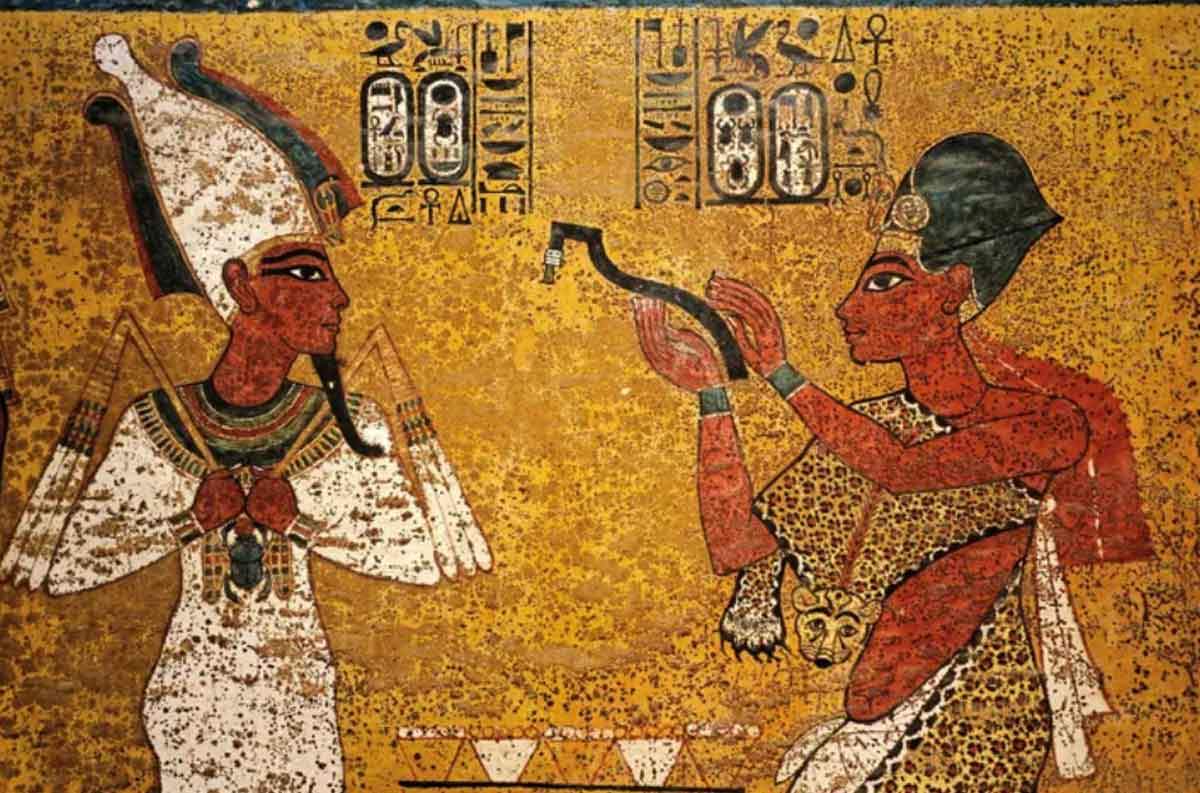

Nefertiti appeared prominently in this temple, as did her daughters. She was shown in some scenes smiting Egypt’s enemies, an act usually reserved for Pharaohs alone. It was a clear statement from Nefertiti and her husband: they were willing to break the rules, and they were only getting started.

Signs of a Struggle?

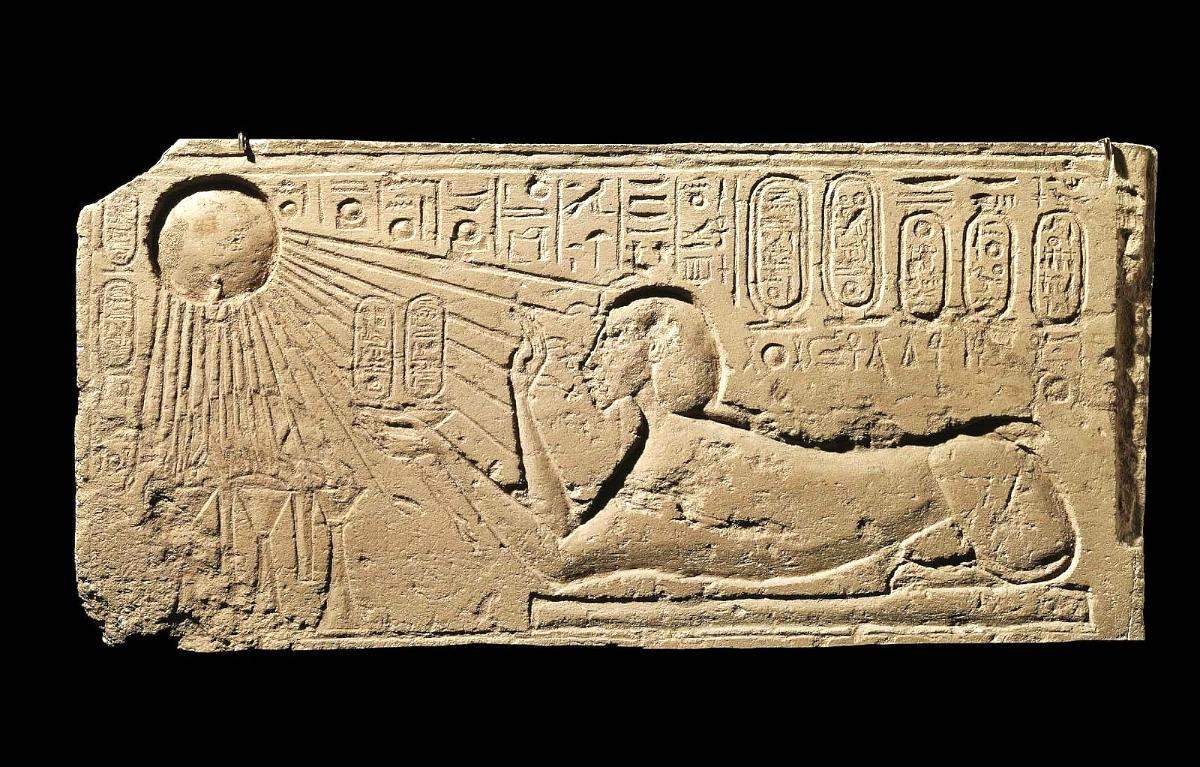

By year five, the Aten revolution was well underway. The royal couple adopted new names to celebrate this — Amenhotep became Akhenaten (One Who is Beneficial to the Aten) while Nefertiti added Neferneferuaten (Perfect Beauty of the Aten) to her name. They also relocated the royal court to a new city at Akhet-Aten, modern-day Amarna.

Boundary stela from Amarna suggest that this move might not have been voluntary. Fragmentary inscriptions allude to Akhenaten’s hearing of ‘terrible things’ that motivated his decision to relocate. Had the people grown tired of the royal couple’s change already? Had the priests of Amun put up a fight? We simply don’t know what happened, only that Akhenaten and Nefertiti left Thebes and, it seems, never returned again.

The Amarna Project

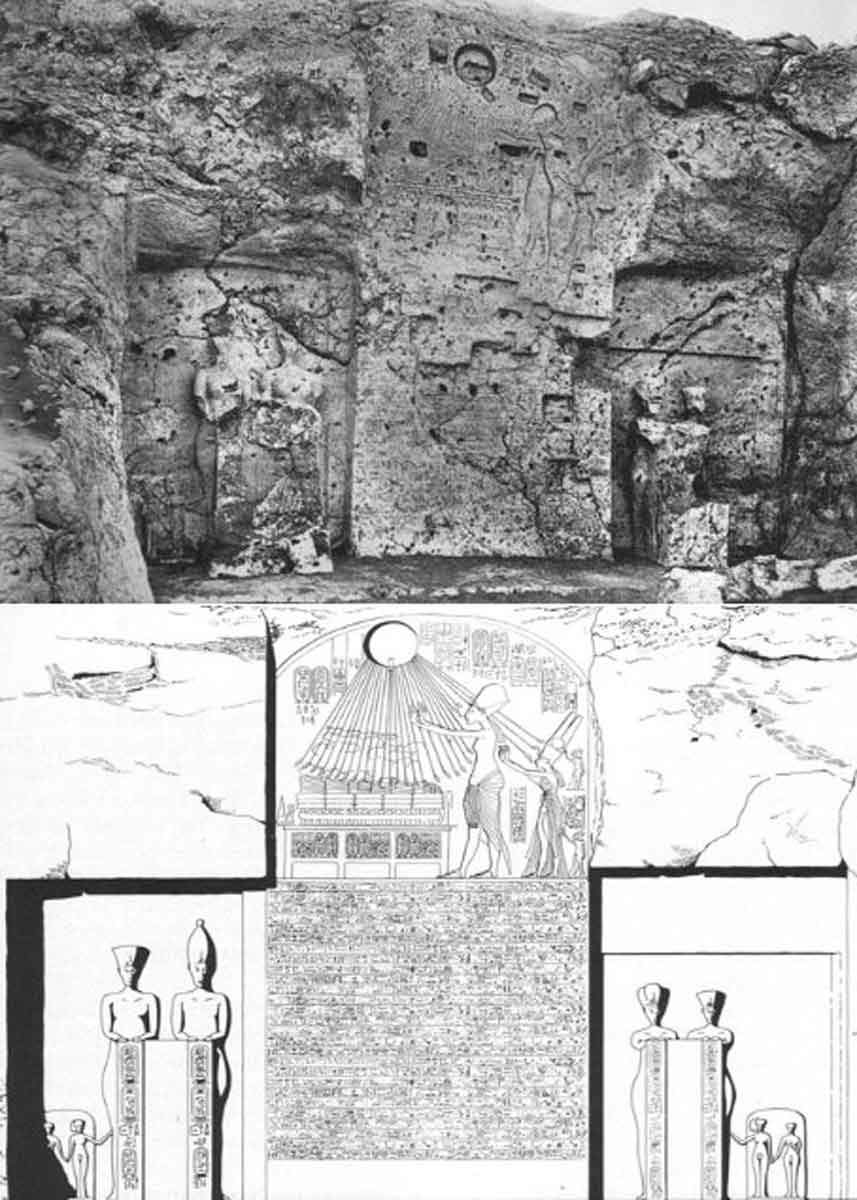

From this new city, Akhenaten and Nefertiti embarked on a radical religious project. Their lavish new city, with its wide open roads and fine noble houses, was also home to sprawling temple complexes and royal palaces. The elites were given marvelous rock-cut tombs around the city, signaling Akhenaten and Nefertit’s commitment to making the city a home for eternity.

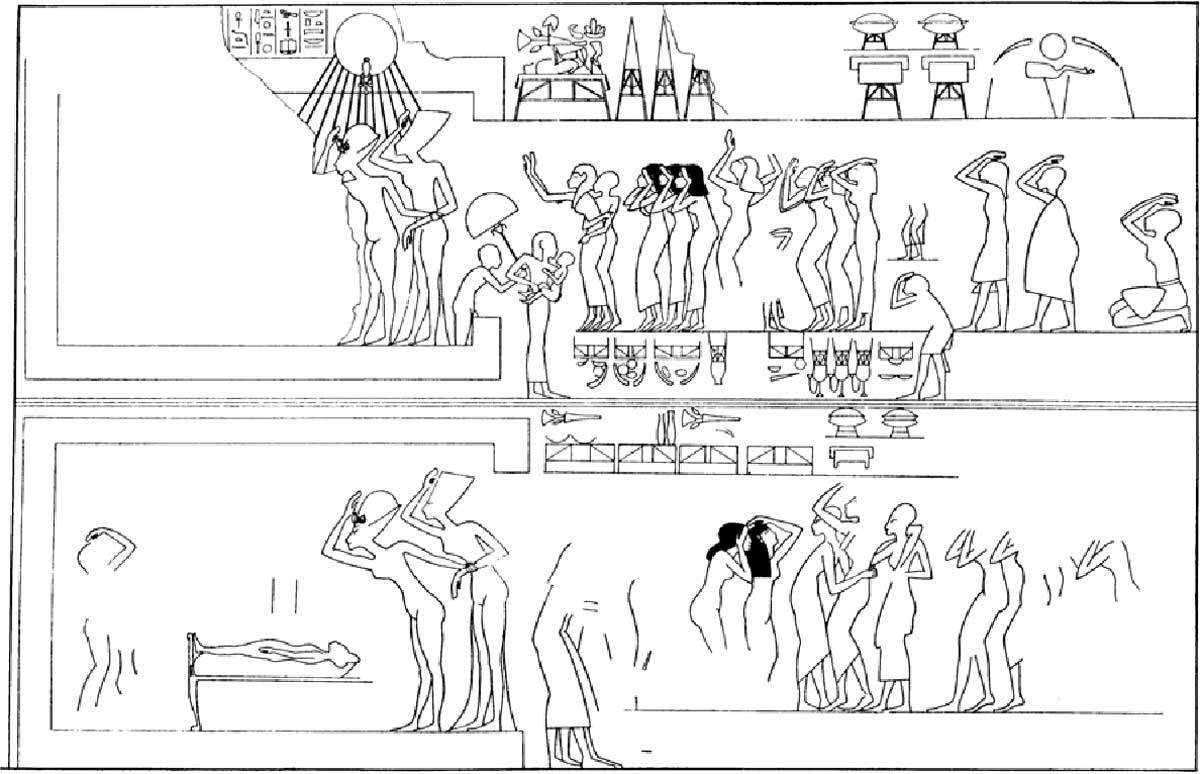

Here, the Amarna art style crystallized. Countless scenes depicted Akhenaten and Nefertiti with their ever-growing royal family. Unlike traditional Egyptian art, all gods save the Aten are absent and instead we see visions of family life. Depictions include Akhenaten and Nefertiti playing with their children or enjoying family meals, a stark departure from the formulaic battle and ritual scenes typical of Egyptian art.

The emphasis on family was amplified by more daughters. Nefertiti gave birth to at least four more at or just before moving to Amarna: Ankhesenpaaten around year 5, followed by Neferneferuaten-Tasherit, Neferneferure, and Setepenre at the new city, all bearing suitably solar names. Debate has also raged over whether Nefertiti bore any sons. The parents of Tutankhamun and the elusive Smenkhkare are a constant topic of debate and, as the Chief Royal Wife, she is a strong candidate. However, there is no particular evidence that makes her their mother. Smenkhkare might well be a brother or nephew of Akhenaten rather than a son, and DNA might favor a union between Akhenaten and one of his sisters as the origin of Tut. Until and unless new evidence emerges, the question of Nefertit’s sons remains wide open.

Nefertiti continued to play a prominent role in public life. She took daily chariot rides with her husband along the city’s main route, which proudly displayed her power while flaunting the traditional prohibition on women riding in such a manner. Nefertiti also appears in scenes bestowing honors upon various officials, placing her at the center of elite politics.

The glory of Amarna culminated in year 12 when the royal couple hosted a dazzling festival there. Dignitaries from foreign lands flocked to Amarna to partake in the feasts and festivities. It might have been to commemorate the completion of the city, or the suppression of a rebellion in Nubia, or perhaps just a whim of the royal couple. Nefertiti and her daughters featured prominently in the celebrations and nobles would later fill their tombs with scenes depicting the momentous occasion.

Amarna seemed to be an idyllic paradise for Nefertiti, but this utopia would soon be shattered by tragedy.

Utopia Shattered

Not long after the year 12 festival, death tore through Amarna.

In less than two years, Neferitt lost at least three of her daughters: Meketaten, Setepenre, and Neferneferure all died. The aged Queen Tiye also passed on. A number of other Amarna figures also suddenly dropped out of the historical record around this period, including Akhenaten’s only known secondary wife, Kiya.

The sudden death or disappearance of multiple people in a short span of time has led to speculation that a plague gripped the city. Some Egyptologists have suggested that it was brought into Amarna by one of the countless foreign visitors during the year 12 festival.

Very little information survives from these final years of Akhenaten’s reign. It appears that work on tombs and temples ground to a halt in the city — possibly a labor shortage caused by the plague or a general collapse in social and economic order.

Nefertiti herself all but vanishes from our sources at this point. In fact, it was long speculated that she had died along with so many others until an inscription mentioning her in year 16 indicated that she survived a while longer.

Succeeding Akhenaten

Akhenaten died after 17 years on the throne. The circumstances and chronology of his death and final years are infamously obscure and have spawned an array of theories.

The ever-frustrating presence of Smenkhkare in the Amarna chronology is the first obstacle. Modern Egyptology is leaning towards Smenkhkare as Akhenaten’s immediate successor, but this is by no means a consensus. If so, then Nefertiti would have been a queen dowager while her daughter Meritaten became full queen.

However, Smenkhkare’s short reign opened the path for a new Pharaoh: Neferneferuaten. The identity of Neferneferuaten has attracted fierce debate but most Egyptologists come down into one of two camps: mother or daughter, Nefertiti or Meritaten.

Neferneferuaten’s name immediately supports Nefertiti, who assumed that name at the same time that Akhenaten took up his Aten name. Nefertiti’s prominence in court and the connections she must inevitably have made from a career at the apex of Egypt’s political system could have easily paved her way into power. Women did not typically rule as Pharaohs, but Nefertiti had been anything but traditional, and women like Hatshepsut had wielded the crook and flail in the past. With Smenkhkare dead and Tut still a young child, Nefertiti could feasibly have assumed power in the meantime.

The identification of Mertiaten as this Pharaoh rests on less stable ground. She was the widow of Smenkhkare but not necessarily more powerful than her mother, given the latter’s longer political career. Neferneferuaten shares some royal titulary with Smenkhkare, which could be an homage from a widow to her husband, but royal titulary had been repeated by Pharaohs in the past. Additionally, many of those who support Mertiaten’s candidacy do so on the assumption that Nefertiti was dead by this point, which is far from certain.

The Nefertiti identification seems more likely, but new evidence could change that.

The Fall of Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti

Assuming she was Pharaoh Neferneferuaten, then Nefertiti’s time at the helm of the Two Lands was be brief. There are very few references to this Pharaoh, and she only ruled for about two or three years.

Nefertiti’s reign might have seen the first steps towards reversing the Atenist revolution. References to scribes of Amun in Thebes during her reign suggest that the proscriptions against the old god of Karnak had been rolled back. An inscription mentions that a mansion of Pharaoh existed in Thebes too, although administration remained in Amarna for her reign.

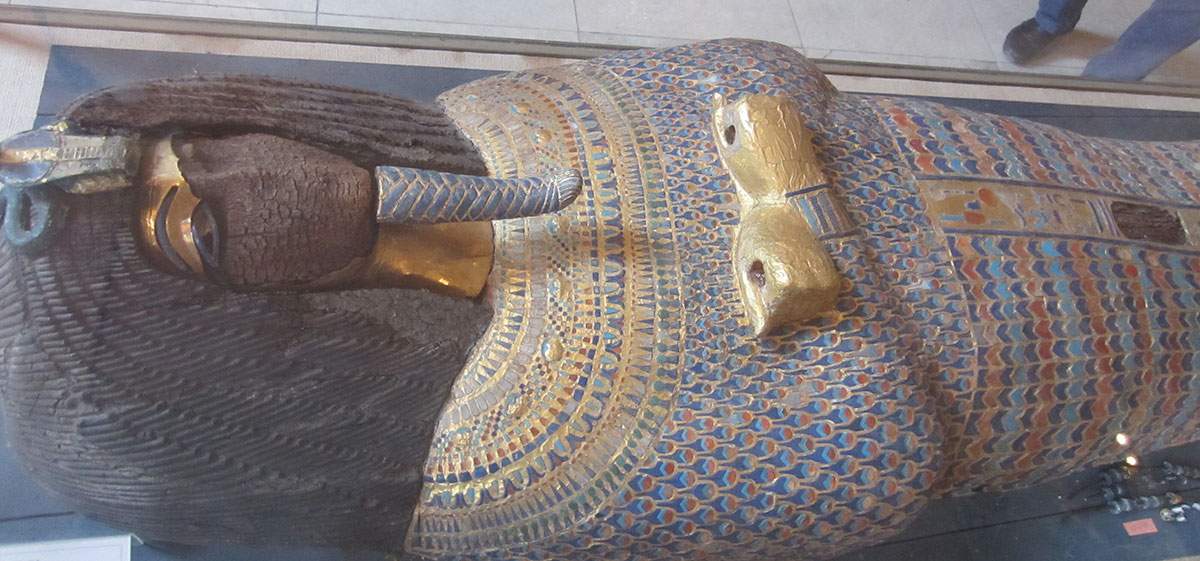

We know nothing of the circumstances of her death. Although her tomb has never been found, many burial goods of Neferneferuaten are known. These goods come almost entirely from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Several items — perhaps including Tut’s iconic burial mask — show traces of Neferneferuaten’s name before being reworked for the boy king.

The reason for this is unclear. The fact that these goods were available suggests they either weren’t used for Nefettiti’s burial or were taken out of that burial to be reused for Tut. Both possibilities are a bad sign for Nefertiti. To be denied a royal burial or have it pillaged was a tremendous insult and was tantamount to being erased from history.

Therefore, did Nefertiti do something that caused her burial to be denied or desecrated? Her links with the hated Atenist revolution and Akhenaten himself could have exposed her to backlash. The immediate conservative pivot of Tut’s reign also hints at some sort of visceral reaction to the Atenist project. Was she a victim of anti-Atenist persecution? Was her reign one of unrest and resentment from a populace that hated her solar religion? Even if she did roll back those reforms, it might have been too little too late. When she died – however she died — it seems she had not earned much respect from those who laid her to rest.

Forgetting Nefertiti

Nefertiti and the entire Amarna period were erased from history by later Pharaohs who wanted to expunge the blot of the heretical Atenist experiment from the records. Every name, every inscription, every painting referencing Nefertiti was destroyed or dismantled, condemning her to oblivion for millennia.

Nefertiti was lost to history for three thousand years until excavations at Amarna rediscovered her in the late 19th century. Unorthodox as her life may have been, even the archaeologists re-discovering her probably only expected Nefertiti to become another one of thousands of names known to Egyptology — pulled from the abyss of history but then condemned to scholarly tomes and the curiosity of Egyptophiles forever more, but thanks to a single discovery, that was not going to happen.

The Iconic Nefertiti Bust

On 6th December 1912, excavators in Amarna were uncovering a sculptor’s workshop when they found something remarkable. Buried upside down in the sand was an unprecedented example of ancient Egyptian portraiture. A bust, still brightly painted, depicting Queen Nefertiti in her prime.

The Nefertiti Bust is one of the most iconic images of Egyptology and has made her an eminently recognizable figure well beyond Egyptology. Nefertiti’s name and image are a byword for beauty and feminine power, inspiring novels, artwork, fashion, music, and more. The later discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb and the continual fascination with Akhenaten and the Atenist phenomenon over the past century have only raised her profile.

The Nefertiti Bust now sits in the Neues Museum in Berlin, where its presence continues to cause friction between Egypt and Germany. Adolf Hitler was once advised to return the bust to Egypt as a sign of goodwill and to secure a potential alliance against the British. The dictator refused, stating plainly that, “I will never relinquish the head of the Queen.”

Nefertiti’s secrets still grab headlines. Scholar Nicholas Reeves has gained much attention in recent years with claims that Neferiti’s tomb lies in a secret chamber behind the walls of King Tut’s resting place. Other scholars like Dr Zahi Hawass have continued their own searches for the tomb of Egypt’s most recognizable Queen.

From Akhenaten to Hitler, from the workshop of Thutmose to the museums of Berlin, Nefertiti has an indefatigable power to fascinate and inspire. Half a million people go to visit her bust every year, and many more gander at the Amarna artifacts strewn about in museums across the globe. But beyond the famous art lies a remarkable woman, a revolutionary, a visionary, a ruler, a mother, and a mystery that continues to enthrall people. ‘The Beautiful One Has Come’ indeed, and she is not going anywhere any time soon.