Updated April 2024: The garden has become an essential sanctuary in our lives. Even years after the COVID-19 pandemic peak, nature’s solace remains a powerful draw, providing both inspiration and guidance. For this 2021 essay, we delved into the significant impact gardens have on our mental and physical well-being, speaking with authors, landscape leaders, and philanthropists from around the world.

Many of these visionaries continue to affect change globally, including Tom Stuart-Smith and Sue Stuart-Smith, who will be showcasing their expertise at the Royal Horticultural Society’s 2024 Chelsea Flower Show. Today, their insights on the vital role gardens ought to play in our daily lives are as relevant as ever.

It began, as many gardens do, with vegetables cultivated outside the back door. But it grew into a sanctuary that was as vital as oxygen to Anne Spencer, poet of the Harlem Renaissance and citizen of Lynchburg, Virginia. With the loving enterprise of her husband, Edward, the celebrated Black poet cultivated a verdant haven for work, retreat, and welcoming friends in a racially punishing Southern city.

“It became a place where she could escape,” says Shaun Spencer-Hester, granddaughter of the poet and guardian of her legacy at what is now the Anne Spencer House & Garden Museum. “I do go there to rake leaves and things like that, but really I go because it’s such a peaceful place,” she says. “I think about my grandmother doing this same thing. A peaceful place where she could think about cultivating plants and about the challenges that she as a woman, and she as a Black woman, faced, and to maybe work that out in her head, like writing a poem.” Spencer-Hester describes the brightly painted writer’s cottage her grandfather built, the birds tended to by her grandparents that also found refuge in their embrace, the coterie of Black writers from New York returning to luxuriate in the perfumed shade of their Southern childhoods. Most of all, she summons her grandmother, who fought for a seat on a segregated trolley, who pressed for a job as a librarian in front of an all-white board, and who published poems of nature that spoke directly to racial injustice. When asked if she feels like the garden can save us all, Spencer-Hester answers without a speck of hesitation. “It saved Anne Spencer,” she says.

At this moment in our collective history, that question has never seemed more pressing. Or with an answer more obvious. The garden—a human invention that meets nature at her threshold—provides sustenance of literal, aesthetic, spiritual, and even metaphorical value. We have tended plots from far back in prehistory, discovering the benefit of growing amid the earliest survival schema of foraging and hunting. We discovered further, over millennia, the gifts borne by plants—from nutrients and succor to medicines and alterations of mood—and we expended energy to put those plants close by and help them grow. We gardened.

But over time, inhibitors (big agriculture, overbuilding, a culture that rewards the fast and electronic) invaded the Edenic space. Perhaps even, too many of us took ourselves out of the garden. And yet, when nature’s own hand challenged us with a life-threatening virus, we pushed open doors and took deep, healthy breaths outside. We remembered, like waking from a dream, that in our gardens we thrive. Now, as seasons turn over and science flexes a molecular antidote to a global pandemic, have we not re-glimpsed the greater power of one’s own—and every garden—to save us all? Have we not been reminded that our salvation is embedded in the hopeful act of planting seeds each spring? The careful tending of new shoots, the active dance with weather and fauna, and the joyful gifts of blooms and bounty?

The answer, Sue Stuart-Smith posits, is right there in the soil.

To say that Stuart-Smith understands what the garden does for us barely captures the depth and breadth of her stunning 2020 book, The Well-Gardened Mind: The Restorative Power of Nature. Drawing on her experience creating and tending her family’s noteworthy Hertfordshire garden in England with husband and famed garden designer Tom Stuart-Smith and inspired by her grandfather’s lifesaving turn to nature as a salve for physical and existential wounds from WWI, the psychiatrist and psychotherapist has explored the extraordinary effects of working in and inhabiting gardens.

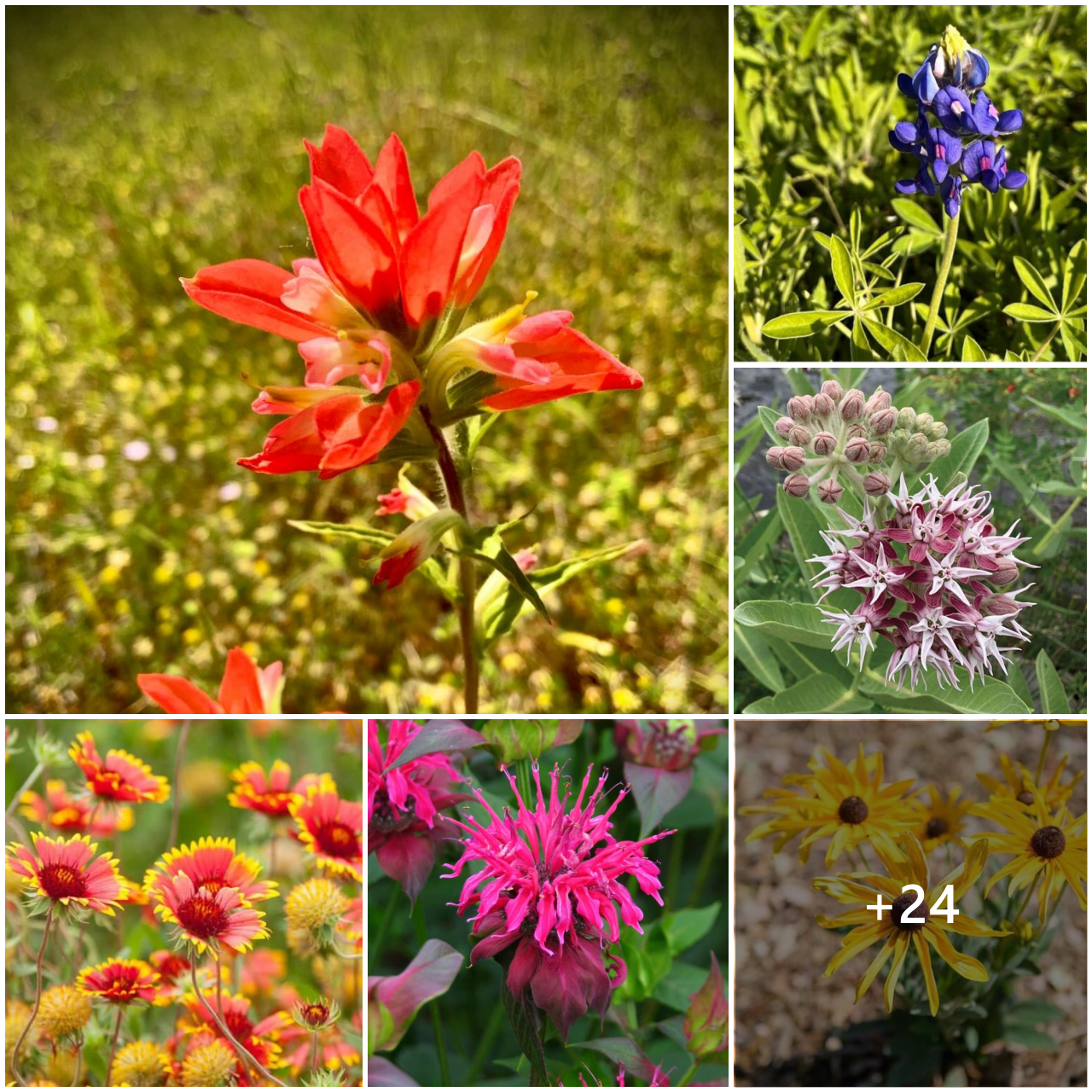

Indeed, Stuart-Smith’s stirring summaries of the garden’s history, value in therapeutic settings, and place in literature and culture feel like the best kind of circumstantial evidence for the primacy of the act. But when she digs into the emerging neuroscience, the evidence is breathtaking. Take, for example, what actually lives in the soil. Bacterial actinomycetes, when activated by water, emit an aroma called geosmin that has a pleasing and soothing effect on most people, Stuart-Smith points out. Heart rate and blood pressure drop within minutes of exposure to natural surroundings like parks and gardens. Cortisol—the fight-or-flight hormone that assaults our well-being when we endure sustained stress—drops within 20 to 30 minutes. The scents of blooms from lavender, rosemary, and citrus summon mood-elevating chemicals. The scent of roses actually allows our body to hang onto endorphin highs longer, extending that blissful inhalation.

But the roots of the garden reach deeper into our psyches. For Connecticut-based landscape architect Janice Parker, exposure to the vagaries of nature paradoxically liberates her—a feeling she labels as joy. “With a garden, whatever can go wrong, will go wrong,” she says. “It’s a constant experiment, because nature is constantly changing. If you can find yourself accepting that variability, you can study change and get comfortable with it, and that opens the door to feeling a lot more joy in your life.”

Parker admits to loving the assurance of a plan but laughs at how it can all be undone in an instant. “When we accept that Mother Nature rules, we become happier,” she offers. “If you think you can control it, but you can’t, there’s no joy there. There’s always tension and misery. If you look up at the dappled sky through a tree and realize that the five trees that fell down on the property had nothing to do with you, you experience the grace of that moment.” The metaphysics of humility is a theme to which every gardener will attest. As humbling as it is to witness one’s best laid plans unmade, there is the twinned promise and evidence of success with every planted seed that sprouts. Along the way, the act of nurturing infuses the gardener with deep and lasting satisfactions reinforced by—again—neurochemistry in the form of soothing baths of oxytocin and endorphins. It feels good to care.

“A garden is always the expression of someone’s mind and the outcome of someone’s care,” Stuart-Smith writes. “When we step back from it, how can we tease apart what nature has provided and what we have contributed?…Sometimes when I am fully absorbed in a garden task, a feeling arises within me that I am part of this and it is part of me; nature is running in me and through me.”

For New York–based landscape designer Wambui Ippolito, nature can confer almost coded messages, particularly in private gardens. Having grown up playing in the lush surroundings of her grandparents’ farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley, Ippolito articulates the power of plants to maintain one’s sense of heritage and place. “Africans came from a place where land was everything: life, healing, communicating with the gods,” she says. “And then they were thrust here and couldn’t have that relationship anymore. Their relationship [through enslavement] became forced, brutal, traumatic.

“It’s a complete and utter loss of family history, ancestral history,” she says, adding that immigrants also lost many connections through assimilation. But a garden can restore those ties. “You have to connect those dots back,” she says. Ippolito works with her clients to reach back into their family trees for clues to plants that restore a loop across time and oceans. And when she does, her clients express a new connection to their gardens they’ve never had before. “They’re proud to tell their friends the story of that rose from their Belarus ancestors, or that plant that grows in the Middle Eastern landscape,” she says. “I hope in my work that I’m allowing people to see that they’re coming from a huge history of a benevolent way of interacting with nature and each other.”

The nourishment of the garden is central to Ron Finley, whose pioneering work in South Central Los Angeles puts the right of every individual to grow their own food at its very heart. The “Gangster Gardener,” artist, and designer became horticulturally radicalized over a fight with the city. The problem? He wanted to plant the parkway, a barren strip running past his house, with food and flowers. “It was sensory,” he says. “I wanted to walk out of my place and not see someone’s trash on the parkway. I wanted to walk out and smell and see beauty. I wanted to walk out and have hummingbirds land on my shoulder, butterflies on my head. You see these things in other neighborhoods. Why can’t this one have that?”

Finley did what any gardener does. He tilled and tended, and soon his strip yielded a lush patch of beauty with spindles of sunflowers so tall they stopped jaded teens rolling by to ask Finley if those things were actually real. The city told him he had no right to do it on their land, and Finley dug in, ultimately achieving a change to the law to allow it. Now, Finley’s entire property is an urban sanctuary complete with a waterless Olympic-size swimming pool painted with vibrant murals that holds an exuberance of plants in pails, buckets, and boxes: a sunken garden for the 21st century. “Gardens represent freedom,” Finley says. “That’s one of the reasons I started growing food myself.” And he wants his community to gather around growing food as a form of revolution against the injustice of urban food deserts and the power-sapping influence of technology. “It’s another form of slavery,” he says. “You depend on someone to do everything for you. You got your phone, you press a button, and you don’t know how to read a map. We need to get back to experiences that have value.”

Another rebellious gardener, Bette Midler, returned to New York in 1995 and was appalled at the literal trashing of the city where she’d launched her career 30 years prior. Much like Finley, she took matters into her own (gloved) hands and began picking up litter in two parks in Upper Manhattan. Midler’s grassroots effort blossomed that year into the New York Restoration Project (NYRP), a nonprofit conservancy that now works with local communities, public agencies, and the private sector to give nature back to New Yorkers in all five boroughs.

The bounty of NYRP is varied and abundant. In 2007, following a design by Janice Parker, they planted hundreds of blossoming cherry trees along the Harlem River Greenway. This inspired then-mayor Michael Bloomberg to think big—really big—and launch an initiative with NYRP to plant one million new trees in the city (the millionth tree was planted in Joyce Kilmer Park in the Bronx in 2015). NYRP owns and supports 52 community gardens citywide and maintains 80 acres of parks in Upper Manhattan—including Sherman Creek Park, a former illegal dumping ground on the Harlem River that has blossomed with a teaching garden and oyster-fueled living shoreline. And it works nimbly with communities—particularly those historically marginalized—on cultivating green and safe spaces where locals want them.

Janice Parker recalls luring well-known U.K. horticulture writer and broadcaster Monty Don to visit a NYRP community garden in the Bronx. Parker recounts the scene, which moved Don to tears: “There was a group having a yoga class, an older group of fellows setting up for a jazz concert. Some members of the LGBTQ community were doing some cleanup. Kids were getting a reading lesson. Someone was harvesting from a peach tree. None of it was staged,” she says. “It was just a Saturday.”

Saturday in the garden. Restoration. Splendor. Sustenance. Delight. No matter the scale, the planting zone, or the budget for shoots and seeds, the language of the garden crosses every border. From the conceits of monarchs and millionaires to the tidy plot out a gardener’s back door, the essential good of the garden abides.

And like a pebble tossed in a garden’s small, still pond, that good flows from the cultivator’s hand: over hedges into the swirling world of the pollinator and the bird, borne on the backs of small creatures, into the web of beauty and of life that supports us all. The seasonal sowing of hope by every gardener becomes our shared hope for salvation. Can the garden save us all? It’s been doing so all along, as Anne Spencer’s sanctuary, lovingly preserved by her granddaughter, reminds us. Whether we tend arduously, putter meditatively, or merely find a bench to rest and gaze, we are all the most fortunate of gardeners, looking forward to planting season.