Impressionism was an art movement which began in Paris in the last quarter of the 19th century. The impressionists tried to capture the momentary effects of light on colours and forms, often painting outdoors. They frequently used bright colours with a thick application to capture landscapes and contemporary everyday life in cafés, the theatre, and the boulevards of Paris.

The Term ‘Impressionism’

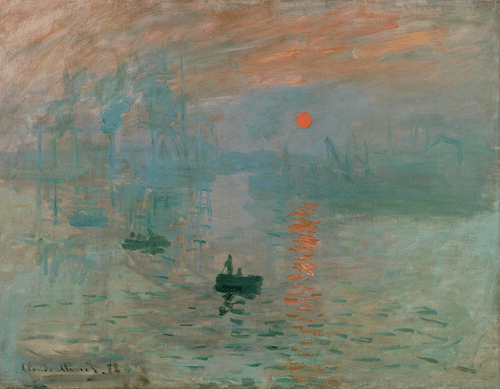

The term ‘impressionism’ is a useful but ambiguous label, which can be applied to a group of artists from the 1860s who were painting in France, particularly in Paris. It was coined by the critic Louis Leroy after seeing a work by Claude Monet (1840-1926) at the First Impressionist Exhibition in Paris in April 1874. The painting was titled Impression, Sunrise and shows a view of Le Havre’s industrial harbour with a fierce orange sun reflected in purple waters. Leroy and other critics then applied the term ‘impressionism’ to many of the works on display which had vague forms and very obvious brushstrokes.

Impressionism involved a new approach to the colours being used & the subjects.

In the beginning, then, the term ‘impressionism’ was a derogatory one used by some conservative art critics to ridicule this new art style. However, the artists involved (or most of them) soon adopted the term to describe themselves and their independent exhibitions, even if nobody could quite agree what the term meant precisely. ‘Impressionism’ remains a useful general label, and it does certainly capture the essential thing these artists were trying to paint, that is the momentary effects of light and colours rather than precise, photographic-like reproductions of reality (photographs had become popular from the 1820s). They were trying to create an impression of reality, or more precisely, their individual impression of the reality they saw.

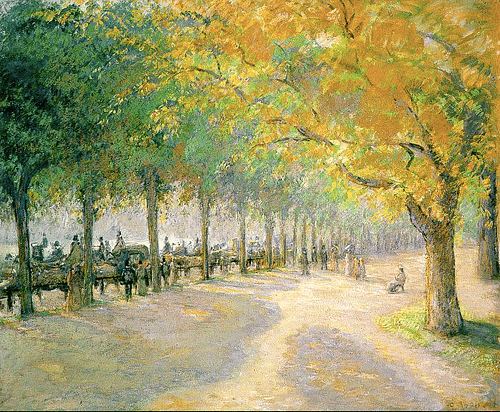

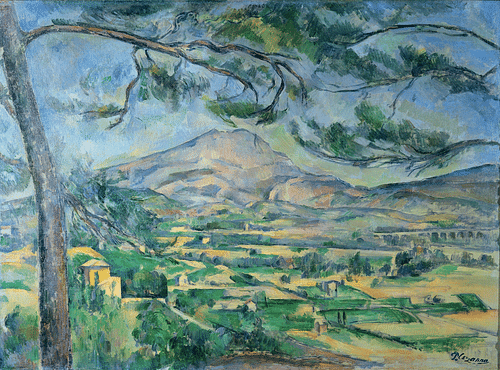

‘Impressionism’ as a term does have its limitations. Just exactly when, what style, and who the term may be applied to is much debated by art scholars. The artists who have been called impressionists were often quite different. Painters like Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Edouard Manet (1832-83), and Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1896), for example, were often interested in form and composition and in using less visible brushstrokes. This is in contrast to the hazy effects produced by artists like Monet, Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), and Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). All of the artists could paint in the traditional manner as shown by their earlier works, but some were definitely more ‘impressionistic’ than others.

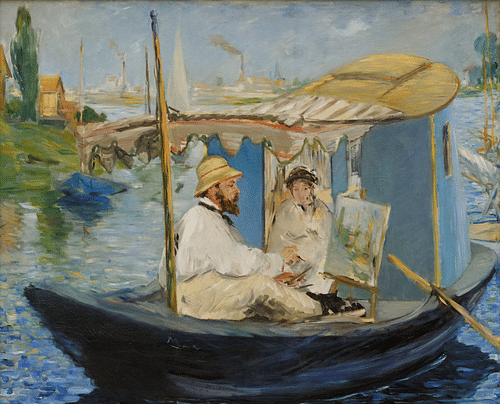

To further complicate the use of the term, impressionism also involved a new approach to the colours being used and the subjects. The brighter palettes often used were very different from traditional painting but, on the other hand, some impressionist artists deliberately used more subdued tones. The use of purer colours was another feature. The impressionists stood out for their interest in capturing daily life, the poorer classes, and landscapes, but again, this was not always the case. Finally, an important element of the process of producing a painting for many impressionists was to paint the subject outdoors (en plein air), now a possibility thanks to the invention of portable tin tubes with a screw cap containing readymade paint (previously, artists had to grind their own pigments). But yet again, some artists preferred to continue working only in their studios, and even the die-hard en plein air proponents still added finishing touches to their canvases back in the studio. In short, ‘impressionism’ has come to mean the art produced from the 1860s to the end of the 19th century which challenged the conventions of traditional fine art, challenges which were made by different artists in different ways.

The Impressionist Style

The distinct elements of the impressionist style may be summarised as:

- An interest in capturing the fleeting effects of light and colour on a particular subject.

- A brighter and wider range of colours than had been used previously.

- Using obvious brushstrokes of various shapes as an effect in themselves.

- An innovative framing of a subject, often abruptly cutting off figures and architecture.

- An innovative treatment of perspective, often deliberately misrepresenting reality.

- A focus on contemporary everyday life and people of all classes as opposed to mythological and religious themes.

- Painting outdoors to better capture rapidly-changing light conditions.

Not all of these features may be present in the same work of art.

Just like any other art style, impressionism did not spring from thin air. Impressionist artists were inspired by certain of their fine art predecessors like William Turner (1775-1851) for his vague forms, Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) for his use of bright colours, and Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) for his unusually thick application of paint.

The impressionists amalgamated these various ideas in a single technique and also inspired each other, encouraging friends in the group to try different methods, subjects, and palettes. There were frequent spells where two or more artists worked together, even painting the same scene at the same time, as happened on several occasions with Renoir and Monet or Cézanne and Pissarro. Most of the artists changed their own style over their careers, too. Pissarro had a stab at pointillism (see below), Degas became interested in alternative perspectives, Caillebotte abandoned his smooth brushstrokes for a period, and Cézanne’s work became ever more abstract and his forms more geometrical as he grew older. Monet certainly became the most famous impressionist in his own lifetime, but Cézanne once commented that Pissarro was “the first impressionist” (Shikes, 78). It is difficult, then, to say who started the impressionist style as in reality, it evolved in the works of several painters at the same time. In addition, there were, of course, artists outside France similarly experimenting with new approaches to art.

The Impressionists

What we now call the first impressionists were a group of like-minded avant-garde artists who frequented the same cafés and restaurants in Paris. New members, including non-French painters, came in via friendships and so the group grew over time. Many of the artists also moved around to find new inspiration in such places as the south of France or Brittany. The group included two women artists, Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), in a period when such a career choice was highly unconventional.

Most of the impressionists had studied art in conventional schools under respected artists, but they broke away from the rules their tutors had told them to stick to. Determined to get their innovative work shown outside the one outlet for fine art, the conservative Paris Salon, they organised the Paris impressionist exhibitions, 1874-86. These shows irked a good number of art critics and did not bring many sales, but at least the impressionists got noticed. Some of the artists like Degas and Caillebotte had an independent income, but others like Monet and Renoir were obliged to make money from their art or literally not have food to eat (or paint in still lifes). Fortunately, the wealthier artists frequently helped out the poorer ones, buying their paintings and even paying their rents on occasion. There were, too, a small number of collectors like Victor Chocquet (1821-1891) and Dr. Paul Gachet (1828-1909) who had the vision to see that these works had a tremendous cultural value, if not right then, at least at some point in the future. And how right they were. It is one of the great ironies of impressionist art that the paintings which today sell for tens of millions of dollars were often created by artists who could not even afford the paints and canvas to realise their visions.

The Neo-Impressionists

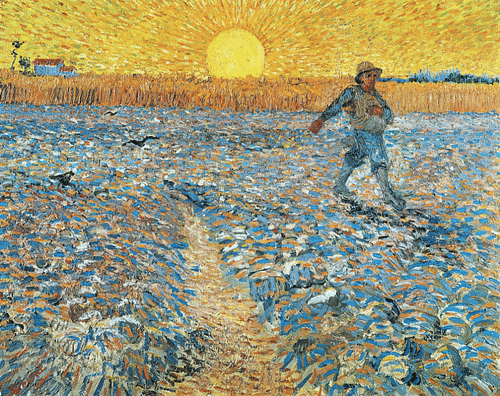

Just as the impressionists had challenged the conventions of traditional art, so, too, a younger generation of artists came along which challenged the conventions of impressionism. First, artists like Georges Seurat (1859-1891) and Paul Signac (1863-1935) developed pointillism, where paint was applied in small dots and according to scientific theories of colour spectrums and light effects. Then, from the mid-1880s, artists like Vincent van Gogh (1853-90) and Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) became even more daring in their use of colours. They deliberately used contrasting but complementary colours (e.g. blue and yellow or red and green) and bold black outlines for dramatic effect. They used the ‘wrong’ colours in the ‘wrong’ places, deliberately showing the viewer what they could not see in reality (e.g. a vermilion sky or green skin). Another feature of the neo-impressionists was the use of symbols in their works to provoke an emotional reaction from the viewer. Paintings were becoming more complex in terms of how they could be interpreted and understood. This idea would be stretched even further in the 20th century by such artists as Henri Matisse (1869-1954) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) so that art became not merely a matter of bending or breaking established conventions but abandoning them altogether.

Editorial Review This article has been reviewed by our editorial team before publication to ensure accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards in accordance with our editorial policy.