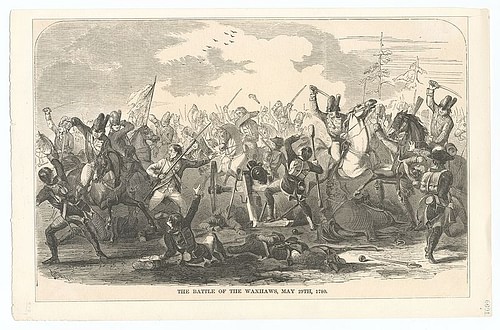

The Battle of Waxhaws (29 May 1780) was a small engagement during the southern theater of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) that nevertheless had a significant psychological impact on the Patriots. During the battle, Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton and his infamous British Legion allegedly slaughtered Patriot soldiers who were trying to surrender, increasing the perception of British soldiers as ruthless.

Charleston Under Attack

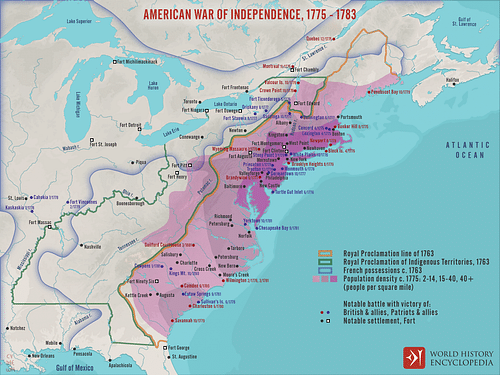

In March 1780, the chaos and destruction of the Revolutionary War came to South Carolina. Over 10,000 British and German soldiers, under the command of Sir Henry Clinton, had landed at Drayton’s Landing, 12 miles (19 km) to the north of the city of Charleston. On 29 March, the army crossed the Ashley River and dug in outside the city’s landward defenses, beginning to lay siege. Meanwhile, Royal Navy vessels had entered Charleston Harbor, having slipped past the sandbar that was supposed to prevent such a movement; the panicked American commodore in charge of the city’s naval defenses decided to scuttle his eight ships rather than face the firepower of Royal Navy warships. In the ensuing weeks, the British siegeworks inched closer to the walls of Charleston, undeterred by the incessant fire of the American artillery. It was only a matter of time, it seemed, before the Union Jack flew above the walls of Charleston.

If Charleston were to fall, the British could control the trade flowing out of the American South, thereby crippling the US economy.

Major General Benjamin Lincoln, in charge of the American army within the city, was aware of the direness of his situation. Charleston was, at the time, the jewel of the American South. It was not only the largest city in the South but also the economic center of the region; indigo and rice, two of the most profitable crops grown on South Carolinian plantations, were exported from Charleston docks, the sale of which was used to help fund the United States’ war effort. If the city were to fall, the British would not only gain an important foothold in South Carolina but could also more easily control the trade flowing out of the American South, thereby crippling the US economy. Civilian officials begged General Lincoln not to surrender the city, no matter the cost to his army. Lincoln did his best to comply but knew his situation was growing bleaker every day. On 14 April, his route of retreat across the nearby Cooper River was cut when a detachment of British dragoons, led by Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton, surprised and defeated the American outpost at Monck’s Tavern. Hours later, the energetic Tarleton had captured all major crossing points over the Cooper within 6 miles (10 km) of Charleston. Now, Lincoln’s army was well and truly trapped.

Though growing dimmer by the day, Lincoln’s situation was not entirely hopeless. General George Washington, commander-in-chief of the American forces, was busy leading the main army in New Jersey and could not come to Lincoln’s aid himself; Washington did, however, send two Continental regiments under the Bavarian-born General Johann de Kalb to aid in Charleston’s defense. At the same time, Colonel Abraham Buford and the 380 soldiers of the 3rd Virginia Regiment had marched down from Virginia to help protect the Carolinas from the British. By 5 May, Buford’s men arrived at Lenud’s Ferry, on the northern side of the Santee River, 40 miles (64 km) from Charleston. Here, the Virginians encountered a small party of American troops under Colonel Anthony Walton White and Colonel William Washington (a second cousin of the general). White and Washington had gathered the survivors of Tarleton’s raids along the Cooper River and regrouped at Lenud’s Ferry.

Battle of Lenud’s Ferry

Once Buford explained that he was trying to reach Charleston, White and Washington decided to help. On 6 May, White led a small company of Virginia dragoons across the river, to see if the coast was clear for Buford to make a dash for Charleston. Initially, White’s reconnaissance mission went well; a British officer and 17 light infantrymen were taken prisoner while foraging for food on a deserted plantation. Satisfied, White and his dragoons then began to ride back to Lenud’s Ferry to rendezvous with Buford – they would never make it. As White’s men were attempting to cross back over the river, they were attacked by Tarleton and 150 British dragoons. The attack took the Americans completely by surprise; 36 Americans were killed or wounded, with 60 others becoming prisoners. Several Americans, including White and Washington, escaped by jumping into the Santee and swimming across; although White and Washington made it to the other side, a few others drowned in the attempt.

With Tarleton’s horses prowling the southern side of the Santee, Buford was unable to march to Charleston’s aid. Even if he had been able to, he was much too late to make a difference. By this point, the British siegeworks had reached the walls of Charleston, while heavy bombardments from British artillery had set the city’s wooden buildings ablaze. On 12 May 1780, General Lincoln finally surrendered both the city and his entire army. The British reported the capture of 5,466 Continental officers and men, 5,316 muskets, 15 regimental colors, and about 33,000 rounds of small arms ammunition. It was arguably the worst American defeat of the war, as well as the largest American army to surrender to an enemy force prior to the Battle of Harper’s Ferry in 1862.

Pursuit

The end of the Siege of Charleston and the surrender of Lincoln’s army left Buford’s tiny force as the only part of the Continental Army to remain in South Carolina. De Kalb’s detachment had made it to North Carolina when it learned of Charleston’s fall; rather than press on, de Kalb decided to remain at Greensboro as he awaited fresh orders (for the fate of de Kalb and his men, see the article on the Battle of Camden). Buford, having suddenly found himself isolated in what was now enemy territory, decided that his best course of action was to retreat into North Carolina and perhaps link up with de Kalb’s force. But as the column of Virginians began to head back north, it found itself pursued by a force that was already accumulating a fearsome reputation: the British Legion commanded by the young and ruthless Banastre Tarleton.

Tarleton was the son of a prosperous Liverpool family; his father was a merchant who had gotten rich off the West Indian sugar trade and the slave trade, and who had eventually become mayor of Liverpool. Tarleton attended Oxford University with the intention of studying law but changed his mind sometime after the death of his father in 1773. At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, he purchased the rank of cornet in the British army. He participated in the failed Battle of Sullivan’s Island (28 June 1776), the first British attempt to take Charleston, and had been part of the patrol that captured General Charles Lee, Washington’s second-in-command, in December 1776. By 1780, Tarleton had achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel and was put in command of an elite unit of Loyalist fighters called the British Legion. Tarleton proved himself worthy of the command during the Siege of Charleston when he seized control of the Cooper River and helped trap Lincoln’s army in the city. Tarleton was still only 25 years old at the time.

Now, with Charleston under his control, Sir Henry Clinton wished to solidify British control of South Carolina, which would entail destroying the last elements of the Continental Army left in the state. Clinton sent his second-in-command, Lord Charles Cornwallis, in pursuit of Buford’s Virginians on 18 May. Buford, however, had had several days’ head start, and Cornwallis realized his foot soldiers would be unable to catch the Continentals before they could cross over into the safety of North Carolina. Cornwallis, therefore, handed the mission over to Colonel Tarleton, who was already well-known for his energy and speed. Realizing that this was his opportunity to make a name for himself, Tarleton gladly accepted the task and, on 27 May, departed from Cornwallis’ main army with 130 cavalry and 100 infantry of his British Legion, as well as 40 men from the 17th Dragoons. Despite the stifling summer heat, Tarleton and his men managed to cover 60 miles (96 km) in a single day, arriving at Camden, South Carolina, on the afternoon of the 28th.

Upon questioning the locals, Tarleton learned that Buford’s last known location was Rugeley’s Mill, only 12 miles (19 km) away. Tarleton also learned that John Rutledge, the Patriot governor of South Carolina, was accompanying Buford’s column. This delighted the young colonel, who was now faced with the prospect of capturing a traitorous governor as well as destroying a Continental regiment. He allowed his men to sleep for the rest of the day. At 2 a.m. on 29 May, he roused his exhausted troops, had them saddle up, and rode out of Camden. In all, Tarleton’s men would ride 105 miles (169 km) in less than 54 hours; many horses had been ridden to death, their dusty corpses left behind in Tarleton’s wake.

Preparations

By this point, Buford had made it to Waxhaws, a region straddling the border between North and South Carolina. He and his men had heard reports that the British were in close pursuit, leading Governor Rutledge to decide to part ways with the column and ride on ahead by himself; Buford also decided to send his baggage train and field guns ahead of his main column so that they would not fall into enemy hands. Buford and his men remained at Waxhaws to give the governor and the supplies time to make it into North Carolina. Buford had only just begun to get his column moving again when it was approached by a British officer on horseback, carrying a white flag of truce.

Buford halted his men and ordered them to form a battle line as he parleyed with the officer. The officer handed Buford a note written by Tarleton, in which the British colonel demanded the Americans’ immediate surrender; the offer, Tarleton coldly warned, would not be repeated. Buford could not have been blamed for considering the proposal, as most of his 380 men were raw recruits who had never before been in a battle; Tarleton’s troops, by contrast, were mostly elite Loyalist and British dragoons. Buford, however, refused to surrender. Once the British officer had ridden away to take his answer back to Tarleton, Buford surveyed his own battle line. The Virginians were drawn up in an open wood, positioned to the right of the main road and standing shoulder to shoulder in a single line of battle. The regimental colors were placed in the center of the line, a standard for all to see. To make his firepower as effective as possible, Buford ordered his men not to fire until the enemy came within the ‘killing distance’ of 10 yards (9 m).

Tarleton, meanwhile, formed his men up only 300 yards (274 m) away from the American line. This was close enough to taunt the Americans with their presence, but far enough to be outside of musket range. Upon surveying the American positions, Tarleton decided on a three-pronged attack. The first column of 60 British Legion dragoons and an equal number of mounted infantrymen would advance against the American left wing to “gall the enemy’s flank” (Boatner, 1173). At the same time, Tarleton himself would lead 30 selected dragoons against the American right flank, hoping to circle around and strike their rear. Tarleton’s third column, comprised of the remaining infantry and dragoons, would charge straight into the American center; it was hoped that the Virginians would become disorientated by this rapid onslaught and break under the pressure.

Battle of Waxhaws

At 3 p.m., Tarleton launched his attack. As the hooves of the British and Loyalist horses thundered toward the Patriot position, the Continentals held their fire; the British troopers could hear the Continental officers remind their men not to fire until they had come nearer. However, the Continentals were mostly raw recruits and lacked the discipline to carry out the order. As a result, the British horses were amongst the Virginians before most of them had had a chance to fire off their muskets. All three British columns soon slammed into the Patriot line; the sun flashed off the dragoons’ sabers as they were raised and lowered, hacking at the Continental soldiers below.

Tarleton’s victory at Waxhaws destroyed the last remnant of the Continental Army’s Southern Department.

After circling around to the Patriots’ rear, Tarleton noticed the regimental colors near the center of the line and charged straight for them. Tarleton allegedly cut off the arm of an American ensign who was trying to raise a white flag, before Tarleton’s own horse was shot out from under him. The British colonel was violently flung off his horse and onto the ground; since this took place at the center of the line, it was visible to almost everyone. The British and Loyalists believed that their colonel had been killed, which, according to Tarleton’s later report, accounts for what happened next. The British were filled with a “vindictive asperity” and, in an attempt to avenge their fallen colonel, began massacring the Patriot troops (Boatner, 1174). Those who tried to surrender were cut down where they stood, while all cries for quarter (or mercy) were ignored. One American eyewitness reported that, for 15 minutes after the battle had ended, the British “went over the ground plunging their bayonets into every [body] that exhibited any signs of life” (quoted in Boatner, 1174).

The Battle of Waxhaws was over within minutes. The Continentals had lost a staggering 113 killed and 203 wounded; of these wounded, 150 were so severely injured that the British could not carry them off and thereby left them on the battlefield to die. The British, by contrast, lost only 5 killed and 14 wounded. Tarleton, despite the spill from his horse, emerged from the battle unscathed. There remains a debate over whether a massacre actually took place; while Patriot survivors maintained that the Continentals were slain even after throwing down their weapons, some British and Loyalists denied that any troops had tried to surrender.

Aftermath & Legacy

Tarleton’s victory at Waxhaws destroyed the last remnant of the Continental Army’s Southern Department. The victorious Tarleton rejoined Cornwallis’ main army in time to participate in the Battle of Camden three months later. News of the ‘massacre’ at Waxhaws quickly spread throughout the Carolinas. Tarleton soon gained a reputation as a ruthless butcher; he was called ‘Bloody Ban’ by the Patriots, and the phrase ‘Tarleton’s Quarter’ was coined to refer to the mercilessness of British officers like Tarleton. The Patriots made great propaganda use of the battle, inspiring many Southerners to join the Patriot militias that were quickly sprouting up across the Carolinas.

Tarleton would never accept blame for the massacre. He would always claim that the slaughter took place after he had fallen from his horse and had lost control of his men. The Patriots, however, did not believe him or forgive him; after Cornwallis’ surrender at the Siege of Yorktown (28 September to 19 October 1781), Tarleton was the only British officer not invited to dine with the Continental officers. On the other hand, the British public praised Tarleton for his actions at Waxhaws. Unknown to the general public prior to the battle, Tarleton was praised in Britain as a war hero and was celebrated in his native Liverpool; the British public accepted the narrative that no massacre had been committed. In either case, Waxhaws served as a rallying cry for the South Carolinians in much the same way that the Battle of the Alamo would for the Texans over 50 years later. It galvanized resistance to British occupation in the South and helped the Patriots win this final phase of the war.

Editorial Review This article has been reviewed by our editorial team before publication to ensure accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards in accordance with our editorial policy.