According to philosopher Cicero (106 – 43 BC), from the beginning of the Roman Republic (509 – 27 BC), priests (pontifex maximus) recorded important events that occurred during the year – like a calendar. form of chronicles called Annales Maximi – on a whiteboard and placed in a public place for the public to see.

This work was carried out regularly until 131 BC, when it stopped, and for some reason that even Cicero did not know. From then on, responsibility for chronicling passed to scholars such as Cato (95 – 46 BC).

Although not complete, Acta diurna took on many forms of journalism later on.

Besides gossip and word of mouth, the Romans at that time did not have any official information channels to grasp the events taking place in the territory. So in 59 BC, Julius Caesar (100 – 44 BC) decided there needed to be a form of daily newsletter to fill the gap. He published the minutes of meetings at the Senate (Senate) on the same type of whiteboard (called an album) that was used to copy chronicles like in the past and placed it in public places, such as the Roman Forum. (Forum Romanum) for the public to follow. After gaining almost absolute power in 45 BC, Caesar stipulated that all documents would remember and publicize the events in the Senate, in addition to the behavior of the people. This chronicle is called Acta diurna (literally, daily events) and bears many of the features of later journalism, although not completely. Its content includes the affairs of the Senate, the names of consuls and magistrates, and many other information about crimes, newly built buildings, and the state of affairs. births, marriages, divorces, obituaries, festivals, games, grain suppliers,… or even military activities.

‘Roman Fish Market’ painting under the Octavius arch, one of the public places where Acta Diurna is posted.

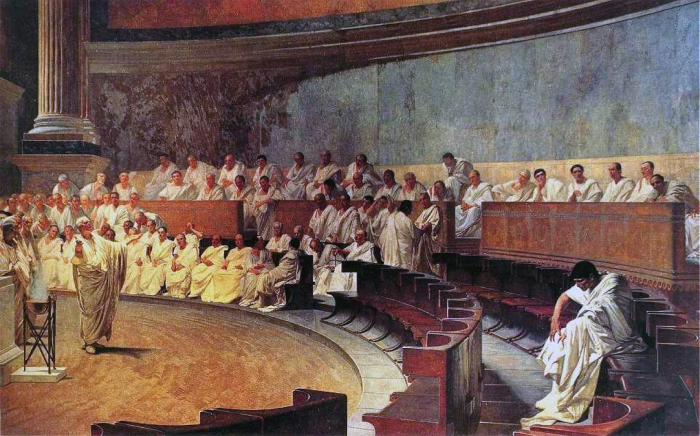

Acta diurna is published fairly regularly although not every day. Later scribes made many copies of it, added additional information, and sent it around. After Caesar died of assassination, this work was still maintained by Augustus (63 BC – 14 AD) – the first emperor of the Roman Empire (27 BC – 395 AD) – because he noticed it. Useful as a propaganda and orientation tool. However, Augustus removed the content about the Senate and replaced it with information and images about military achievements (like the motifs on the triumphal arches).

In the book Satyricon, the scholar Petronius (AD 27 – 66) and also a minister of the time of Nero (AD 37 – 68) composed a parody of Acta diurna with news like: “July 26, 30 boys and 40 girls were born at the Cumae estate; 40,000 bushels of wheat were moved from the threshing floor into the warehouse; 500 oxen were yoked around their necks; the slave from Mithridates was crucified for defaming Sir Gaius; 10 million sesterces (Roman money) were confiscated from the treasury; A fire broke out in the Pompey Garden, possibly starting from the house of the foreman Nasta,…”

The painting ‘Cicero unmasks Catiline’ (1889) painted by Cesare Maccari, shows an activity of the Senate. The acta diurna would announce important events to the Roman people, such as the outcome of a trial.

The natural philosopher Pliny (AD 23 – 79) recounted some of the content he read in Acta diurna such as the story of a dog’s loyalty, the quarrel between two families at a funeral, or a trial at a court,… Historian and statesman Cassius Dio (155 – 235) also collected the story of a talented architect who saved the whole village from the risk of collapse. , but this person’s name was forbidden to be published by Emperor Tiberius (42 BC – 37 AD) (possibly due to jealousy). While the Stoic philosopher Seneca (4 BC – 65 AD), who was also a statesman, complained that the Acta diurna recorded too many divorces, …

The publication of Acta diurna was probably maintained until 235 AD, or even longer – before the capital was moved to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) during the Byzantine period (330 AD). But the unfortunate thing is that no one has kept any original fragments from Acta diurna, whose content is only mentioned through the works of historians Tacitus (56 – 120 AD) or Suetonius (69 – 122 AD), … However, one thing is certain: below the foot of the news or announcements in Acta diurna are the words publicare et propagare (publicity and dissemination) – implicitly referring to everyone, whether Roman citizens or not. , must have the responsibility to publicize and disseminate them.