A team of researchers recently completed a study into the origins of two ancient skeletons from China that were both missing parts of their lower leg at the time they were buried. Based on extensive analysis of these human remains, the researchers concluded that the two individuals were aristocratic men who lived during the Eastern Zhou dynasty (771—256 BC), or to be more precise approximately 2,500 years ago. Most astonishingly, the study authors are virtually certain that the men had parts of their legs amputated as punishment for some kind of illegal or unethical deeds, after which they were allowed to live out their lives in freedom and comfort.

While this might sound like a bizarre theory, in fact Chinese authorities during the Eastern Zhou years did prescribe amputation as a form of punishment. This practice of legalized mutilation, which was known as “yue,” originated in ancient China during the days of the Xia dynasty (2,100—1,600 BC), and endured for two millennia before finally being outlawed by the Han dynasty in the second century BC.

“Such discoveries, along with some previous findings, reflect the cruelty of the penal system in early China,” lead study author Qian Wang, a professor of biomedical sciences at the Texas A&M University School of Dentistry, told Live Science.

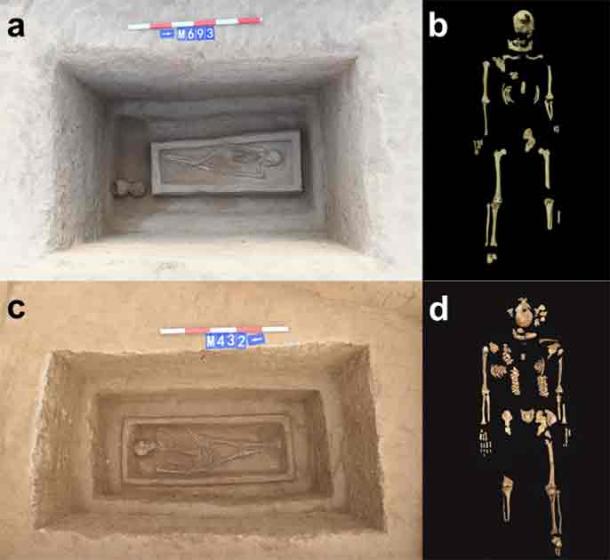

The two burials and the amputated skeletons found within them. (Wang, Q. et al/Archaeological & Anthropological Sciences)

Punitive Amputation: Harsh Justice in Harsh Times

The skeletons of the two men were excavated from an ancient burial site in east central China’s Henan Province. Each was found inside a fancy coffin built in two layers, which were arranged so they were facing north and south (a practice reserved for individuals who were of high social status, according to the researchers). They were buried with an assortment of grave goods, some of which were valuable, including pottery, stone tablets and copper belt hooks.

To learn more about who these individuals were and what exactly they had experienced, the researchers utilized various methodologies of high-tech analysis, including computed tomography (CT) scans and radiocarbon dating procedures, to analyze their bones.

Using this approach, the scientists discovered that the skeletons belonged to two middle-aged men, approximately 40 and 50 years old respectively, who lived under Eastern Zhou rule around 550 BC. A chemical analysis of the elements found in their bones revealed that each man had consumed a diet high in both proteins and beneficial plant nutrients. This was significant, because it means the men’s diets matched what was normal among the Eastern Zhou aristocratic class.

Each of the skeletons was missing the lower section of one of their legs, with one having suffered an amputation of the left leg and the other of the right. The ends of the lower-leg bones (tibia and fibula) had healed evenly and completely, and neither amputation seemed to have been done in a rapid or haphazard manner. The quality of the amputation revealed surgical skill, and the care the men received after the procedure was completed was good enough to prevent infection or any other type of complication.

Taken altogether, the findings of the original excavations and the subsequent analysis proved these were men of high social status who experienced no diminution of that status following the amputation of their lower legs.

In an article about their study published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, the scientists explained how they had determined that the men had been sentenced to “punitive amputation for felonies.” They noted that the “bioarchaeological evidence corroborated with historic written records of law and punishment from the penal system of the Zhou Dynasty,” while also highlighting the fact that “the individuals were allowed to recover, and they continued to live for years.”

The researchers were able to rule out the possibility that the amputations were related to some type of severe traumatic injury or illness, or that the men had been born missing parts of their limbs. They also rejected the possibility of sacrificial amputation, since this practice has never been mentioned in the historical records from Zhou dynasty times.

The Strange Nature of “Elite Privilege” in Eastern Zhou China

The ancient Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi commented on the Zhou penal system in some of his writings. He claimed that the highest-ranking military officers and aristocrats closely connected to royalty were exempt from more extreme punishments, like amputation. He also wrote that these individuals had the right to be buried in the finest coffins, which were constructed in three layers.

Based on these important facts, the researchers deduced that the two individuals excavated from the cemetery in Henan must have been relatively low-ranking officers or administrators. This would have made them subject to amputation if their misdeeds were judged as being serious enough, despite their elite identities.

According to Qian Wang, the Zhou legal code prescribed amputation as a suitable punishment for many types of felonies, including stealing, neglecting duties, and lying to the monarch, to name a few. It seems amputation could sometimes be prescribed as a more merciful punishment, for influential people accused of crimes that might have brought the death penalty or long-term imprisonment for individuals of a humbler social status.

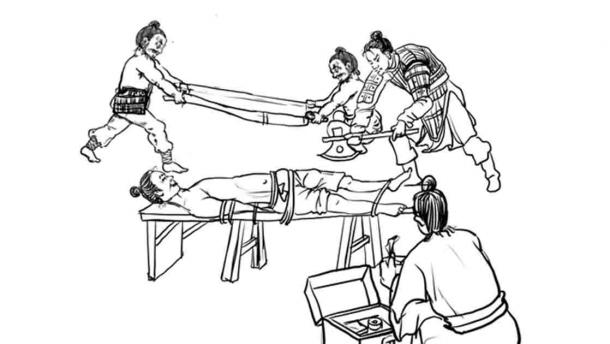

A hypothetical recreation of yue, with a doctor waiting nearby. (Qian Wang et al. Archaeological & Anthropological Sciences)

Incredible as it may sound, it would appear that being subject to punitive amputation during China’s Eastern Zhou times could be seen as an example of “elite privilege” in action, at least in some circumstances.

One Culture’s Barbarity is Another’s Fair Punishment

While such a punishment would be judged barbaric by modern standards, it seems it was not viewed that way in the Zhou culture that dominated much of China during the first millennium BC. Among the ancient Chinese, amputation was used as a replacement for prison, not as torture or as an extra indignity.

Whatever the actual crimes were that the individuals committed, it is clear that they received high-quality medical care after the amputation procedures were completed, and did not face additional sanctions beyond this radical procedure. In the words of the researchers, “these cases enrich our understanding of the physical consequences of lower limb amputation and illuminate the social context of amputation during ancient times.”

Top image: A Chinese prisoner who has tried to escape is lying on the ground while a man wearing a red jacket is cutting his ankles with a sword. Colored stipple print by J. Dadley, 1801. Source: Wellcome Collection/ Public Domain