The Taş Tepeler, or Stone Mounds, in southeastern Turkey’s Şanlıurfa Province arc roughly 125 miles along the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, overlooking the Harran Plain and the Balikh River, a tributary of the Euphrates. The region features plateaus amid modest mountains. Scorching summers and mild winters with little rain barely sustain wild lentils, wheat, barley, and chickpeas, alongside other plant species adapted to the semiarid steppe environment. Farmers cultivate crops of pistachios, which are known locally as “green gold.” The plain’s few native animals, including several species of gazelle, are legally protected, but conservationists struggle to safeguard them from poaching, climate change, and urban expansion. In villages dotted across the plain, residents face challenges, too, their lives intertwined with seasonal agricultural rhythms and subject to the vagaries of swiftly changing weather patterns.

The Taş Tepeler, or Stone Mounds, in southeastern Turkey’s Şanlıurfa Province arc roughly 125 miles along the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, overlooking the Harran Plain and the Balikh River, a tributary of the Euphrates. The region features plateaus amid modest mountains. Scorching summers and mild winters with little rain barely sustain wild lentils, wheat, barley, and chickpeas, alongside other plant species adapted to the semiarid steppe environment. Farmers cultivate crops of pistachios, which are known locally as “green gold.” The plain’s few native animals, including several species of gazelle, are legally protected, but conservationists struggle to safeguard them from poaching, climate change, and urban expansion. In villages dotted across the plain, residents face challenges, too, their lives intertwined with seasonal agricultural rhythms and subject to the vagaries of swiftly changing weather patterns.

More than 11,000 years ago, during the early Neolithic period, this was a lush expanse of mighty forests teeming with wild animals including cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys, gazelles, boars, leopards, and snakes and other reptiles. Its rivers and lakes were home to numerous species of fish and birds. This fertile environment drew groups of mobile hunter-gatherers who, freed from the need to move seasonally in search of food, built semipermanent and permanent dwellings on the plain and in the hills. “This part of Anatolia had a significantly richer and more productive natural environment than arid regions to the south,” says archaeologist Mehmet Özdoğan of Istanbul University. “This encouraged people to establish permanent settlements and liberated them from mere dietary concerns. Their newfound freedom allowed them to focus on endeavors beyond sustenance and shelter and on what we might define as true artistic pursuits.”

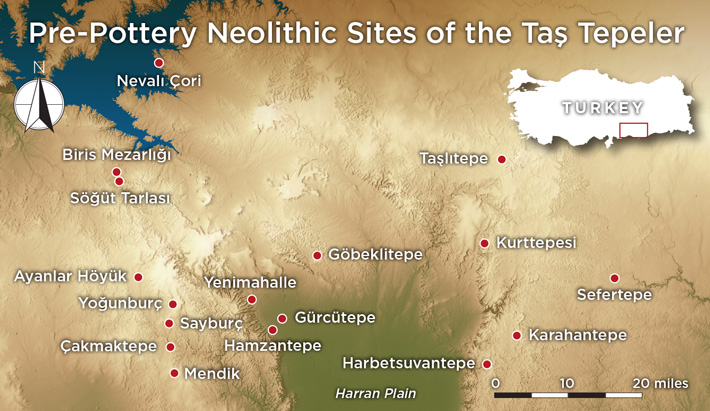

Archaeologists working across the region over the last several decades have uncovered more than 20 sites dating to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period (ca. 12,000 to 10,200 years ago). These sites share characteristics such as monumental architecture, often in the form of T-shaped or rounded pillars and large decorated stone benches. They also feature stone carvings of humans with skeletal features, as well as of human heads, masks, phalluses, and predatory mammals, including raptors and snakes. Between 1983 and 1991, at the site of Nevalı Çori, which is now covered by the waters of the Atatürk Reservoir, researchers discovered a series of large T-shaped standing stones that are acknowledged to be the first known examples of monumental architecture in the region. Inspired by those finds, later in the 1990s, archaeologists returned to the site of Göbeklitepe, some 35 miles away, which had been discovered in 1963. There they unearthed structures similar to those at Nevalı Çori. (See “Last Stand of the Hunter-Gatherers?”) While digging at Sayburç, another of the Taş Tepeler sites, in 2021, archaeologist Eylem Özdoğan of Istanbul University unearthed a stone bench with a carved relief showing two humans, two leopards, and a bull—a scene, she says, that represents the most detailed depiction of a Neolithic story found to date.

Archaeologists working across the region over the last several decades have uncovered more than 20 sites dating to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period (ca. 12,000 to 10,200 years ago). These sites share characteristics such as monumental architecture, often in the form of T-shaped or rounded pillars and large decorated stone benches. They also feature stone carvings of humans with skeletal features, as well as of human heads, masks, phalluses, and predatory mammals, including raptors and snakes. Between 1983 and 1991, at the site of Nevalı Çori, which is now covered by the waters of the Atatürk Reservoir, researchers discovered a series of large T-shaped standing stones that are acknowledged to be the first known examples of monumental architecture in the region. Inspired by those finds, later in the 1990s, archaeologists returned to the site of Göbeklitepe, some 35 miles away, which had been discovered in 1963. There they unearthed structures similar to those at Nevalı Çori. (See “Last Stand of the Hunter-Gatherers?”) While digging at Sayburç, another of the Taş Tepeler sites, in 2021, archaeologist Eylem Özdoğan of Istanbul University unearthed a stone bench with a carved relief showing two humans, two leopards, and a bull—a scene, she says, that represents the most detailed depiction of a Neolithic story found to date.

Taken together, the known Taş Tepeler sites—and perhaps others yet to be discovered—suggest something revolutionary was happening in the area at this time. “These excavations have altered people’s perspectives on the Neolithic period,” says archaeologist Douglas Baird of the University of Liverpool, who is now working at Mendik, a newly discovered Taş Tepeler site. “We know that many Neolithic areas, from Jordan to Cappadocia in Anatolia, have public buildings, but in the Taş Tepeler region, there are numerous structures designated for specific public or ritual purposes. I believe the most important aspect of public buildings is that they represent new social institutions in these communities—for which other evidence is lacking—because they brought together different families and different segments of the community for a common purpose.” These large gathering spaces underscore the significance of such communal activities. During this period, buildings became something other than just spaces to live in, and “special structures” began to be built for non-domestic purposes, an indicator of new spiritual practices. “Considering the labor and time required for the construction of these structures, they must have held great meaning for Neolithic societies,” Baird says. “The goal shouldn’t be to understand one settlement, but to understand the entire region and the story that is specific to this region. When you look at the plateau surrounding the Harran Plain, you find a lot of these types of sites, but as you go a bit farther, they disappear. This region has a unique coherence.”

Taken together, the known Taş Tepeler sites—and perhaps others yet to be discovered—suggest something revolutionary was happening in the area at this time. “These excavations have altered people’s perspectives on the Neolithic period,” says archaeologist Douglas Baird of the University of Liverpool, who is now working at Mendik, a newly discovered Taş Tepeler site. “We know that many Neolithic areas, from Jordan to Cappadocia in Anatolia, have public buildings, but in the Taş Tepeler region, there are numerous structures designated for specific public or ritual purposes. I believe the most important aspect of public buildings is that they represent new social institutions in these communities—for which other evidence is lacking—because they brought together different families and different segments of the community for a common purpose.” These large gathering spaces underscore the significance of such communal activities. During this period, buildings became something other than just spaces to live in, and “special structures” began to be built for non-domestic purposes, an indicator of new spiritual practices. “Considering the labor and time required for the construction of these structures, they must have held great meaning for Neolithic societies,” Baird says. “The goal shouldn’t be to understand one settlement, but to understand the entire region and the story that is specific to this region. When you look at the plateau surrounding the Harran Plain, you find a lot of these types of sites, but as you go a bit farther, they disappear. This region has a unique coherence.”

A compelling narrative of Neolithic existence has begun to emerge. “These sites reveal a transformation that took place over 1,500 years beginning about 11,500 years ago, when the region’s peoples made advancements in domesticating animals and agriculture as a result of the ability to create permanent settlements. This signifies a profound evolution as an agrarian lifestyle took hold,” says archaeologist Necmi Karul of Istanbul University. “In the early stages of the Neolithic era, while people continued the hunter-gatherer way of life, a new type of social order was being constructed.” These people were presented with the kinds of challenges that come about when large groups live together. “Among these challenges,” says Karul, “we see the construction of spaces that bring people together, an iconographic narrative that could be considered a product of shared memory, and especially the production of objects with high artistic qualities.”

A compelling narrative of Neolithic existence has begun to emerge. “These sites reveal a transformation that took place over 1,500 years beginning about 11,500 years ago, when the region’s peoples made advancements in domesticating animals and agriculture as a result of the ability to create permanent settlements. This signifies a profound evolution as an agrarian lifestyle took hold,” says archaeologist Necmi Karul of Istanbul University. “In the early stages of the Neolithic era, while people continued the hunter-gatherer way of life, a new type of social order was being constructed.” These people were presented with the kinds of challenges that come about when large groups live together. “Among these challenges,” says Karul, “we see the construction of spaces that bring people together, an iconographic narrative that could be considered a product of shared memory, and especially the production of objects with high artistic qualities.”

About 30 miles southeast of Göbeklitepe, the recently discovered site of Karahantepe sits atop a rocky outcrop 2,600 feet above sea level and covers some 25 acres. Since 2019, a team led by Karul has excavated more than half an acre of the site and unearthed a stunning array of structures and sculptures characteristic of Taş Tepeler sites. Surface surveys have shown that Karahantepe is divided into four distinct sectors: one each on the east and west terraces of the slope, where many of the special structures are located; the site’s quarries; and the southern plain, where archaeologists have found grinding stones, flints, and other objects of daily life suggesting that this may have been a domestic area.

About 30 miles southeast of Göbeklitepe, the recently discovered site of Karahantepe sits atop a rocky outcrop 2,600 feet above sea level and covers some 25 acres. Since 2019, a team led by Karul has excavated more than half an acre of the site and unearthed a stunning array of structures and sculptures characteristic of Taş Tepeler sites. Surface surveys have shown that Karahantepe is divided into four distinct sectors: one each on the east and west terraces of the slope, where many of the special structures are located; the site’s quarries; and the southern plain, where archaeologists have found grinding stones, flints, and other objects of daily life suggesting that this may have been a domestic area.

Over time, farming became the region’s dominant way of life. At least at the start, however, the area’s inhabitants remained hunters as well. Archaeologists have found that Taş Tepeler sites are often surrounded by hunting grounds marked with stones arranged in specific configurations. To date, nearly 300 of these trapping areas have been identified, a testament to a thriving hunting environment. At Karahantepe, for example, archaeologists have found hunting grounds that the site’s inhabitants demarcated by stacking stones to a height of about two feet in a pattern that resembles fish scales when viewed from above to enclose a V-shaped space where deer were cornered and killed. “It’s clear that novel hunting techniques were developed at this time,” Karul says. “This enabled a more advanced and expansive type of control over larger herds of animals.

Over time, farming became the region’s dominant way of life. At least at the start, however, the area’s inhabitants remained hunters as well. Archaeologists have found that Taş Tepeler sites are often surrounded by hunting grounds marked with stones arranged in specific configurations. To date, nearly 300 of these trapping areas have been identified, a testament to a thriving hunting environment. At Karahantepe, for example, archaeologists have found hunting grounds that the site’s inhabitants demarcated by stacking stones to a height of about two feet in a pattern that resembles fish scales when viewed from above to enclose a V-shaped space where deer were cornered and killed. “It’s clear that novel hunting techniques were developed at this time,” Karul says. “This enabled a more advanced and expansive type of control over larger herds of animals.

Although excavations at Karahantepe are at a very early stage, the team has already unearthed four special structures, which Karul has named AA, AB, AC, and AD. “The plans of these structures are distinct from each other, and they were designed and constructed simultaneously, indicating that each had a separate purpose,” says Karul. “They were likely constructed with communal consent and served functions relevant to the general community.” For example, structure AD, with its central location, ample dimensions, seating arrangements suitable for a large group, and recurring iconographic elements that are found in contemporaneous Taş Tepeler settlements, appears to have been a gathering place for crowds

Structure AB is a type of building that, says Karul, has never been encountered before. The oval space covers 450 square feet. It was carved into the bedrock and contains 10 phallic pillars, each about six feet high. Poking out from one of the walls is a carving of a menacing human head, possibly with a serpent’s body, which, Karul says, is a symbol of male power. There are, he notes, very few representations of or objects related to women from this period. “This scarcity, almost to the point of absence, can be explained by the possibility that objects related to women have not survived to the present day,” Karul says. “The use of hard materials like stone for masculine symbolic elements may suggest a deliberate choice.”

Structure AB is a type of building that, says Karul, has never been encountered before. The oval space covers 450 square feet. It was carved into the bedrock and contains 10 phallic pillars, each about six feet high. Poking out from one of the walls is a carving of a menacing human head, possibly with a serpent’s body, which, Karul says, is a symbol of male power. There are, he notes, very few representations of or objects related to women from this period. “This scarcity, almost to the point of absence, can be explained by the possibility that objects related to women have not survived to the present day,” Karul says. “The use of hard materials like stone for masculine symbolic elements may suggest a deliberate choice.”

Structure AB also has a channel and stairs that Karul says could be related to a water ritual. Some have been tempted to call the special structures at Karahantepe, and similar examples at other Taş Tepeler sites, temples. But for Karul this is premature at best. “It’s difficult to call these structures temples until we know what took place inside them,” he says. “Did people gather and celebrate, or did a council tasked to solve problems meet there? Or was the building multifunctional, covering all these possibilities? We just don’t know.”

Among the many unknowns of the sites of the Taş Tepeler, there is perhaps none greater than why Neolithic builders expended so much care and effort on these structures only to bury them. The question of why Neolithic people intentionally buried both residential and public buildings has been an enduring topic of debate since the 1960s, when many examples of this phenomenon were first identified in Anatolia and across the Near East. “One of the indicators that a structure has significance beyond being just a space for specific activities, and that it can have a higher meaning, is that people deliberately buried it after it completed its intended function,” says Mehmet Özdoğan. This is especially true of the special structures of the Taş Tepeler.

At Karahantepe, the stones and artifacts filling the special structures were placed there and were not the result of erosion. In structure AB, Karul’s team identified brown and red sterile soil—soil that doesn’t contain any archaeological materials—some 10 to 12 inches thick at the bottom. “During the filling process, people generally used soil from the closest area, so there should have been a mixture of archaeological materials, stones, etcetera,” Karul says. “Yet at the very bottom of the structure, we found sterile soil that was brought from somewhere else and laid there, and then the material collected from the surroundings was deposited on top.” The team also observed that stones of different sizes had been placed atop the large phallus-shaped pillars to even out the surface. Karul believes that people closed the structure in stages, first moving the sterile soil and later placing the stones.

At Karahantepe, the stones and artifacts filling the special structures were placed there and were not the result of erosion. In structure AB, Karul’s team identified brown and red sterile soil—soil that doesn’t contain any archaeological materials—some 10 to 12 inches thick at the bottom. “During the filling process, people generally used soil from the closest area, so there should have been a mixture of archaeological materials, stones, etcetera,” Karul says. “Yet at the very bottom of the structure, we found sterile soil that was brought from somewhere else and laid there, and then the material collected from the surroundings was deposited on top.” The team also observed that stones of different sizes had been placed atop the large phallus-shaped pillars to even out the surface. Karul believes that people closed the structure in stages, first moving the sterile soil and later placing the stones.

The objects unearthed in the special structures provide further evidence of ritual burying. “Thus far, we have found artifacts in AC and AD that have been partially damaged and, along with layers of stone, systematically buried one on top of the other,” Karul says. Structure AD features two opposing areas on the north and south sides where objects were intentionally left or discarded. Some of the objects had been broken and thrown into the structure from above so they would face downward. In certain instances, sculptures, including those of human heads, were placed facing the wall or the ground. “This might be considered coincidental,” says Karul, “but its repetition suggests a deliberate action.”

The objects unearthed in the special structures provide further evidence of ritual burying. “Thus far, we have found artifacts in AC and AD that have been partially damaged and, along with layers of stone, systematically buried one on top of the other,” Karul says. Structure AD features two opposing areas on the north and south sides where objects were intentionally left or discarded. Some of the objects had been broken and thrown into the structure from above so they would face downward. In certain instances, sculptures, including those of human heads, were placed facing the wall or the ground. “This might be considered coincidental,” says Karul, “but its repetition suggests a deliberate action.”

The entrance and exit at opposite ends of structure AB suggest people followed a ritual process that involved traveling through the space in a specific direction. “It’s possible that structures like AB may have been linked to initiation ceremonies,” Karul says. “Such rites of passage are considered crucial milestones in forming social cohesion.” The team has also found that nearly all the sculptures depicting humans have damage to their noses, and some have damage to their mouths as well. “The deliberate damage to the sculptures suggests that this was part of a termination process,” says Karul.

The entrance and exit at opposite ends of structure AB suggest people followed a ritual process that involved traveling through the space in a specific direction. “It’s possible that structures like AB may have been linked to initiation ceremonies,” Karul says. “Such rites of passage are considered crucial milestones in forming social cohesion.” The team has also found that nearly all the sculptures depicting humans have damage to their noses, and some have damage to their mouths as well. “The deliberate damage to the sculptures suggests that this was part of a termination process,” says Karul.

At both Göbeklitepe and Karahantepe, although settlements continued to be built around special structures after they had been filled in, Neolithic people didn’t build on the specific places where buildings belonging to their ancestors once stood. Karul suggests that burying these structures also symbolically buried the experiences that took place within them, preserving their references to the past. “It’s possible they believed they could find the place again when they returned,” he says, “or that they wanted to conceal certain things.”

Baird, too, interprets the intentional burial of buildings as a form of sealing. He points to his work at Boncuklu Höyük, a Neolithic site that was one of the oldest permanent settlements in Central Anatolia, where he has directed excavations since 2006. There, Baird has also found examples of buried houses. Deceased individuals were often interred within these homes, and later, when the life span of a house had ended, it was also buried. Baird believes that a similar practice might have been carried out in the special structures of Taş Tepeler sites, and that the region’s Neolithic people were deeply committed to undertaking the process collectively. This cycle, he says, reflects an element of settled life. Particularly in the case of large construction projects, it signifies a profound dedication to the prolonged, shared use of a specific location people chose for the opportunities it provided.

Baird, too, interprets the intentional burial of buildings as a form of sealing. He points to his work at Boncuklu Höyük, a Neolithic site that was one of the oldest permanent settlements in Central Anatolia, where he has directed excavations since 2006. There, Baird has also found examples of buried houses. Deceased individuals were often interred within these homes, and later, when the life span of a house had ended, it was also buried. Baird believes that a similar practice might have been carried out in the special structures of Taş Tepeler sites, and that the region’s Neolithic people were deeply committed to undertaking the process collectively. This cycle, he says, reflects an element of settled life. Particularly in the case of large construction projects, it signifies a profound dedication to the prolonged, shared use of a specific location people chose for the opportunities it provided.

Over the past 25 years, scholars’ understanding of the Neolithic period has changed radically, largely because of the discoveries in the Taş Tepeler. Where farming was once thought to have spurred permanent settlement, it is now well accepted that hunter-gatherers were living in at least semipermanent settlements long before agriculture became the dominant way of life. These people were also building monumental structures that archaeologists believe are evidence of changing social norms, rituals, and institutions. “Before these new discoveries, the only site we could compare the data from Göbeklitepe to was Nevalı Çori,” says archaeologist Lee Clare of the German Archaeological Institute. With the excavation of another large area such as Karahantepe, archaeologists can test their hypotheses about buildings being filled in and symbolism at multiple sites. “The most beautiful aspect of the Taş Tepeler is that we have a region that was occupied from the early Neolithic to the late Neolithic period,” Clare says. “This makes it one of the best research areas for the entire Neolithic era.”

For Karul, the sites of the Taş Tepeler reveal a society that was highly organized beginning around 12,000 years ago, followed by a period of fundamental change during which people displayed tremendous creativity. “The architecture in the construction of monumental structures, the deliberately planned settlement patterns, and the intricately crafted human and animal sculptures exemplify this sophistication,” he says. “While people spent millions of years in nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles consuming resources from their surroundings, in a relatively short period of time, their transition to settled life brought about one of the significant transformations in human history.”

Tolga Ildun is a photojournalist living in Istanbul