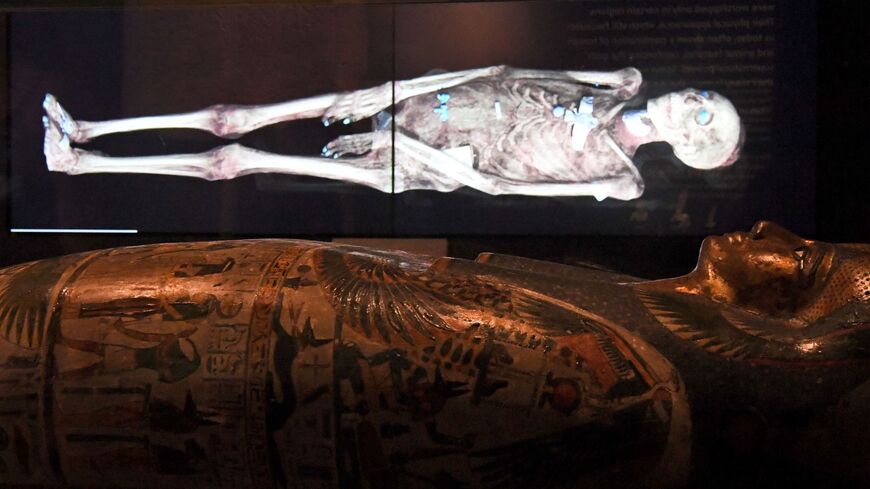

WARSAW, Poland — The scientists who discovered the first pregnant Egyptian mummy have now figured out how her unborn child was so well preserved after thousands of years. Researchers from the University of Warsaw say a strange process took place during the mother’s mummification that basically “pickled” the fetus — keeping its shape intact.

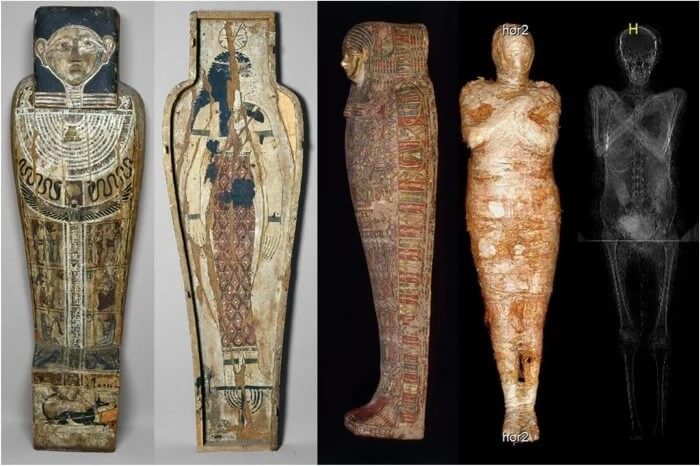

The fetus’s mother — called the “Mysterious Lady” — is the first recorded case of an Egyptian woman who was mummified while still carrying a child. Researchers believe the woman was between 20 and 30 years-old at the time of her death. The unborn child was approximately 26 to 30 weeks into its development.

After publishing their initial findings on the mummy in April 2021, the team is now revealing more about how the child’s body was able to survive the ancient mummifying process. It’s still a mystery, however, as to why the ancient Egyptians left the child inside the mother while removing her other organs.

“The fetus remained in the untouched uterus and began to, let say, ‘pickle’. It is not the most aesthetic comparison, but conveys the idea,” Egyptian archaeologist Wojciech Ejsmond and the researchers write in a media release.

Specifically, study authors say that blood pH in dead bodies drops dramatically and becomes more acidic. This includes the blood in the uterus. Over time, levels of ammonia and formic acid increase as well.

During the mummification process, Egyptians fill the body with natron, a naturally occurring sodium that dries the body out. This also limits the amount of air and oxygen in the corpse.

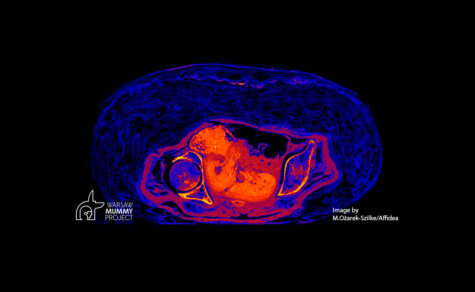

“The end result is an almost hermetically sealed uterus containing the fetus. The fetus was in an environment comparable to the one which preserves ancient bodies to our time in swamps,” researchers explain.

The fetus’s bones mineralized during mummification

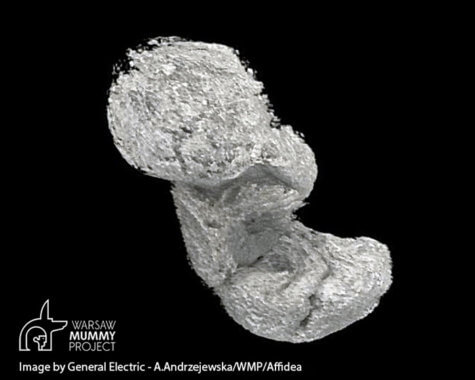

Ejsmond’s team adds that the change to an acidic environment in the womb led to the dissolving of the baby’s still-developing bones. The acid washed out key minerals which is important because mineralization is generally weak during the first two trimesters of pregnancy and speeds up later.

Researchers compared the process to dropping an egg into a pot full of acid. The eggshell dissolves, leaving only the albumen, the yolk, and the minerals from the shell behind in the acid. In this case, there are two different mummies (mother and child), which went through two different mummification processes.

For the fetus, researchers believe the baby dried up during the mother’s embalming. However, this led to the minerals from the child’s dissolved bones mineralizing around the soft tissues of the fetus and uterus. This is how scientists say they were able to detect the unborn child while taking CT scans of the Mysterious Lady.

Could there be more Egyptian babies in mummies?

Study authors believe potential fetuses in other mummies may not have well-preserved bones and therefore it’s even harder to spot them on X-rays or CT scans. While most radiologists are looking for bones in mummies, Ejsmond says this new study shows it’s also important to examine the shape of soft tissues in the pelvic area.

“The Mysterious Lady still keeps many secrets. We are still trying to explain why the fetus was left in the uterus while other internal organs were removed?” study authors write.

“Most importantly, there is a very high probability that there may be mummies of pregnant women in other museum collections. They may have not been sufficiently analyzed in this aspect. Now, considering our findings, it is only a matter of time before the next mummified pregnant woman is discovered.”

The findings are published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.